Originally founded as an Anglo-Indian orphanage in 1864, St Mary’s was a cosmopolitan place where diverse classes and castes, religions and regions, ethnicities and races were represented. There were paupers and princes, Catholics and Protestants, Syrian Christians and Latins, Jews and gentiles, Malabaris and Goans, East Indians and Anglo-Indians from all the regions of the subcontinent and beyond. Indeed after the cotton boom during the American Civil War in the 1860s, Bombay was one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world as the variety of head dresses seen at the Cotton Exchange demonstrated.

If Bombay was a microcosm of post-Partition India, St Mary’s was a microcosm of the city. We were taught to value diversity as enriching, not diminishing. Here we made lifelong friends, forged loyalties that reached across seas and continents. We were three musketeers that hung together through thick and thin: Moses Taghioff, a Baghdadi Jew; Munawar Baig, a Konkani Muslim; and I, a Goan Christian. The Jesuits I encountered there were my role models. They made the greatest impact on me not just when they taught in class but more so when they mixed with us on the playgrounds. This is where my journeying with the Jesuits began and now it has come full circle as I write these lines at Arrupe Niwas, lodged on the premises of the St Mary’s campus. It is residence for those among us who need assisted care.

Many years later when I was in vanvas—exiled to the concrete jungle in Delhi—I wrote an elegy for the Bombay I grew up in, and what living there meant: Mumbai Meri Jaan, Meri Rozi Roti, Meri Jivan Dharti Where is the Bombay I knew and loved and felt so safe in? Where as children we would play in the streets and ride public transport without adult accompaniment, jumping in and out of running buses, trams and trains? The trams were the easiest and the best fun, they were so slow and safe. Roller skating behind ambling victories trailing on a long rope was more risky. There was a time when everyone was welcome in the city by the sea, from north, south, east, west and yes, even from overseas.

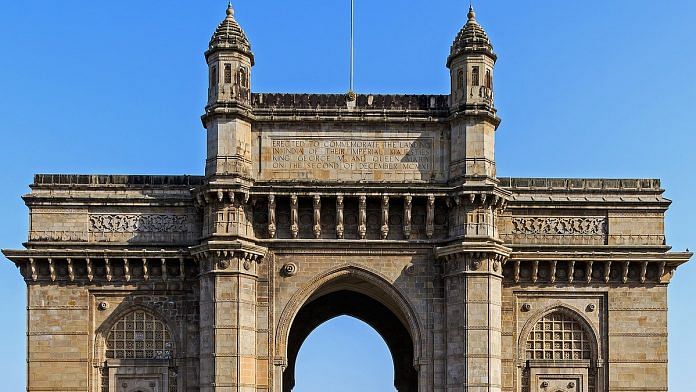

All could boast: Bumbai Meri Jaan, Meri Rozi Roti, Meri Jivan Dharti! But when Bombay became Mumbai, Mumbaikars became islanders, as when it was a fishing village, and the city seems no longer the gateway to an India of the future, but just an island off the west coast of Mahatashtra for ‘sons of the soil’.

Also read: O.P. Nayyar, the untrained musical genius who was more than just a hit machine

Without even noticing it, that time of innocence and abandon, of adventure and discovery seems lost forever. I wonder where the children play in this imploding city. If they do it must be in video parlours and probably war games to boot. Today Mumbai has become an unending struggle for life and livelihood. We are all becoming urban guerrillas in our own private wars, and perhaps mercenaries in some public ones, constantly redefining the outsider as the enemy: South Indian, North Indian, Muslim, Sikh… How has Bombay once the most cosmopolitan, the most populous, the wealthiest city in the country, become Mumbai for ethnocentric Mumbaikars only? Is this the future of urban India? A future that is already crashing into the present and so hauntingly described in Salvatore Quasimodo’s epigraph: Each alone on the heart of the earth impaled upon a ray of sun: and suddenly it’s evening.

Sudden tragedy makes us companions in pain, exploding into a city that never sleeps. As when there is a surprise terror attack. We stop for a while, pick up the pieces and then hurry on with what’s left of our lives. But there’s no guarantee that there isn’t more of the same coming. Tragedy and pause punctuate our hurried, harried, hustled living! Yet soon enough we exorcise painful residues of haunting traumas. They make us resilient, but then perhaps too selective in our memories, for they have yet to teach us to share and care beyond the passing present. Life must go on and so it does. But how can our shared vulnerability make us more caring? When vengeance is compelling, how can forgiveness be our sword? Can we be instruments of peace together for each other, for all? How can the compassion that melds us together when some disaster strikes, work for lasting peace?

Mumbai has been bombed in 1993, 1997, 1998, 2002, 2003, 2004, and now 2006. Every

monsoon brings disrupting flooding. In July 2005 a cloud burst brought most a metre of rain in three hours, which paralysed the city for over a week. The citizens pitched in to save the day. What next? There should be a system of ‘quotas’ for these disruptions! And in the meantime, we just have to hang in there and hope that if not good sense, at least common sense will prevail. Too many of those who want to teach others a lesson seemed to have learned the wrong ones themselves. For without a collective consensus, which still evades us, we can only end up more divided and more helpless, each alone and impaled by fear.

But we don’t seem to be able to get our act together, to get a handle on where we are and why we keep going. But we are moving, moving on a carousel, round and round, up and down, while some people from the outside, we’d like to think, take potshots at us. Sometimes it’s the rain gods who send us tsunamis from the sky; sometimes it’s the demons on the ground who use terror against the defenceless. Yes, we are ever so proud of our city, Mumbai meri jaan! But how do we heal and cope with our brokenness? Surely, we need more than just the spontaneous generosity that a disaster evokes. This calls for a more sustained human fellowship of mutual respect and personal freedom, and we still have a long way to get there.

Travelling on the suburban trains in the city, I remember reading a railway notice: ‘Young and old persons are travelling unaccompanied; please accommodate them and look after them.’ Today the notice would read: Do not befriend strangers, report any suspicious persons. I tell myself if there’s a blast in the crowded train, I may just see the flash, I might not even hear the noise. And then, if I’m lucky, for me there’ll be just silence, and hopefully light, not darkness! Maybe that will be the only light at the end of this tunnel. But what of the others left behind in the dark? What kind of city will be left for them? They still must board the trains for a livelihood. Mumbai, meri rozi roti!

The next time I’m on the train, I’ll close my eyes and when I open them again, hope the city will still be there, and those unimaginable horrors prove just imaginary? It’s a game I used to play as a child when I was frightened and alone. I seem to be going back to my roots. But I can’t run away from my life, my livelihood, my home? And if I do leave Mumbai, will Mumbai ever leave me? Mumbai meri jaan, Mumbai meri rozi roti, Mumbai meri jivan dharti!

Excerpted from ‘A Clown for God, A Clown for Others: Recollections of an Indian Jesuit’ by Rudolf C. Heredia. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2022.

Excerpted from ‘A Clown for God, A Clown for Others: Recollections of an Indian Jesuit’ by Rudolf C. Heredia. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2022.