It appears from what is said above that the word ‘republic’ covers all that is meant by the term ‘democratic’. Our own Constituent Assembly initially took the view that since the word ‘republic’ contains the word ‘democratic’, it may be unnecessary to use both. This may have been in keeping with the French republican tradition, where the two terms are used interchangeably. Yet, After announcing its commitment to sever its links with an external, imperial monarch and all existing and future claims of local rajas and make India a republic, Ambedkar and Nehru conceded that since an undemocratic republic is conceivable, a separate commitment to democratic institutions is necessary. This decision was correct. It was wise to keep both terms in the preamble. The idea of the republic conveys that decisions shall be made not by a single individual but by citizens after due deliberation why we need a constitution in an open forum.

But this is consistent with a narrow criterion of who counts as a citizen. The ancient Roman Republic was not inclusive. Ancient India probably had aristocratic clan republics that were far from democratic. In ancient Greece, slaves, women and foreigners were not considered citizens and excluded from decisionmaking. Indeed, for many Greek thinkers, democracy had a negative connotation precisely because it was believed to involve everyone, including plebians, who we contemptuously call ‘the mob’. What the term ‘democratic’ brings to our Constitution is that citizenship be made available to everyone, regardless of their wealth, education, gender, perceived social ranking, religion, race or ideological belief. Democracy makes the republic inclusive. No one is excluded from citizenship; all of us have the right to vote.

At the same time, if voting is restricted, for practical reasons, only to choosing representatives who make laws and policies in the name of the people, then citizens must at least have the right to be properly informed and seek transparency and accountability from their government. A republic must, at the very least, have perpetually vigilant citizens who act as watchdogs, monitor their representatives and retain the right to contest any law or policy made on their behalf. By going beyond mere counting of heads, the term ‘republic’ brings free public discussion to our democratic Constitution. It gives depth to our democracy. It is mandatory that decisions taken by the representatives of the people be properly deliberated, remain open to scrutiny and be publicly and legally contestable even after they have been made.

When the farmers came out on the streets to peacefully challenge the three farm laws made by the current government, they exercised not only their democratic rights but exhibited the highest of republican virtues. It is to celebrate such political acts of citizens that we have a designated republic day.

Also read:

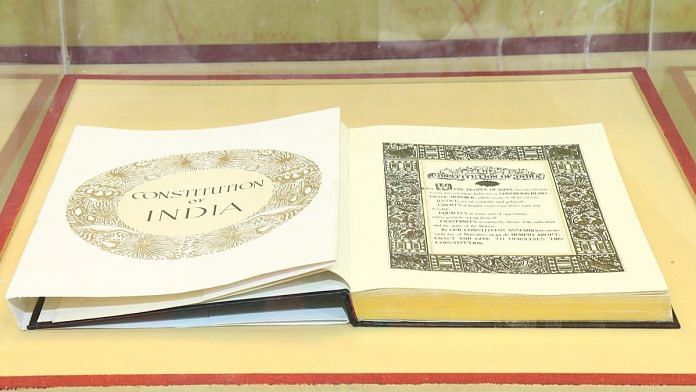

Why We Need a Constitution

The judgement by the Supreme Court clarifying the jurisdictions of Delhi’s lieutenant governor and its elected representatives and specifying the limits of their powers once again underscored how fortunate we are to have the Constitution. Why should gratitude be expressed for living under a constitutional democracy?

Why do we need a constitution? Since an individual’s own personal power is severely limited, nothing valuable can be attained without the collective effort of individuals. A boulder cannot move even by an inch when pushed by an individual but with help from others, it can go places. Most human good—health, education, infrastructure, peace and harmony, economic growth, leisure and enjoyment, art and literature, narratives of self-understanding and collective heritage—are realised by assembling power. However, once constituted, this indispensable collective power to do or achieve things can be used not to realise the collective good but for one’s own exclusive advantage—to secure things only for oneself. This can be done by forcing others to do what they would not otherwise do—to get them to act against their will—for one’s own benefit.

Also Read: India’s democracy goes beyond the last mall in Noida. Rural feudal rich are feeling the pinch

Checking Tyranny

A typical feature of all, particularly modern, societies is that this public or collective power is largely vested in the state relatively separate from society. It follows that state power meant for everyone’s good can be used by some over other members of society to benefit just a few of its functionaries and their friends. Since the formation of states, humans have felt the need to not only garner collective power but also limit it so that it is not exercised whimsically and arbitrarily for self-aggrandisement and against the basic interests of the people.

This is the key reason why we have the Constitution, which is not just any odd assortment of law and institutions but a framework of ground rules that acts as a bulwark against the tyrannical use of state power to dominate and oppress others. In short, constitutions strive for a delicate balance to ensure that the collective power of society invested in the state is neither dissipated or fragmented to become ineffective (for this results in lawlessness and anarchy detrimental to the realisation of the good life) nor so tightly organised and untrammelled that it takes away our freedom and becomes oppressive.

The potential to abuse public power, an ever-present possibility in all states, is inherent in the very exercise of it. Thus, the earliest constitutions of the world developed to check the tyranny of our rulers. This idea of the Constitution presupposes an unbridgeable distance between the people and the state—a powerless people who need the help of constitutional law to control state power.

This excerpt from Rajeev Bhargava’s ‘Between Hope and Despair: 100 Ethical Reflections on Contemporary India’ has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

This excerpt from Rajeev Bhargava’s ‘Between Hope and Despair: 100 Ethical Reflections on Contemporary India’ has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.