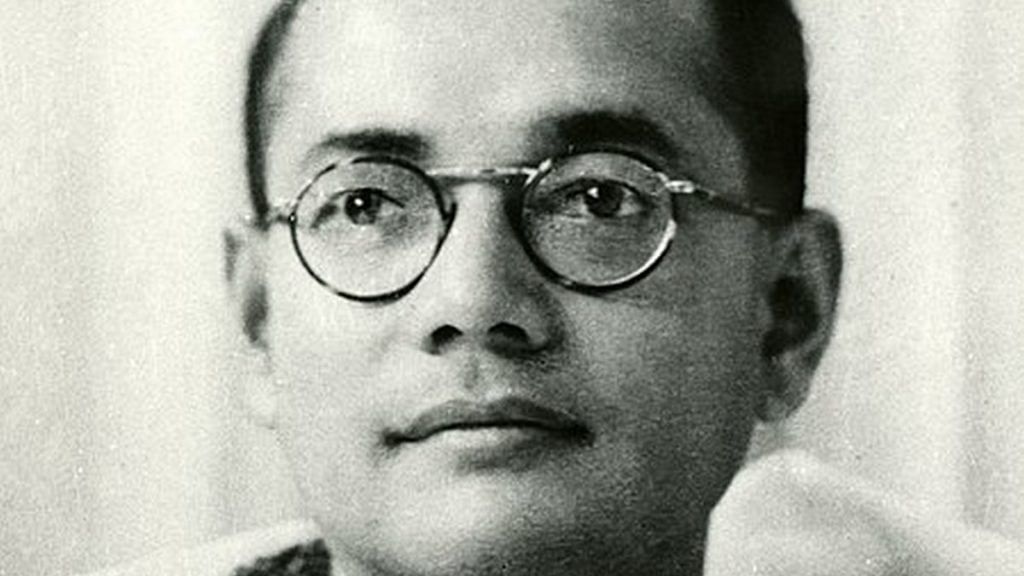

It is well-known that Subhas Chandra Bose held strong views against the politics of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and the Hindu Mahasabha. Much of this narrative has also been the victim of distortions dictated by the agenda of the current political climate. New information shows that not only was the relation between Bose and Savarkar much more nuanced, but they also held each other in high regard despite their political differences.

The backstory

When Savarkar finally became a free man in May 1937, Subhas Chandra Bose was recuperating in Dalhousie after being released from nearly a year of imprisonment and home internment. Bose had defied government orders to return to India in April 1936 from his European exile and, expectedly, was thrown into prison. He was finally released in March 1937. He issued a statement welcoming the return of Savarkar to public life. He hoped that Savarkar would join the Congress. By the end of the year, however, Savarkar had joined the Hindu Mahasabha, aiming to transform it into a national political force.

Their paths didn’t cross as Bose became the Congress president in 1938, except for a brief war of words. When he asserted that only Congress should represent India in any future Round Table Conference, Savarkar protested. The latter argued that only the Mahasabha could claim to truly represent the Hindus, pointing out that although the Congress had won most of the Hindu seats in the previous elections, it did not contest the elections representing solely Hindu interests.

With their radically different political views, the two operated in separate spheres, as Bose clashed with the Gandhian leadership of the Congress and remained too occupied to create an alternative national movement through his party, the All India Forward Bloc.

Also read: India Gate turns a page: Amar Jawan Jyoti merged with eternal flame; famed canopy to house ‘Bose’

Clash of politics

Their politics clashed when Savarkar arrived in Bengal in December 1939 to strengthen the provincial Hindu Mahasabha against the communal government of A.K. Fazlul Huq. The Bose brothers—Subhas and his elder brother Sarat, who was also the Congress leader in the provincial legislature—had been trying in their own way to bring the British government down, but their efforts were thwarted by the intervention of Gandhi, who acted on the advice of G.D. Birla and Huq’s finance minister Nalini Ranjan Sarkar.

Bose’s political mouthpiece, also named Forward Bloc, called Savarkar’s speech in Calcutta ‘tub-thumping’, criticising it for ‘ill-laid emphasis’. In fact, Bose’s criticism reflected his approach towards the communal problem, highlighting the difference with the Mahasabha approach. The Forward Bloc argued that ‘The Hindu Mahasabha has been doing incalculable harm to the idea of Indian nationhood by underlining the communal differences—by lumping all the Muslims together.’

It also mentioned that Muhammad Ali Jinnah and his coterie constituted only ‘a speck in the vast mass of Indian Muslims, and that vast mass is gradually awaking to a sense of responsible nationhood,’ adding that ‘We cannot oblige Mr Savarkar by ignoring the contributions of the nationalist Muslims to the cause of India.’

Also read: Netaji’s legacy partly exploited for political reasons: Anita Bose-Pfaff

It’s more nuanced than simple ‘clashes’

Surprisingly, in spite of his political differences, Bose entered into an electoral alliance with the Hindu Mahasabha for the Calcutta Municipal Corporation in March 1940, a chapter that has remained neglected in his standard biographies. The alliance, however, did not last long and was terminated even before the elections were held, embittering the relations between Bose and the Mahasabha, led by Syama Prasad Mookerjee in Bengal. The question that had remained unanswered until now was — why did a self-proclaimed leftist like Bose ally with a communal organisation like the Mahasabha?

In a signed editorial in the Forward Bloc, Bose explained that he had issued an appeal to all the parties, particularly the Hindu Mahasabha and the Muslim League, ‘asking for their cooperation in the domain of civic affairs, in spite of any differences that might exist on other questions’. The Hindu Mahasabha happened to respond first. While he credited the ‘pro-nationalist elements in the Hindu Mahasabha’ for striking the alliance with him, he blamed ‘the die-hard communal elements . . . who were throughout opposed to any understanding with the Congress’ for wrecking it. The basis of the understanding, Bose claimed, was ‘a sound one’, which would have ensured the ‘triumph of nationalism and not communalism in due course’. Indians needed to come together to resist the domination by the Corporation of the British.

Following the break-up of the alliance, an embittered Subhas Chandra Bose made it clear that he was not opposed to the Mahasabha as such, but its political ambition to displace the Congress. In the Forward Bloc, he wrote:

“It [Hindu Mahasabha] has come forward to play a political role and to make a bid for the political leadership of Bengal, or at least of the Hindus of Bengal, who have been the backbone of nationalism in this country. With a real Hindu Mahasabha, we have no quarrel and no conflict. But with a political Hindu Mahasabha that seeks to replace the Congress in the public life of Bengal and for that purpose, has already taken the offensive against us, a fight is inevitable. This fight has just begun.”

Shortly before he was thrown into prison in July 1940, Bose met Savarkar and Jinnah in his attempt to build a broad coalition for a nationwide movement against the British government but was clearly disappointed with both. He wrote in the second part of his book, The Indian Struggle, that while Jinnah ‘was then thinking only of how to realise his plan of Pakistan (the division of India) with the help of the British,’ Savarkar seemed to be oblivious of the international situation and was only thinking how the Hindus could secure military training by entering Britain’s army in India.’

His long discussions with the two leaders led him to the conclusion that, in his plans for a national uprising, ‘nothing could be expected from either the Muslim League or the Hindu Mahasabha.’

Incidentally, much before the electoral alliance was in the realm of possibility and when Bose was still critical of Savarkar’s politics, the 30 December 1939 issue of the Forward Bloc published an article by S. Krishna Iyer mourned the loss of Savarkar to a sectarian ideology. However, it had astonishingly high praise for the person that he was.

Among other things, the article said, “Mr Savarkar is one of the most romantic figures that the Swadeshi movement of the first decade of the century threw upon the Indian scene. Cast in the mould in which true heroes are made, the whole career of this brave son of Maharastra is one long thrilling tale of daring dreams and adventures with their inevitable concomitant in life-long sufferings. All eyes in the country turned on him when he came out to breathe free air after continuous confinement for the incredible period of twenty-five years. A lesser man would have been thoroughly squeezed out by this repression, but Mr Savarkar stood the test well and brought back absolutely unimpaired the originally rich dower of Nature to him—a keen intellect and a singularly dynamic character. What a startling amount of steel he has in his mental make-up! But alas! instead of consecrating his splendid gifts to the Nationalist cause represented by the Congress, he has chosen to hover round the banner of the Hindu Mahasabha and sing a communal hymn…. Mr Savarkar has evidently been embittered by the sinister growth of Muslim communalism in the country. It is undoubtedly a most sickening and dangerous phenomenon in Indian politics to-day. But his panacea for the grave evil is undoubtedly of a desperate nature. It is neither practicable nor prudent to divide the country in two warring camps and thus prepare it for a future bloodbath.”

Although Bose did not write these words himself, it is inconceivable that they were written in this leftist mouthpiece without his approval.

Also read: Netaji had vision for economic strength of India, was champion of gender equality: Daughter

Savarkar’s words of praise

Savarkar too, showed admiration and appreciation for Bose wherever he referred to him publicly. About a month after the latter left India, Savarkar sent a message to the organisers of the All-India Subhas day, observed on 23 February 1941, expressing anxiety for his safety: ‘May the gratitude, sympathy and good wishes of the nation be the source of never-failing solace and inspiration to him wherever he happens to be’.

Again, in one of his last interviews with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh mouthpiece Organiser in 1965, out of the four key factors listed by Savarkar that led to India’s independence, three were directly or indirectly linked to Subhas Chandra Bose.

According to Savarkar, “There are many factors, which contributed to the freedom of Bharat. It is wrong to imagine that Congress alone won Independence for Hindusthan. It is equally absurd to think that Non-Cooperation, Charkha and the 1942 Quit India Movement were sorely responsible for the withdrawal of the British power from our country. There were other dynamic and compelling forces, which finally determined the issue of freedom. First, Indian politics was carried to the Army, on whom the British depended entirely to hold down Hindusthan; second, there was a revolt of the Royal Indian Navy and a threat by the Air Force; third, the valiant role of Netaji Subhas Bose and the INA; four, the War of Independence in 1857, which shook the British; five, the terrific sacrifices made by thousands of revolutionaries and patriots in the ranks of the Congress, other groups and parties.”

Chandrachur Ghose is the author of the upcoming biography Bose: The Untold Story of an Inconvenient Nationalist, published by Penguin, is co-founder of Mission Netaji. Ghose is also the co-author of the bestseller Conundrum: Subhas Bose’s Life After Death. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

Also read: Read this before deciding whether Savarkar was a British stooge or strategic nationalist