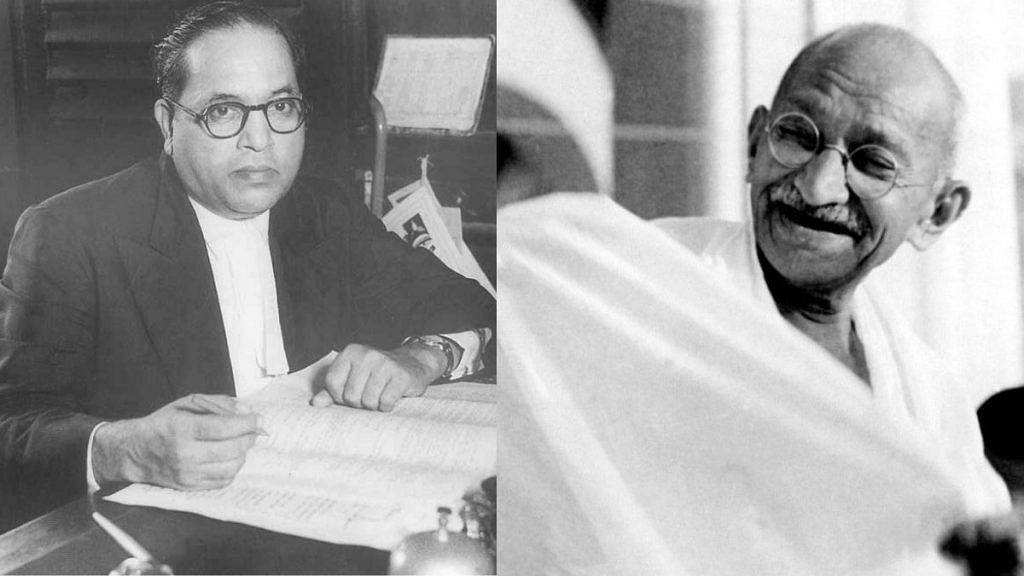

At the Round Table Conference [in London], Gandhi and Ambedkar clashed, both claiming that they were the real representatives of the Untouchables.

The conference went on for weeks. Gandhi eventually agreed to separate electorates for Muslims and Sikhs, but would not countenance Ambedkar’s argument for a separate electorate for Untouchables. He resorted to his usual rhetoric: ‘I would far rather that Hinduism died than that Untouchability lived.’

Gandhi refused to acknowledge that Ambedkar had the right to represent Untouchables. Ambedkar would not back down either. Nor was there a call for him to. Untouchable groups from across India, including Mangoo Ram of the Ad Dharm movement, sent telegrams in support of Ambedkar.

Eventually Gandhi said, ‘Those who speak of the political rights of Untouchables do not know their India, do not know how Indian society is today constructed, and therefore I want to say with all the emphasis that I can command that if I was the only person to resist this thing I would resist it with my life.’

Having delivered his threat, Gandhi took the boat back to India. On the way, he dropped in on Mussolini in Rome and was extremely impressed by him and his ‘care of the poor, his opposition to super-urbanisation, his efforts to bring about co-ordination between capital and labour’.

Also read: Ambedkar was wrong, Gandhi wrote against untouchability in Gujarati journals too

A year later, Ramsay MacDonald announced the British government’s decision on the Communal Question. It awarded the Untouchables a separate electorate for a period of twenty years. At the time, Gandhi was serving a sentence in Yerawada Central Jail in Poona. From prison, he announced that unless the provision of separate electorates for Untouchables was revoked, he would fast to death.

He waited for a month. When he did not get his way, Gandhi began his fast from prison. This fast was completely against his own maxims of satyagraha. It was barefaced blackmail, nothing less manipulative than the threat of committing public suicide. The British government said it would revoke the provision only if the Untouchables agreed. The country spun like a top. Public statements were issued, petitions signed, prayers offered, meetings held, appeals made.

It was a preposterous situation: privileged caste Hindus, who segregated themselves from Untouchables in every possible way, who deemed them unworthy of human association, who shunned their very touch, who wanted separate food, water, schools, roads, temples and wells, now said that India would be balkanized if Untouchables had a separate electorate. And Gandhi, who believed so fervently and so vocally in the system that upheld that separation, was starving himself to death to deny Untouchables a separate electorate.

The gist of it was that the caste Hindus wanted the power to close the door on Untouchables, but on no account could Untouchables be given the power to close the door on themselves. The masters knew that choice was power.

As the frenzy mounted, Ambedkar became the villain, the traitor, the man who wanted to dissever India, the man who was trying to kill Gandhi. Political heavyweights of the garam dal (militants) as well as the naram dal (moderates), including Tagore, Nehru and C. Rajagopalachari, weighed in on Gandhi’s side. To placate Gandhi, privileged-caste Hindus made a show of sharing food on the streets with Untouchables, and many Hindu temples were thrown open to them, albeit temporarily. Behind those gestures of accommodation, a wall of tension built up too. Several Untouchable leaders feared that Ambedkar would be held responsible if Gandhi succumbed to his fast, and this in turn, could put the lives of ordinary Untouchables in danger. One of them was M.C. Rajah, the Untouchable leader from Madras, who, according to an eyewitness account of the events, said:

“For thousands of years we had been treated as Untouchables, downtrodden, insulted, despised. The Mahatma is staking his life for our sake, and if he dies, for the next thousands of years we shall be where we have been, if not worse. There will be such a strong feeling against us that we brought about his death, that the mind of the whole Hindu community and the whole civilised community will kick us downstairs further still. I am not going to stand by you any longer. I will join the conference and find a solution and I will part company from you.”

Also read: 17th Lok Sabha looks set to confirm Ambedkar’s fears: no vocal Dalits in Parliament

What could Ambedkar do? He tried to hold out with his usual arsenal of logic and reason, but the situation was way beyond all that. He didn’t stand a chance. After four days of the fast, on 24 September 1932, Ambedkar visited Gandhi in Yerawada prison and signed the Poona Pact. The next day in Bombay he made a public speech in which he was uncharacteristically gracious about Gandhi: ‘I was astounded to see that the man who held such divergent views from mine at the Round Table Conference came immediately to my rescue and not to the rescue of the other side.’ Later, though, having recovered from the trauma, Ambedkar wrote:

There was nothing noble in the fast. It was a foul and filthy act . . . [I]t was the worst form of coercion against a helpless people to give up the constitutional safeguards of which they had become possessed under the Prime Minister’s Award and agree to live on the mercy of the Hindus. It was a vile and wicked act. How can the Untouchables regard such a man as honest and sincere?

According to the Pact, instead of separate electorates, the Untouchables would have reserved seats in general constituencies. The number of seats they were allotted in the provincial legislatures increased (from seventy-eight to 148), but the candidates, because they would now have to be acceptable to their privileged caste–dominated constituencies, lost their teeth. Uncle Tom won the day. Gandhi saw to it that leadership remained in the hands of the privileged castes.