Samir Bordoloi is an unusual Assamese. He left a flourishing job with Tata Chemicals for his first love—farming. Armed with a degree in agriculture from the Assam Agricultural University, he became a ‘plant doctor’, visiting farmers with dollops of advice to switch to organic farming. In the first year itself, he managed to link 1,500 farmers to his clinic in Jorhat, with a modest annual subscription of Rs 50. He started providing organic inputs to the farm gate. A turning point in his approach occurred when he got a chance visitor—Peggy, an organic aficionado. He accompanied her to Majuli, the world’s largest river island. A quiet conversation made him ponder why he was doing a hard sell for expensive organic manure, instead of chemical fertilizers. Zero-input agriculture with a self-sustaining model would be the way forward. He travelled to Nagaland, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh to understand indigenous farm technologies of tribal farmers who had no recourse to cow dung. Herbs and extracts of weeds served as substitutes. He used this approach to revive two farms near Dibrugarh with farmers who had earlier enrolled in the old ULFA camps, lured by dreams of an elusive green revolution. Deeply affected during Operation Bajrang and Rhino by the army, they were desperate for a renewal of their farms. Bordoloi also saw young people shying away from agriculture, which became his next area of focus. He started a programme, Parivartan, with 300 schoolchildren in Jorhat, teaching them vermicomposting and organic farming. Young change agents forced their parents to change. Subsequently, he acquired 4 bighas of land next to Lahowal College near Dibrugarh, primarily targeting rural students. He set up an organic farm along with a bamboo house, and started living there. He offered weekly classes for undergraduate students, subsequently enrolling them as interns. Word spread fast. A big industrialist wanting to foray into organic farming made Bordoloi a partner. The largest organic farm in the Northeast, spread over 8 hectares in an industrial area, with 250 cows and a 300 MT vermicompost unit, thus came into being. Bordoloi now got a real chance to put his learning to practice. He then acquired 30 bighas of land near Guwahati to start a learning centre.

According to Bordoloi, there is a ‘conspiracy behind food’ unleashed by the multinational corporations who sell hybrid seed varieties, decimating local gene pool and crops. He started targeting low-volume high-value crops, modelled on the ULFA camps. He enrols ‘green commandos’ for a paid three-day training programme. ‘Glamorizing farming’ with the military outfit of commandos, it became an instant hit. Currently, 426 commandos are spread across Meghalaya, Sikkim, Manipur, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh. The ‘Farm Connect’ programme made him open a store in Guwahati. Urban commandos became a link between farmers and consumers, encouraging people to adopt a farmer. In a win-win proposition, they got organic food at lower price, while the farmer secured higher rates. Digital platforms like Facebook and Instagram are extensively used for targeted outreach. Now, he is expanding into farm plus activities: an organic restaurant and agro-tourism.24 In recognition of his achievements, he secured the Ashoka Fellowship in 2019 and has bagged several national and state awards. Bordoloi’s organization, Society for Promotion of Rural Economy & Agricultural Development, North East (SPREAD-NE), is a pioneering example of private agricultural extension, enlisting youth in agriculture while promoting organic practices.

The Central Agricultural University, Imphal, has seven affiliated colleges in the Northeast and six vocational training centres in the region. Its Vice Chancellor, Dr Premjit Singh, feels that the approach of government departments is ‘different’, implying a lack of interest in collaboration with academia. Research institutes independently develop rural farm technologies, seed varieties and have an outreach through NGOs. In 2017, they distributed more than 1,00,000 plants to 10,000 families across the region. In his personal capacity, he is also an advisor to the Bhartiya Kisan Sangh, an affiliate of the RSS. He is engaging 5,000 farmers, affiliated with the organization, to establish twenty model fruit villages across the Northeast.

Despite these tremendous gains, the Northeast is yet to transcend the bounds of geography. Sporadic efforts by individual farmers and the FPC are unable to break the glass ceiling. Dr K.M. Bujarbaruah, a well-respected scientist and a former VC of the Assam Agricultural University, feels that a consortium approach to marketing must be adopted. ‘Let us say there is a demand for 100 MT organic turmeric. It will be difficult to immediately source good quality turmeric in large quantities.’ He argues that states like Arunachal Pradesh have such a low intensity of chemical fertilizer usage that they can easily switch to organic farming. Mizoram and Sikkim have tapped the growing organic market. ‘The bio-resources of the Northeast, which include below-the-ground resources, are unique in the country. Bacteria and fungi found in these parts, through genetic manipulation, can transform bio-resource to bio-wealth,’ he adds. The states of the Northeast should focus on those crops in which they have a comparative advantage, rather than trying multiple small experiments all over. ‘Speciality horticulture’ will provide economies of scale and help convert the region into a single market, he says. Medicinal plants found in the Northeast have a strong demand in pharmaceutical companies, but a strong documentation of resources is essential. Bujarbaruah believes that for farmers of the Northeast, digital platforms like the Electronic-National Agricultural Market (E-NAM), initiated by the Central government, provide a useful medium to reach remote customers and secure remunerative prices. His long experience in the region has seen mixed gains. The real value, Bujarbaruah feels, will be realized once agro-processing takes off in the Northeast, which hasn’t happened so far. A unified market within the region is a starting point.

The organic revolution of the Northeast is one of the least known facets of the region. As the prolonged impact of the Covid-19 pandemic makes people wiser to the importance of healthy living and healthy eating, the farm practices of the region could serve as an inspiring model for others to emulate.

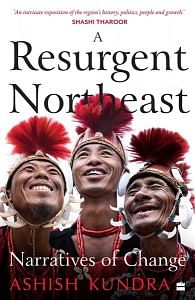

This excerpt from Ashish Kundra’s A Resurgent Northeast has been published with permission from Harper Collins.

This excerpt from Ashish Kundra’s A Resurgent Northeast has been published with permission from Harper Collins.