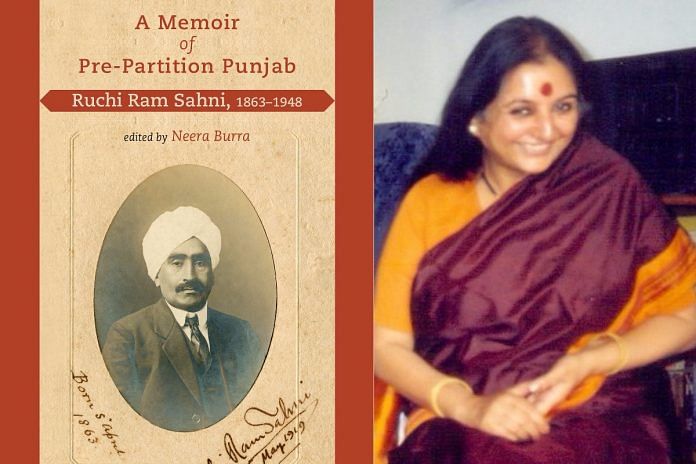

‘A Memoir of Pre-Partition Punjab’ traces the life and work of Ruchi Ram Sahni; freedom fighter, educationist and story-teller, Sahni wore many hats.

This book tells a story within a story. While Ruchi Ram Sahni’s life forms the substance of the book, the discovery of that life, and its framing and bringing to public attention is a story in itself.

It begins with the editor, Neera Burra, Ruchi Ram Sahni’s great granddaughter finding herself a bit at a loose end after having taken early retirement, and finding, suddenly, the time to be curious, to ask questions, and to explore. She begins by following her mother’s request to locate a particular branch of the family in Mumbai.

And here she finds not only the family, but a veritable treasure trove of writings, including Ruchi Ram Sahni’s autobiography that forms the substance of this book. It is also this encounter that makes her realise, as such experiences have done for so many of us, that she’s always been aware of the story she’s now found, but that she has never been attentive to it.

Once the search begins, a wealth of materials find their way into it: letters, journalistic articles, newspaper archives, oral accounts, and even direct memory from a 100-year-old granddaughter whose memories are, surprisingly, sharp and clear.

Ruchi Ram Sahni, whose life spanned a little less than a century (1863-1948) emerges as a man of many parts. At a young age, when he was ready for high school, he decided to travel from Dera Ismail Khan to Jhang, where the nearest high school was. The nearly 100-mile distance meant traversing rivers, spending nights in the middle on small islands, riding on camelback and finally arriving at his chosen school.

Once there, admission was not a breeze, but Ruchi Ram was both determined and dogged and several days of negotiation with the headmaster finally yielded results and he was able to gain admission.

If education was important to him, so was secularism, by which he swore and lived, and on which he acted, at one point returning an award out of solidarity with his Muslim brethren. Equally, despite turning to the Brahmo Samaj and facing considerable criticism for this, he remained friends with people of ideologically different persuasion. It was a mark of the times that ideological differences still allowed for friendships and for intellectual debate.

Ruchi Ram was also the quintessential teacher, and there is a lovely moment when he describes learning, while still at school in Dera Ismail Khan, about the Russo-Turkish war that created an ‘extraordinary stir among the Muslim population’. On his way home from school, the young student had to pass through a bazaar populated by Muslim shopkeepers and artisans. One day he was questioned about the war by an indigo dyer and from that day on, what he learned at school was passed on to the people in the bazaar, which then became a hub of considerable political discussion.

Later in life, disappointed at having been superseded by someone much younger and less experienced, because he would not compromise, Ruchi Ram turned to science and made a name for himself in this field too. He worked, first in Germany and then in the UK, with some of the best minds in this field and once back in India, became a teacher of Chemistry.

A man of wide-ranging interests, Sahni had a long-term connection with The Tribune as trustee and regular contributor. Here, he formed a lifelong friendship with the newspaper’s founder, Dyal Singh Majithia, a man who is very much in the news today as the governing body of the college named after him attempts to wipe that association out.

Once back in India, he became deeply involved in the freedom movement, particularly in Punjab, where he was also closely associated with the Sikhs. His tastes were eclectic, from bulbuls to books and from storytelling to scientific innovation. He recounts how, after he developed a taste for reading books he created what he calls a ‘poryphery tree’ which carried summaries of books he’d read for quick reference, a lovely idea if ever there was one.

Neera Burra’s edited volume includes an introduction, and an annotated version of the autobiography. While I found the introduction useful and the autobiography itself fascinating, I was not so sure of the annotations that seem to me as a general reader, a bit excessive. But this is a mere quibble, and should not detract from the value of the book.

I’d like to end with an episode: recently a friend took me to meet Indira Pasricha, Ruchi Ram’s oldest surviving granddaughter. Now, 100 years old, Indira Pasricha is today a staunch supporter of the ABVP and it was when I saw a mention of her in this book that I realised how much political beliefs and loyalties can transform in just a few generations. A sign of our times perhaps.

Urvashi Butalia is an author and publisher.