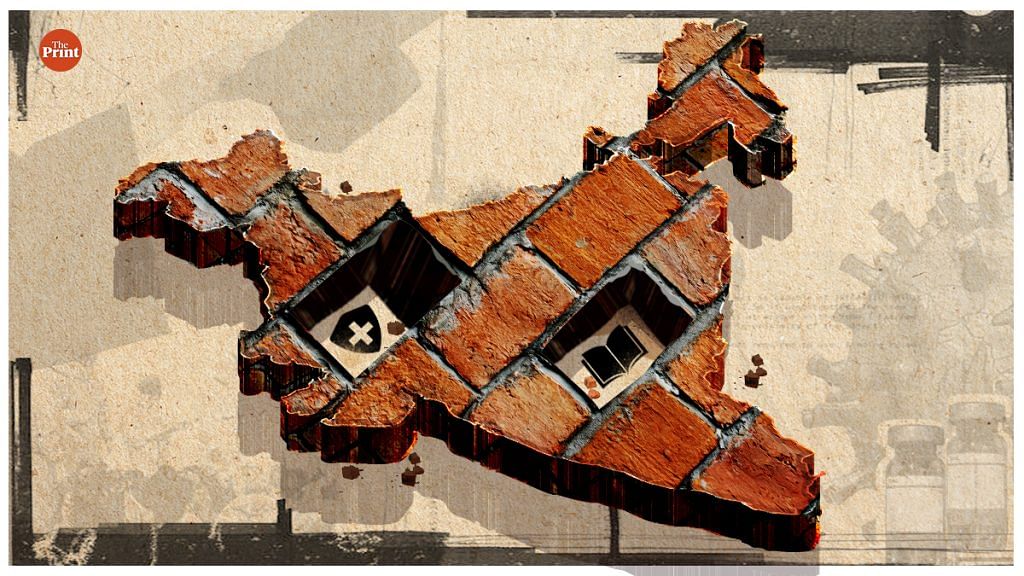

It is a stark testimony to the medium-term havoc caused by the Covid pandemic that many countries, including India, have suffered a setback during 2020 and 2021 to their human development index (HDI) — a composite of indicators for health, education and income.

After sustained, if somewhat slow progress over decades, India has seen a setback on life expectancy as well as on the education front. Interestingly, the lowering of its HDI score happened more in 2021 than in 2020. India’s index is now only fractionally above what it was in 2015.

Some of the damage can be undone quickly. Absent the spike in the death toll on account of Covid, life expectancy could recover its loss of two years. Getting back quickly to the earlier attainment level of education may be more difficult.

While some of the loss of index value will therefore survive into the future, it does not necessarily affect the country’s index rank in relation to other countries, which is down by just one over the six years to 2021, from 131 to 132. This suggests that the slide in index values is par for the course. Many countries have withstood Covid better, others have not.

Two other points are of note. First, countries like Bangladesh rank better on the non-income indicators, unlike India which does the opposite. So while Bangladesh has lower income, it has a better over-all index score. Bangladesh is also notable for not having suffered any setback in its human development indicators during the Covid years.

In comparison, if India were ranked purely on health and education, leaving out income, its rank would be six notches lower. Which is to say that the country’s health and educational attainments are short of what they should be at its income level. This has been true for some time.

Second, it is a sobering thought that while India continues to be a typical “Medium Human Development” country, Vietnam graduated recently into the “High” human development category, while Asian neighbours like Malaysia and Thailand have moved into the “Very High” attainment category. If India were to improve its indicators at the pre-Covid rate, it would probably take till 2030 to move from “Medium” to “High”. Looked at another way, India’s index is roughly where China’s was at the turn of the century, i.e. a lag of about two decades. The distance that separates India from its primary strategic rival is now so large on so many fronts that the two countries are effectively in different orbits.

Also Read: Economy remains under Covid shadow. 6% growth will be a big achievement for India

Still, it might make sense to focus on closing the gap with regard to health and education, relative to income — and, thereby, to broaden the primary objectives to take in more than just economic growth. For, while India is now the fastest-growing large economy, its indicators on health and education do not show the greatest improvement from one year to the next. In this context, Amartya Sen’s description of development as the building of capabilities is one that is worth keeping in mind.

Debate on the subject has long pointed to the lack of public spending on both health and education. India is an outlier on both, in that private spending significantly outdoes public expenditure — something that works to the disadvantage of the less well-off. The other point to note is the regional dimension — what are known as the Bimaru states continue to languish and pull down the national average. Infant mortality in Bihar, for instance, is two-and-a-half times what it is in Tamil Nadu.

Recent initiatives like the introduction of health insurance for all those who cannot afford it, should make a difference, but are not enough. So the Narendra Modi government’s preference when it comes to public spending, to focus on the physical rather than social infrastructure, needs a re-look. Investment in the physical infrastructure has gone up by as much as 1 per cent of gross domestic product in recent years.

That is great, but not matched by investment in the social infrastructure. While India needs to improve its physical infrastructure, that is no less true of social infrastructure. Capability-building has to be understood and addressed in its full meaning.

By special arrangement with Business Standard

Also Read: India has joined the global chip race. Question is, should it fly solo?