Writing a few years before Gandhi’s 100th anniversary, Ram Manohar Lohia, arguably the most astute interpreter of his politics, classified Gandhians into three categories. The first was sarkari (governmental) Gandhians, the Congress leaders who used the Mahatma to climb the ladder of power. Mathadhish (priestly, those who run maths) Gandhians, those who presided over the Gandhian establishment, belonged to the second category. Lohia made little attempt to conceal his contempt for both, represented in his mind by Jawaharlal Nehru and Vinoba Bhave.

Against both these orthodoxies, Lohia posited a third type of kujaat (heretic, out-caste) Gandhians who followed Gandhi in unorthodox ways. Lohia argued that Gandhi’s orthodox disciples were not his true legatees. Gandhi, he argued, would be saved not by his faithful followers but by heretics. Lohia, of course, placed himself in this third category. Deeply respectful but instinctively irreverent, he developed some of the key ideas of Gandhi in his own way without parroting Mahatma’s lines.

Also read: Why Gandhi and Ambedkar never engaged with Hedgewar, the founder of RSS

Need to rescue Gandhi

Today, in the midst of the official 150th-anniversary celebrations, we must look for ways to rescue Gandhi from this crass appropriation by an ideology diametrically opposed to the Mahatma’s worldview. Lohia had alerted us about this possibility in his book Marx, Gandhi and Socialism: “Ever since the attainment of statehood [by India], priestly Gandhism is tied to the apron-strings of governmental Gandhism”.

He was of course talking about the nexus between goody-goody spiritual Gandhians and power brokers of the Congress party. As Gandhi was reduced – literally – to a toothless icon of timeless values, ever-smiling on the currency note, the real Gandhi was erased from public memory. Barring a brief period before and during the Emergency, the Gandhian establishment was so cosy with the powers-that-be that it lost its radical edge and the touch with the new generation.

This set the stage for the ultimate appropriation of the Mahatma by the legatees of his assassin. The Sabarmati Ashram closing its doors to the victims of the 2002 massacre signalled this shift. As the BJP rose to power, first in Gujarat and then at the Centre, it was not difficult for it to take over Gandhian institutions. Barring exceptions like the Gandhi Peace Foundation and the Sarva Seva Sangh, the vast network of Gandhian institutions either withered away or turned collaborators.

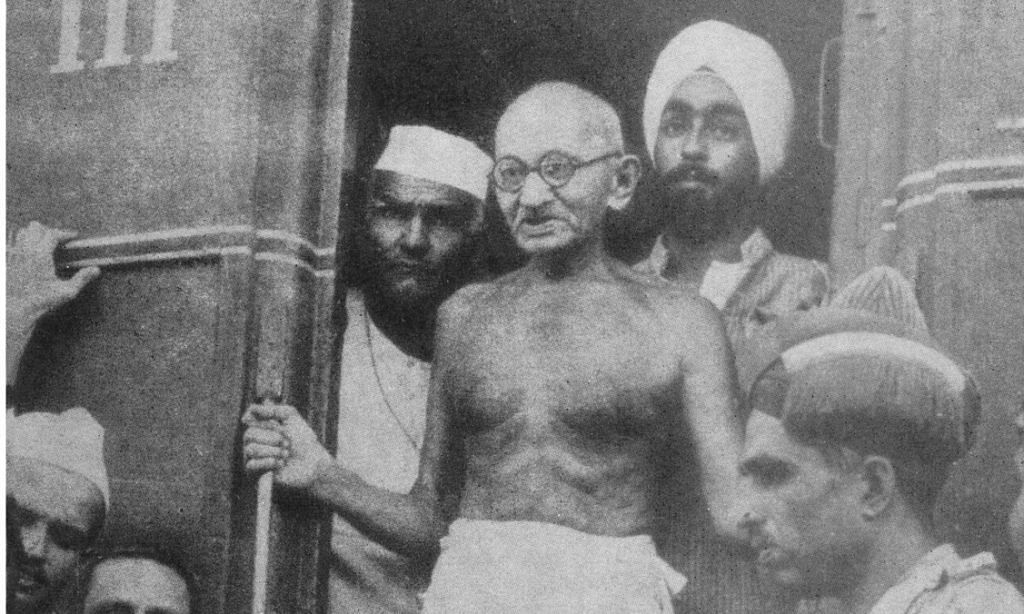

Gandhi, now reduced to his spectacles and bald head, is just a mask available for any and every cause. He can be used to promote vegetarianism of the most violent variety. He is the patron saint of the most inane and harmless environmentalism. And, of course, the brand ambassador of Swachh Bharat.

We need to save Gandhi from this travesty of Gandhism. We need heretic Gandhism to save Gandhi.

Also read: Indian liberals must reconsider their rejection of Mahatma Gandhi

Unlearning Gandhi

If the Gandhi centenary was about learning from his life, the 150th anniversary has to be about unlearning his stereotypical image. Polar opposite ideologies of the 20th century – from Marxists and Ambedkarites to the Hindutva brigade – joined hands to create this stereotype. Both his admirers and detractors created the image of a goody-goody saint – a traditional, orthodox and conservative Hindu saint – out of touch with the realities of our times and the struggles for shaping the future.

The best way to mark his 150th anniversary would be to start busting this image. Gandhi was no doubt a pacifist, but not at the cost of suffering injustice. He said repeatedly that violence is better than cowardice or meek acceptance of oppression. The uniqueness of his message lies not in his advocacy of non-violence, but in using non-violence as a tool of proactive resistance.

He was a strict vegetarian, but insisted that meat be prepared in his ashram for Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. He advocated protecting nature, but his environmentalism did not rest on superficial symbols. He wanted to challenge the nature of modern civilisation, which is at the root of environmental destruction. He supported a return to pre-modern civilisation, but he was not a traditional man in any sense of the term. His sensibilities, his techniques, his message were informed by a distinctly modern outlook.

Gandhi was a Hindu to his last breath. But he was as far from orthodox Hinduism as one can get. He refused to be shackled by any one religious text, not even his favourite, the Gita. He could brush aside heaps of solid scriptural evidence in support of untouchability by saying ‘this is not the Hinduism that my mother taught me’. His Hinduism was ever-evolving.

From someone who began by defending the varna system, Gandhi went on to become such a trenchant critic of the caste system that he refused to go to any wedding except between a Dalit and a non-Dalit. Equally, while being opposed to Hindu supremacists, Gandhi was no knee-jerk, pro-minority secular politician. He staked and lost one of his most precious friendships, with Ali brothers, over naming the Muslim community as aggressors in Kohat riots in 1924. For all his love for the Bible, he came down heavily on the practice of religious conversions by missionaries.

Also read: Gandhi never celebrated his birthdays, but made an exception on his 75th. For Kasturba

Who is a Gandhi?

Perhaps, the best way to recover Gandhi’s message in the midst of this celebratory din would be to read his life as his message. Over the last decades, those who haven taken Gandhi seriously have reduced him to a writer, or a philosopher, which he was not. His writings were secondary to his principal political actions. He may not have been the best interpreter of his own action.

Let us search for Gandhi in his life and in the lives of those who may not invoke Gandhi, who may not agree with Gandhi, but who are doing what Gandhi would have done. Let us look for him in Shankar Guha Niyogi who combined Gandhi’s teachings with that of Marx. Let us find his meaning in the works of Devanoora Mahadeva who refuses to choose between Ambedkar and Gandhi. Let us turn to Ashis Nandy to understand the meaning of Gandhi’s life and his death Let us look for Gandhis beyond India, beyond the circle of those who have heard his name.

And, above all, let us translate Gandhi’s message in our lives here and now. We cannot talk about Gandhi and remain a mute spectator to the imprisoning of millions of Kashmiris in the Valley. We cannot preach non-violence and turn a blind-eye to the spate of lynchings and other hate crimes. We cannot join the national chorus to celebrate this apostle of truth and not call out those on the national stage who are masters of lies and deceit.

This is not going to be easy. Chanting Gandhi’s name is easy, but following in his footsteps was never going to be easy. As Lohia had alerted us: “By its nature, heresy should be more responsible than orthodoxy”.

Also read: Here’s how Indian films of the 1930s and 1940s used Gandhi in their ads

The author is the national president of Swaraj India. Views are personal.