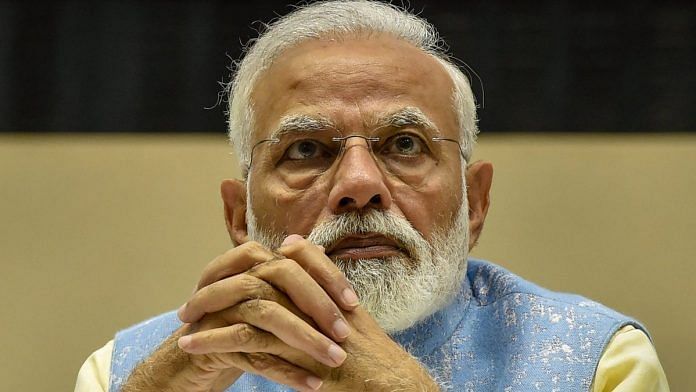

Modi was in many ways an unusual RSS swayamsevak. A compelling public speaker with a talent for organization, he was never content to be a faceless, self-effacing soldier for the organization that nurtured him.

Steadfastly loyal to the RSS and its traditions, he was at the same time also a fierce individualist. In an organization where unquestioning obedience to the superior was the norm, Modi stood out for his questioning and argumentative ways. His was also a restless mind. Whereas many RSS apparatchiks were grounded in inherited certitudes, Modi was forever pushing the frontiers of his own intellectual development.

At one time he imagined a future for himself as a monk in the Ramakrishna Mission—an order established by Swami Vivekananda at the beginning of the twentieth century. When the Mission turned down his request, he resumed his life in the RSS. But what inspired him was not so much the Hindutva of the RSS stalwarts Keshavrao Baliram Hedgewar and ‘Guru’ Golwalkar but the message of national resurgence and activism that Swami Vivekananda blended with his spiritualism. Modi was moulded by his readings of Vivekananda and not least the Swami’s sense of India’s global mission.

Also read: How RSS pressure forced pro-business Modi to turn BJP’s 2019 ship towards populism

Modi never had any formal training in economics, and nor did he have any administrative experience before he assumed charge as chief minister of Gujarat in 2001. What he did have, however, was an open mind and an appreciation of the Gujarati spirit of entrepreneurship and global orientation. Whereas Mahatma Gandhi, India’s most famous Gujarati, had stressed austerity and debunked the West’s idea of progress, Modi was a fanatical modernist. To him, it was a travesty that India was still riddled with poverty, backwardness and insufficient opportunities for personal growth. His exposure to the West through travel and his interaction with the successful Gujarati diaspora convinced him that India could not afford to be Third World. India too needed the best the world had to offer, both in terms of services and infrastructure. Temperamentally at least, he was never at ease with the chalta hai (loosely translated as ‘anything goes’) attitude that often coexisted with a sense of fatalism.

Modi was particularly attracted to technology as a means to improve the quality of administration, enhance the average citizen’s quality of life, and connect Indians with each other.

In an earlier era, the RSS–BJP ecosystem had viewed the revolution in technology as a Western phenomenon and linked to consumerist lifestyles. The BJP leader from Mumbai, Pramod Mahajan, was, for example, constantly chided for the enthusiasm with which he used mobile phones at the time of their introduction in India in the late 1990s. Apart from defence where technological upgradation of the military was constantly demanded, there was an instinctive sympathy with ‘development’ programmes that stressed the overriding importance of ‘appropriate technology’.

Also read: Narendra Modi may not like Jawaharlal Nehru, but still wants to be like him

During his tenure, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi contributed immeasurably in sensitizing India to the importance and the opportunities presented by the rapid strides in information technology (IT). Modi was certainly one of the early converts to the idea. As chief minister, he introduced IT in different areas of governance, particularly land registration, revenue administration, and the regulation of transfers and postings in the lower bureaucracy. Modi was among the first to experiment with biometric systems to ensure attendance of teachers and students alike in government schools. ‘Perhaps no State government,’ wrote journalist Uday Mahurkar in his study of the Modi administration in Gujarat, ‘has used latest technology to bring transparency in governance to reduce delays and redtape as the Modi government has.’

The success of e-governance in curbing discretionary powers of the bureaucracy—the principal source of corruption—yielded rich political dividends for Modi in Gujarat. It also established his reputation all over India as a politician who went beyond ethical homilies and demonstrated that the levels of corruption could be brought down significantly. At a time when India was agitated by the sheer scale of the reported scams—notably the ones involving telecom licences, coal mining leases, and the organization of the Commonwealth Games—under the UPA government, Modi came through as a politician who had the courage to fight the menace head-on.

As prime minister, Modi has used the tools of e-governance in every sphere of life. From the issue of driving licences and passports to tax administration, life has become much easier for the ordinary citizen. The sheer harassment that was the hallmark of everyday existence in India has come down exponentially, and so has the incidence of petty corruption. The Aadhaar biometric system of personal identification—a scheme conceived by the Manmohan Singh government—was put into operation and has become an important instrument in ensuring tax compliance and fighting corruption. Likewise, the administration of Goods and Services Tax (GST) has been marked by a parallel introduction of online systems, a move that was, however, contested by a section of traders accustomed to dodging local taxes by innovative means.

Also read: RSS sends tacit message to BJP: Deliver on promises which brought you to power

From the day he assumed charge as prime minister, toning up the administration and introducing systemic reforms have been the priorities of Modi. In his first Independence Day address from Delhi’s Red Fort in 2014, he called for a moratorium on all contentious issues for ten years, a period that could be better utilized to addressing bread-and-butter issues. This prompted the charge that Modi was intent on reducing politics to a set of managerial choices. A more sinister connotation attached to his appeal was that the managerial focus would enable the BJP to rejig the fundamentals of Indian nationhood and break down the Nehruvian consensus without the glare of publicity and controversy.

The wariness and the belief that Modi was being wilfully disingenuous stemmed from the inability to grasp that the prime minister himself was not being guided by doctrinaire prescriptions. He was principally guided by considerations of feasibility, efficiency and speed. Like a former president of India, A.P.J. Abdul Kalam—a man widely respected and admired in India—Modi too believed there were aspects of nation building that were above partisan politics.

In a curious way, this approach had a lot in common with the approach of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister who, ironically, Modi believed had exercised all the wrong choices. Nehru too felt that his grand plans of economic development through the Five-Year Plans were above politics and that the big dams, steel plants and centres of educational excellence were the new ‘temples of modern India’. However, in line with the ideological predilections of the times, Nehru simultaneously believed that the state, guided by a technocratic elite, must play a pivotal role in the reconstruction of India along modern lines. Nehru and Modi were linked by a common commitment to modernity. However, whereas Nehru emphasized the role of the state and the public sector, Modi felt that the state should merely be an efficient facilitator and focus its energies on creating a modern welfare state. The task of generating livelihood, he felt, must be left to India’s entrepreneurs who had earlier been harassed and put down by an over-regulatory regime that encouraged corruption and cronyism.

In the election campaign of 2014, Modi spoke about ‘minimum government, maximum governance’—the first occasion any serious claimant for power had attempted to put the role of the state back in focus. To this was added civic virtues such as cleanliness, good health, adherence to laws, and respect for women. Enthused by his approach, business and industry as a whole extended substantial backing to the BJP in the 2014 election.

This excerpt from Awakening Bharat Mata: The Political Beliefs of the Indian Right has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Awakening Bharat Mata: The Political Beliefs of the Indian Right has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

I am seeing a NEW face of PRINT. Perhaps the recent success of Hon.Prime Minister might have made “the PRINT” to take a New line.However don’t forget to disagree wherever necessary.

A rare aricle giving insights into the working of PMs mind.But Author can also throw light as to compulsions for Modiji to centalise eveything.