Is it right to call Ladakh, Zanskar and Spiti Valley India’s ‘Little Tibet’ or ‘Greater Tibet’? The heavy cultural and military influence may have coalesced their identities over time. But for American professor-historian Robert Linrothe, the description is “maddeningly imprecise and misleading”.

Presented during a scintillating history lesson at New Delhi’s India International Centre on 11 March, Linrothe’s thesis held an unwavering faith that Ladakh and Tibet are not the same.

The professor from Northwestern University in Illinois, US, has been travelling to Ladakh on a yearly basis for more than three decades. And his fascination with the region led him to research the complexities of naming the areas in the Western Himalayas.

A silence befell the audience as the art historian showed pictures of cafes, restaurants, and shop signs that were all laced with ‘Tibetan’ in their names. But he said that the history of the region is far more complicated than what has been promoted.

“Food, clothes and even the geographical and climatic conditions in Ladakh are closely akin to that of Tibet as the country’s cultural pressure has been historically uniform, and even given Ladakh a western Tibetan dialect. An old scholar once said that, culturally, Ladakh is Tibet,” Linrothe said.

But this closeness has been widely misunderstood.

“Geography, culture and history can all be very messy things. In the absence of adequate research, it is much easier to homogenise (them). Which is why we are here to answer these questions today,” said Siddiq Wahid, professor at Shiv Nadar University, who moderated the discussion.

Also read: Pangong Tso will be the highest frozen lake marathon. Aim is Guinness, climate consciousness

Military invasions

The attribution to another culture has much to do with military invasions of the past.

“There is a long history of invasions and wars between Central Tibet and Ladakh. This started around the 8th century, when Central Tibet occupied Ladakh. There were also invasions by West Tibet in the 10th and 11th centuries,” Linrothe explained.

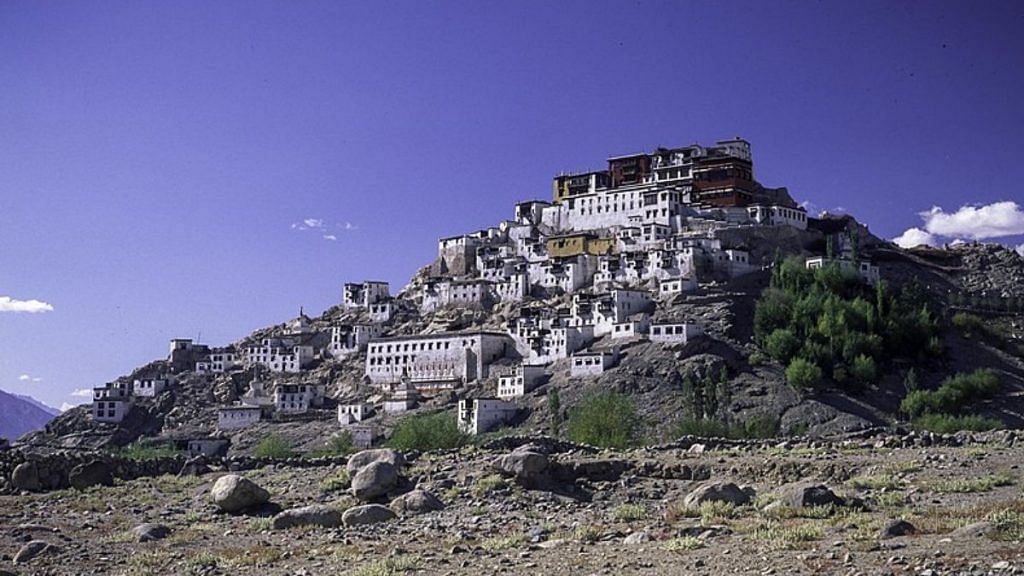

But while there were connections, Linrothe showed images of petroglyphs to highlight the many distinctions between the two regions. Casually identifying them as the same only hinders proper historical enquiry, he said.

The historian showed rock paintings to highlight the regions’ distinct identities. “The art of the early historical period in the areas of Spiti, Ladakh and Zanskar were not Tibetan until much after the 11th century invasions. Even then, it was not exclusively Tibetan.”

Comparing Tibetan invasions to the present situation in Ukraine, Linrothe said, “Military occupation does not necessarily mean participation. This leads to the idea of a false but common identification.”

But today, a pattern of assumptions pervades when one thinks of Ladakh and Tibet. Perhaps the shop signs and eateries reading ‘Tibetan cafe’ may urge one to think that the area’s Tibetanisation was positive. It may not always be the case, the historian argued.

Also read: ‘Celebrated too soon’ — Ladakh fights for identity, autonomy more than 3 yrs after Article 370 move

Both cause and effect

Despite their various run-ins, Ladakh was not necessarily subsumed by Tibet. Buddhism, too, was probably not a product of Tibet’s cultural impact on Ladakh and rather has a much more complex history that requires deeper digging, he said.

Linrothe quoted from Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang’s book A History of the Tibetan Empire — translated in English by Meghan Howard — that the Dunhuang, an old manuscript, provided glimpses of the Tibetan world prior to the emergence of Buddhist tropes through which the empire was later viewed.

“As a matter of fact, Buddhism was introduced in the upper valleys of the Indus much earlier in the 7th century,” said Linrothe.

He further said that the language and culture of Ladakh and Baltistan were perhaps already Tibetan in a way. Thus, the incorporation of Ladakh into the old Tibetan empire might have been both a cause and an effect.

“From some standpoints, I understand why we see these regions as Tibet itself. But there is significant archaeological evidence signifying that it isn’t,” he added.

Many in the audience agreed with Linrothe’s thesis. People of Ladakh, too, it seems, feel strongly against equating their culture with that of Tibet. A woman in the audience said many Ladakhis at her workplace often humorously berate her for juxtaposing their culture with that of Tibet.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)