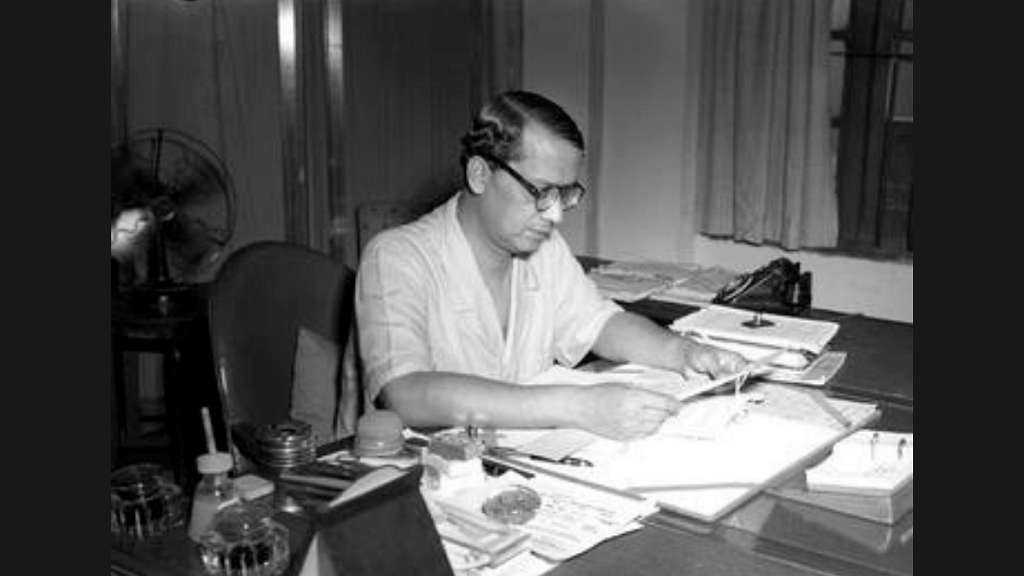

The first CEC Sukumar Sen remains one of the unsung heroes in the history of elections in India. He left no memoirs but only a few personal papers. The ECI, the organisation that he was able to create, and the elections that he delivered in a short span of time, were nothing short of a miracle. Nehru was giving him barely one year to get organised. Sen demanded both time and patience.

Ramachandra Guha has described him as ‘the man who had to make the election possible, a man who is an unsung hero of Indian democracy’. He had the guts to tell the prime minister to wait. For, no other officer of the State, certainly no Indian official has ever had such a stupendous task placed in front of him. Perhaps, his greatest achievement was that he had devised the processes that made the first elections possible without too many glitches, setting the tone for all the elections that followed.

First of all, there was the size of the electorate—17 crore 60 lakh Indians aged 21 or more, compounded by the fact that about 85 per cent of them could not read or write. Each one had to be identified, named and registered. The registration of voters was merely the first step. How did one design party symbols, ballot papers and ballot boxes for a mostly unlettered electorate? Then, sites for polling stations had to be identified, and honest and efficient polling officers were to be recruited.

Moreover, concurrent with the general elections would be elections to the state assemblies. Working with him in this regard were the election commissioners of the different provinces, also usually ICS men. Born in 1899, he was educated at the Presidency College, Kolkata, and London University, where he was awarded a gold medal in Mathematics. He joined the ICS and served in various districts and as a judge before being appointed the Chief Secretary of West Bengal, from where he was sent on deputation as the CEC. The then chief minister of West Bengal, Dr B.C. Roy, recommended his name to the prime minister.

Instead of serving in the executive, he had to spend considerable 19 years in the judiciary as he must have been considered to be a man of unbending attitude. He served only the customary innings in the districts before being seconded to the judiciary by the British Raj. There is no record to show that Sukumar Sen failed in riding in the ICS examination.2 His daughters told Navin Chawla that their father was a fair and just man, quite grounded and not at all ‘imperial’, though he was a member of the ICS. ‘My father was not a favourite of the British,’ recalled Janyanti, the eldest daughter. ‘He listened to all but took a decision after listening to all sides. As a judge, he was known to be fair, and often ruled against what might have been viewed as “imperial” interests’. She felt that this may also have been the reason why the British government retained him on the judicial side; they were

‘wary’ of bringing him into the executive.

Also read: 70 yrs ago, UP & Punjab went to polls in free India’s 1st election. Here’s what it was like

In ‘Reminiscences of a Civil Servant’, a speech to civil servants in Calcutta, Sen said: We had perforce to be tolerated in the service [by the British government]. But authority saw to it that none of the plums of office came to us. There was quite naked discrimination against those of us in particular [who were] believed to entertain nationalistic sympathies. We the ‘suspects’ in the service were deliberately kept out of the executive branch. Indeed, as a judge, I was always able to follow the dictates of my conscience. That he brought to August 1947 the resilience that made him Chief Secretary to the very difficult government

of West Bengal was due undoubtedly to the fact that he had much more than steel in his frame. Bengal in the war years was almost a lost province and, when division rent it, what seemed to be wholly ripped off was the morale of the administration.

The reign of Sukumar Sen as the Chief Secretary for three years, on the other hand, seemed to prepare him for the most unconventional job that ever came to an ICS man. He was chosen to play obstetrician and deliver Indian democracy’s first crop of about 3,000

elected representatives. Realising with surprising un-ICS humility that democracy likes its mechanics to be as self-effacing as possible, the CEC became an unseen, unbiased builder, patiently judicial in his attitude to parties but insistent in regard to the machine

he tended.

Yet so well did Sukumar Sen pull it off that, in February 1987, Shankar’s Weekly article stated under the heading ‘The Man of the Week’: “After the first Indian general elections, our Chief Election Commissioner was asked to supervise elections in the newly independent country of Sudan. He spent nine months in that country, setting up the infrastructure for polling and making sure it worked. It was Sukumar Sen who had devised the system of identifying parties by different symbols and colours—this method was now adapted to the

Sudanese voter, who, like his Indian counterpart, was mostly illiterate. On the 14th of December 1953, after the elections were completed, Sen spoke on Sudanese radio of this ‘very happy chapter of my life’. He exhorted the people to trust their politicians, who, he said, were all ‘wise and patriotic’; in Government or in the Opposition, ‘you will find them all working for the ultimate good of the country’. But he warned them that in view of Sudan’s underdevelopment they would ‘have to work very very hard for many long years’ to nurture the plant they, and he, had sown. Still, he hoped that their experiment in free

elections would be ‘an example and a source of inspiration to the Arab and the African world’. Sen’s work in the Sudan was the subject of a stirring tribute in the Egyptian newspaper, Al Misri. In its issue of 18th December 1953, it called the Indian ‘one of those men who were born to lead the pitched battles for Democracy’. It condemned the cynicism

of British officials and the British press, which had a priori dismissed the elections as a farce. For under Sen’s supervision the Sudanese polls had been ‘free in every sense of the word’. Indeed, the singular lesson of their success was that ‘the age in which the politicians of the British Empire used to think that they are issuing orders, is finished’.

Also read: Guha on ‘harmoniser’ Gandhi, Lavasa calls India’s first elections ‘fateful experiment’

But, largely due to Sukumar Sen, it can be said that apart from Panchshila the most impressive gift we have given to Asia in the first decade of our freedom is the system of elections that has been perfected in this country. His success was recognised internationally when he was asked to organise the first Sudan elections. As the voters get ready to clutch the voting papers for the second Indian general elections, every political party has a reason

to remember Sukumar Sen with gratitude for doing a very difficult job very well indeed.

A grateful government rewarded Sen the Padma Bhushan in 1954 in the first batch of Civilian awards. His younger daughter said that her father was a doer and not a talker. He was, therefore, in the saddle when he died at the comparatively young age of 63. Ramachandra Guha has described Sen in A Forgotten Bengali Hero as the man who had to make the election possible, a man who is an unsung hero of Indian democracy.