Lime juice, egg yolk, and sugar topped off with a little nutmeg, poured over rum — tucked away inside a tavern on the island of Antigua, the legendary Captain William Kidd planned his attack over glasses of punch. The day after Christmas in 1688, the idyllic French enclave on Marie-Galante was to become his present to his men. Flying the black flag of the Devil, Kidd’s crew proceeded to help themselves to jewellery, heirlooms, cattle, people, molasses, and clothes.

Kidd’s pirates answered to a simple law: “No prey, no pay.”

Five centuries after the high noon of the pirate kingdoms of the Caribbean, the story isn’t quite over. This time, the world’s largest banks and the international legal system are ensuring the old pirate citadels survive as shelters for super-rich criminals.

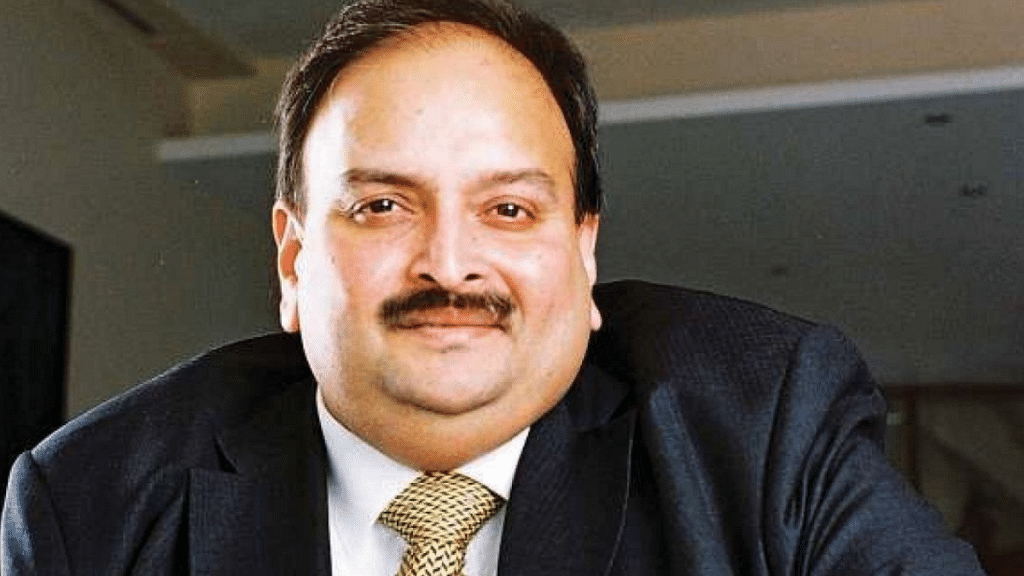

Earlier this week, news broke that diamond magnate Mehul Choksi—alleged to owe a staggering Rs 7,848 crore to banks in India—has been removed from an Interpol watchlist that requires member States to arrest him on sight. The decision followed proceedings brought by Choksi in an Antigua court, claiming to have been kidnapped in a Research & Analysis Wing (R&AW) snatch-plot to bring him back to face trial in India.

The story isn’t extraordinary just because of what happened—but due to the light it casts into a strange world of modern pirate citadels no nation-state seems willing to breach.

Also read: Interpol drops Mehul Choksi from Red Corner list, fugitive diamantaire can now travel freely

The snatch plot that failed

Freewheeling sex was, as a million movies have told us, part of the pirate zeitgeist in the Caribbean. The story, though, has been leached of its startling homoerotic content. “I am not so much in love with any as to goe much abroad,” lamented Margaret Heathcote in a 1655 letter written from Antigua to her brother, the puritan Governor of Connecticut. “They all be a company of sodomites.”

“The Sodom of the Universe,” another contemporary observer of Antigua concurred.

The Choksi story, though, began with a more conventional Caribbean holiday trope. Late on the evening of 23 May 2021, Choksi ambled toward a villa on Antigua’s North Finger, planning to take a young, blonde Hungarian realtor visiting from London to dinner. Then, a police investigation would record, a mask was suddenly put over his head, and the diamond dealer was “tied to a wheelchair and gagged”.

Loaded into a small boat behind the villa his date had rented, Choksi was then transferred to the sea-going yacht Calliope of Arne. Within hours, a chartered Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) business jet was on the ground in Dominica, waiting for Choksi’s extradition.

The story of Choksi’s kidnapping broke on local media, provoking a furore from the political opposition. Following high-profile legal proceedings, Choksi was returned to Antigua—and the CBI had to go home.

Five people present in Antigua during the kidnapping—St Kitts diplomat Gurdeep Bath and United Kingdom residents Barbara Jarabik, Gurmit Singh, Gurjit Bhandal, and Leslie Farrow-Guy—have since been sought for questioning. Earlier this month, documents with ThePrint show, Antigua High Court judge Marissa Robertson ordered further hearings to determine if police in the island nation were effectively investigating the case. Jarabik has since been reported arrested in Abu Dhabi.

Lawyers for Choksi have claimed the R&AW engineered the kidnapping, a claim for which evidence so far is thin. Links between Bath and figures in the Indian political establishment are well-known, though. In 2019, a photograph posted on Bath’s now-private Twitter account even shows him with Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a meeting of the Caribbean Community, an organisation of fifteen States and dependencies throughout the Caribbean.

The flamboyant businessman once painted graffiti over his own luxury car, proclaiming “Range Rover cheats & lies” to make a point. Although Bath was well known to Indian diplomats, there is no evidence he engaged in any wrongdoing.

Evidence on whether the R&AW tried—and failed—to play by pirate rules will have to await criminal investigation. Although kidnappings by nation-states are far from unknown, the finding that India did so could jeopardise its standing as a law-abiding actor in future extradition proceedings.

Get-out-of-jail passports

The reasons why powerful élites in Antigua and Dominica rallied behind Choksi, though, bear careful examination. The businessman had, before fleeing India, acquired Antigua citizenship through the estimated $2 billion “citizenship-by-investment”, or CBI, industry. Founded by St Kitts Prime Minister Denzil Douglas, these schemes offered high net worth individuals a passport that allowed them visa-free travel into over 100 countries, including the United Kingdom and Europe.

Few questions were asked of applicants by companies in the UK and United Arab Emirates that specialised in selling such citizenships, an authoritative investigation by expert Ann Marlowe has reported. In one case, some 5,000 St Kitts passports had to be recalled because they did not even mention the holder’s place of birth.

Lacking resources, countries like Antigua thus extracted rents from their one real asset. In one bizarre case, former Antigua Prime Minister Vere Bird Jr is alleged to have backed a plot by fugitive financier Robert Vesco to buy half of Barbuda, Antigua’s small sister island. This would have allowed Vesco to establish a principality called the Sovereign Order of New Aragon—his own, wholly-owned nation-state.

Elites across the world have been drawn to these pirate islands by their expansive banking secrecy laws — Felons Paul Bilzerian and Roger Ver gave up their United States citizenship for St Kitts. Ross Ulbricht, the founder of the illicit marketplace Silk Road, was seeking to obtain Dominica citizenship when he was arrested in 2013.

Ten years ago, Jatin Mehta, like Choksi, wanted by India for bank fraud, secured a St Kitts passport. The CBI has been seeking without success to establish if he is on the islands.

Antigua’s behaviour was, by the standards of the Caribbean, not unique. Lacking other resources, the States used the international system—in which the sovereignty of all is equal—as a resource. At their core, both citizenship by investment and the region’s secrecy laws serve a single purpose — allowing wealth to evade the reach of nation-states in return for a fee.

Efforts by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to force the Caribbean States into closing their offshore havens were shot down by the George Bush government. The US, economist Vaughn James has written, said it would not cooperate with any global effort to set tax rates.

The fate of pirates

Events ended badly for Captain Kidd, as pirate stories usually do. In the summer of 1701, he was hanged—roaring drunk—at Execution Dock on the Thames in London. For years after, his rotting bones could be seen by all who passed. The pirate had been offered up as a sacrifice by the East India Company to assuage the Mughal emperor Muhi al-Din Muhammad Aurganzeb, who had tired of his treasure ships being plundered.

Later that year, Kidd’s treasure—“gold and silver and some diamonds, rubies and other things”—were auctioned for £5,500. The largest diamond, the so-called Bristol Stone, went for £25. Large parts of Kidd’s reputed treasure were never found.

From the mid-19th century onwards, imperial Britain finally cracked down on piracy globally. The costs piracy imposed on trans-Atlantic trade had become too high to countenance. Local economic interests made the struggle long and often bloody, but pirate derring-do was little in the face of State naval power.

Even though Choksi might have evaded his appointment with Indian courts, there are signs future economic criminals will have a tougher ride. Growing public outrage against tax havens, and the pressures imposed by the pandemic, are likely to push major Western economies to squeeze the pirate States of the Caribbean. The war in Ukraine, moreover, has shown the financial system is increasingly intolerant of oligarchs laundering funds for rogue regimes.

Improbable as it might seem, the portly diamantaire from Mumbai could go down in history as the last pirate of the Caribbean.