Blame the Nehruvian consensus for how badly rich people were shown in Hindi movies.

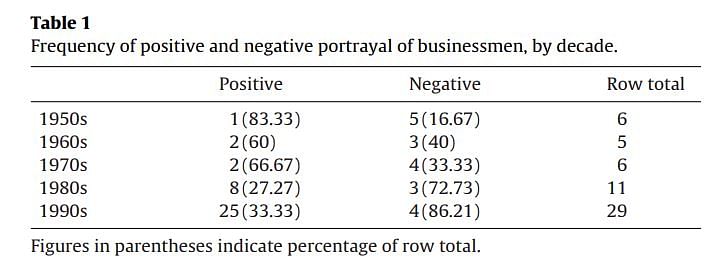

The Nehruvian consensus in India relied on certain prevalent ideological beliefs for its legitimacy. Foremost among them was the suspicion of businessmen and markets that has a long tradition in Indian thought. The beliefs made it possible for the state to sustain a strong role in economic affairs within a democratic setup. The beliefs weakened in the 1980s, and the ideological edifice supporting the implementation of the Nehruvian consensus crumbled.

Mahatma Gandhi wrote that “there is nothing more disgraceful to man than the principle ‘buy in the cheapest market and sell in the dearest’.” Jawaharlal Nehru once famously said, “Don’t talk to me about profit. Profit is a dirty word.”

Indian cinema is rich in ideological content. Two film scholars, K. Moti Gokulsing and Wimal Dissanayake, note that Indian films “belong to the popular tradition of filmmaking and can be described as morality plays, where the forces of good and bad vie for supremacy”.

Peter Biskind — a former editor of the periodical American Film —writes that “to understand the ideology of films, it is essential to ask who lives happily ever after and who dies, who falls ill and who recovers, who strikes it rich and who loses everything, who benefits and who pays — and why”.

Hum Aapke Hain Koun (1994) is perhaps the most successful film of Hindi cinema, earning (at the time) an unprecedented Rs 650 million. The film is itself not remarkable, but it is remarkable in that it glorifies a wealthy industrialist family and thus signifies a turn in the discourse about wealth.

Watching Hindi films from the 1950s, one would get the impression that wealth is something that people simply have, as a manna from heaven. Either you have it or you do not — rarely are the characters shown earning it. The wealthy in Do Bigha Zameen (1954), Jagriti (1956), Mother India (1958), Madhumati (1959), and Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam (1963) are landlords who have inherited their estates. They are shown to while their time away smoking (Jagriti), hunting (Madhumati) or drinking and womanising (Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam).

In such films, only the poor are shown to work, and more than anything, it serves to emphasise their wretchedness, as in Mother India and Do Bigha Zameen.

The movies of the 1950s, therefore, portray a world in which work does not pay, and the only way out seems to be getting coopted by the wealthy — directly or through the state.

In such a world there is little scope for creating wealth — only of redistributing it.

Bandini (1964) is the earliest film in the sample in which the rich are shown to work. Deven, the car-owning doctor, works hard, as when he attends to his patients in the middle of the night. In Guide (1967), the car-owning archaeologist works long hours at excavation sites and, as a result, his wife leaves him. In the films of the 1960s, work begins to pay. Though the characters of films are shown to earn their wealth, their lives are often shown to be marred by personal unhappiness and immorality.

The two-careers couple in Rajnigandha (1975) are living the good life in an upscale flat in Bombay, but are too busy to have children, as the wife bitterly notes. The protagonist in Bhumika (1977) achieves professional success only by compromising her chastity and enduring scorn and separation from her family. The wealthy father in Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985) makes his fortune by skimming money from government contracts to clean up the sacred river Ganges. The father of Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan) in Shakti (1982) exhorts his son to not accept employment from a particular businessman because his activities “seemed dirty”. Amitabh Bachchan replies matter-of-factly, “Well, all businesses are dirty.”

The films from 1964 to 1985 thus display an ambivalence. Wealth is shown to arise from work, and is thus legitimate, but is shown as bad for the soul. The ambivalence is best articulated in Deewar (1975), in the famous dialogue between two brothers that ends with “I have got mom”.

The ambivalence is shed beginning in the late 1980s. The ‘Best Film’ award-winning films show businessmen as extraordinarily moral. For example, Ashok Mehra (Raj Babbar) in Ghayal (1990), the older brother of the film’s hero, dies while trying to protect his business from being used as a cover for anti-social activities. Maine Pyaar Kiya (1989) and Hum Aapke Hain Koun both revolve around families headed by benevolent patriarchs who are self-made industrialists. In contrast to the rich of the 1950s, who were unfailingly wicked, the wealthy are now solicitous of their family members (including women) and magnanimous towards their servants, with whom they are shown singing, dancing, and praying.

Wealth has become unproblematic.

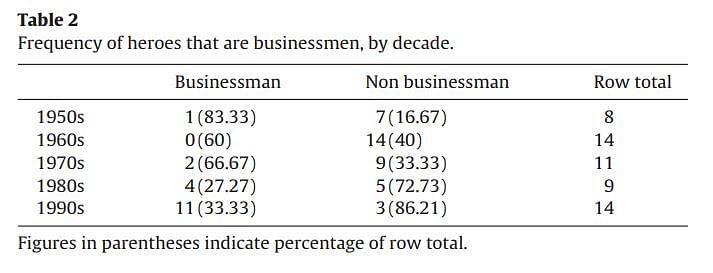

Gone are the days when the hero was a vagabond (as in Jis Desh Mein Ganga Behti Hai, 1962), a dutiful servant (Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam), a street urchin (Boot Polish, 1955; Dosti, 1965) or running an orphanage (Brahmachari, 1969). Now the heroes are unmistakably bourgeois — they manufacture cars (Hum Aapke Hain Koun), shirts (Hum Hain Rahi Pyaar Ke, 1994), and sell bikes (Jo Jeeta Wahi sikander, 1993). They tend to be exporters (Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, 1999) or are successful expatriate businessmen living in the West (Lamhe, 1992; Dilwale Dulhainya Le Jayenge, 1996). They are also fabulously rich — they holiday abroad (Lamhe; Dil toh Pagal Hai, 1997) and live in palatial homes (Maine Pyaar Kiya, Lamhe, Dilwale Dulhaniya le Jayenge, and Dil toh Pagal Hai).

A greater number of viewers have come to cherish enterprise and wealth, and see no contradiction between being rich and a good person. Economists, ever vigilant to the possibility of endogenous causation, may point out the possibility that the ideological change reflected in Hindi films might be a consequence of liberalisation rather than the cause.

But it is to be noted that the ideological change is visible in the films of the 1980s, preceding the wave of liberalisation starting in 1991. It lends support to the notion that the ideological change, reflected in films as early as 1980, was a cause rather than a consequence of liberalisation. Surely, once the liberalisation got underway and people were making money, austerity and self-denial must have gone out of style, making liberalisation even more acceptable. Policy and ideology, in this case, reinforce each other. Films are only one reflection of the changing ideology.

This is an edited excerpt from the paper titled ‘The role of ideological change in India’s economic liberalization’ by Nimish Adhia, assistant professor at Manhattanville College. The sample of films that he studied are the winners of the Filmfare award for their respective year in the Best Film category from 1954 to 2007. The full article appeared in The Journal of Socio-Economics.