Sunderlal Bahuguna was one of the pioneering and inspiring leaders of the environmental movement in India, an irreplaceable gem for very diverse reasons. With his Gandhian background, frugal lifestyle and a grounded and cultural base in the Garhwal Himalayas, he was a contrasting figure when compared to other environmentalists or wildlife conservationists of that era who were often from urban, privileged backgrounds. At the time when Bahuguna was beginning to make his impact, in the late 1970s and 80s, his efforts added new dimensions to the already existing fledgling green movement in India, just beginning to take shape.

Bahuguna’s Gandhian background, deeply seated in the larger local cultural and traditional system ensured he was able to straddle both sides of the ideological spectrum—Left and Right, within the environmental discourse and community. Later on during the struggle against the Tehri Dam this brought some controversies and criticisms for him, which in my opinion was somewhat misplaced. The environmental movement in many parts of India is often identified on the Left-of-Centre but to have an impact, you sometimes need icons and leaders who command respect across the political spectrum— Bahuguna was one of those figures.

In 1979, when I first met him, as a student, we were trying to learn about the Chipko Movement. One of the slogans of the movement was from a folk song: Kya hain jungle k upkar? Mitti, paani aur bayar (what are the gifts of the forest? Soil, water and air). Today, you have terms like ‘ecosystem services’ that carry the same meaning. These terms didn’t even exist back then. Bahuguna was a pioneer with respect to moving away the focus from a wildlife-centric approach to conservation that was then the norm amongst many of us, and making it directly relevant for larger environmental aspects as well as the livelihoods of people.

Apart from completely drawing upon the local culture, the poetry of folks like Ghanshyam Sailani, which added considerably to the appeal and charisma of the Chipko Movement, Bahuguna would mention to us about how agriculture and the livelihoods of people in the Himalayas are linked to the health of the forests. He would refer to many species of broad-leafed trees such as Oak. I remember distinctly, the emphasis on oak, and we quickly learnt its importance on that trip and now scientists and local people are worried about the decline of Oak in the western Himalayas due to various climatic and land-use changes.

Bahuguna drew our attention to the importance of Himalayan forest, especially oak-dominated forests, and the role the greens played in maintaining the health of local agriculture and water resources for local communities. So this link between healthy agriculture and healthy forests, and between healthy forests and healthy hydrological systems is something that we learnt from the Chipko Movement and in Bahuguna’s company. That has left an impact. Although now I am a hydrologist by training, basically a scientist, many of the things that I do today involve finding scientific evidence for the things that were mentioned in the Chipko slogans. So, in that sense, it is amazing that those slogans and his approach were the original ideas that form the basis of science-based activism that came in much later.

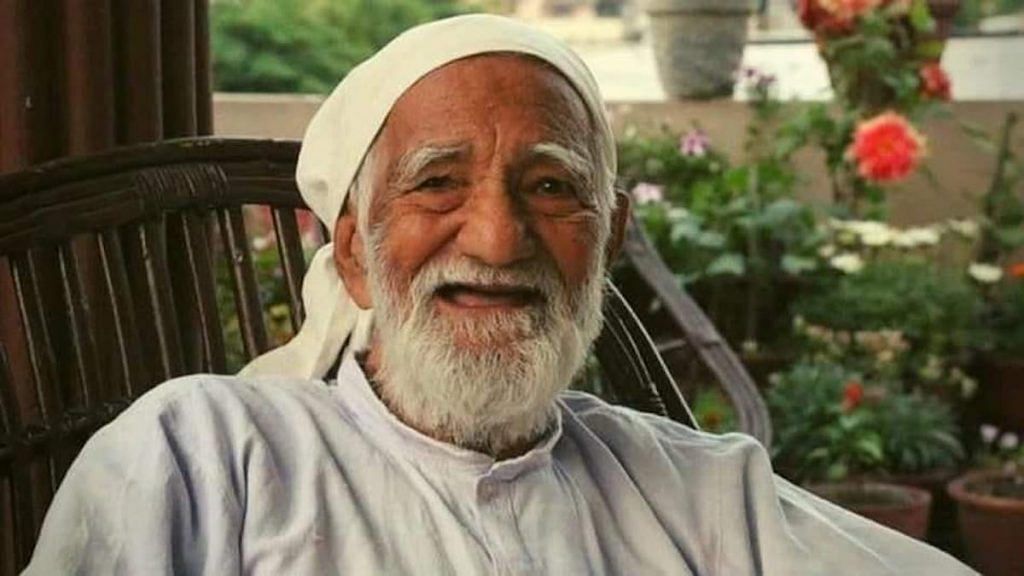

Also read: ‘Guard of Himalayas’, ‘gentle warrior’ — Sunderlal Bahuguna dies of Covid at 94

Bahuguna and activism of today

In the age of high visibility environmental protests, there is a lot to learn from Bahuguna and his ways. In India, we respect frugality and simplicity in our heroes and icons, we respect sages. It appeals to a large section of society. All of this, Bahuguna had.

Some sections of the environmental movement currently in India may not have the cultural and spiritual support that somebody like Bahuguna would be able to command or his ability to command respect across political ideologies and affiliations. That ability is definitely something that makes him stand apart from others. But that also has its own share of controversies. For example, his protest against the Tehri Dam—when other groups like the VHP also became part of it for different reasons, it was criticised by the Left-of-Centre academics. But I look at it very differently. If you really want to have an impact on the environment, on the ground, then you have to draw upon support from various groups. Yes, it is a tightrope walk and a strategy with pitfalls but sometimes it is the only option at critical junctures of a movement. So, on these fronts, I feel some of the criticism against Bahuguna and his approach was somewhat misplaced.

Also read: After nearly 40 years, India’s first river-linking project Ken-Betwa could finally begin

Environmentalist parachuting vs Bahuguan’s grounded style

Conservationists and environmentalists who are firmly rooted in a particular region or a culture definitely have been far more effective, just like Bahuguna was. When you have someone like him espousing the cause, who was rooted in the local environment and culture, all barriers fall apart—language, culture. The lack of roots from the ground eludes many modern environmentalists. Local association and linkages confers a lot of moral authority and confidence in the individual activist.

Bahuguna did that long march from Kashmir to Kohima, the march across the Himalayas an attempt to make his local struggles and discourse pan Himalayas. His focus, however, remained in the western Himalayas in the region now the state of Uttarakhand. His ashram in Silyara is an inspiration to so many people who visited the place and learnt about the Chipko Movement. Bahuguna referred to the fragility of the Himalayas— that we probably shouldn’t have the type of conventional roads in Himalayas that we have elsewhere. He believed smaller villages should be connected with very well-made footpaths linked to few roads. What he said with respect to the hazards of road-building by cutting through mountain slopes is now so relevant, consider the Char Dham project and the widening of the roads and repeated hazards that the Himalayas are facing, like extreme rainfall events and landslides. He was probably the earliest voices that warned us against these dangers, specifically in relation to conservation and sustainable development in the Himalayas.

Also read: Caught between SC & Centre, 24 Uttarakhand hydel projects stuck on paper after 2013 floods

Would his ways work today?

If one had to imagine someone like him emerging from the past and taking the mantle of environmental causes in the present era of a neo-liberal economy and fast-paced information exchange involving social media, he would have to face these newer challenges and reinvent in some ways. Social media with all its benefits and drawbacks is a very different medium. That form of communication and its spread and speed is very different from the time of Bahuguna, who primarily had in-person interactions and through written articles. He wrote extensively, when not travelling or attending meetings. He was fluent in multiple languages—Hindi, Garhwali and English. So that reach made a huge difference at that point of time. It is not clear whether someone like him can emerge and be effective in the current political, social and economic environment.

However environmentalists can still draw some useful lessons from icons like Bahuguna. If someone wants to be an environmentalist as effective and popular as Bahuguna in the current era, you would still need to be rooted and make a difference in the community or region in which you are living, not just through impersonal social media. It’s one thing to do spectacular work in areas far away from where you live but it makes a big difference when you are also doing things in the place where you are actually living and setting an example—something people can still learn from Bahuguna. Perhaps the ability to straddle the ideological barriers in outreach is a crucial requirement for successful environmental activists in the coming years. The environmental movement in India has been given a certain type of label by some sections of the political establishment, and so very few will be able to find listeners across the political spectrum. That’s a weakness or maybe a challenge that the present lot of environmentalists have to grapple with.

Also read: Uttarakhand flood puts focus on Rs 12,000-cr Char Dham project, ministry awaits SC order

A soft-spoken activist

The first trip to Silyara Ashram in Tehri Garhwal and the area was an eye opener for us. Within a few days, we saw a landslide from road building work, and a person was killed. Bahuguna had warned against the environmental dangers of such conventional road-building exercises — how we need to think about the Himalayas in a very different way because they are very fragile. Despite all the scientific learnings, we tend to ignore this fact. But Bahuguha was able to present this case in very simple terms. Those are some of the images that I have, along with the catchy Chipko slogans and songs.

Bahuguna would never talk down to anybody. We were people from an upper middle class background—from Delhi and other cities, but you never felt out of place. He was so gentle and calm, especially when we know that environmentalists can be very shrill and excited and aggressive too. No matter what the issue was, he would maintain his calm.

Sunderlal Bahuguna’s stature in India’s environmental movement will remain as tall as the Himalayan mountains in whose ecology and culture he had deep roots. May his outstanding legacy inspire environmental scientists, activists and local communities to work together to influence policies and conserve Himalayan ecosystems and rivers.

Jagdish Krishnaswamy @JagdishKrishna8 is an environmental scientist and Senior Fellow at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Bengaluru. Views are personal.

(Anurag Chaubey)