It was 9 a.m. on a Wednesday when I received a call from my six-year-old’s school nurse. He’d come to her office and put himself to bed. The nurse reported no temperature and that he was “alert, times three.” His teacher said that he’d seemed discombobulated and not his usual self earlier in the morning. When my son — who isn’t normally a sleepy kid and stopped napping far sooner than I’d have liked — called me after waking, he said, “I was just exhausted.”

It’s not hard to see why. He’s been out of the classroom for the better part of eight months because of Hong Kong’s mandated closures due to Covid-19. Much of what learning he’s had has been through Zoom, punctuated by returns to school that end each time the city deems its infection rate is too high. Children need their routines, and the constant disruption has been highly stressful. Humans usually meet stress with pumping hearts and a fight-or-flight response. Many respond with another coping mechanism: simply falling asleep.

The pandemic is testing us all with volatile, uncertain and complex times, a state familiar to soldiers and firefighters. Our children are going through it, too. The adults in the room worry about their own mental health, job and financial security, avoiding the virus raging around us. That ambient stress is absorbed by our youngest. And keeping them out of school makes it much worse.

One psychologist said to me, “We’ll wonder in a few years, why do some children not have these emotional and social skills?” We’re already getting the answers. The Covid-19 era has lasted long enough for multiple studies to be conducted on the impact for families and children. One thing they show is that social isolation and deprivation are worsening the emotional well-being of young children and adolescents. The impact will be lasting and deepen divisions in society. Test scores are dropping as pupils find it harder to concentrate.

Another thing is that there’s no conclusive, causal relationship between schoolrooms and rising infection rates. Schools reopened this fall for a few weeks, without any large outbreaks, though officials were on alert for an increase in the usual seasonal colds. And yet we’re now in our third round of home learning by Zoom for kids up to the ages of seven and eight. Classroom closures are being extended to older students Wednesday, and follow the shuttering of bars, nightclubs and bathhouses to tamp down a “fourth wave.” (Hong Kong’s infection numbers for the year have been low, about 5,700 cases for a population of 7 million). The latest outbreak is largely due to a cluster of dance club-goers, many of them in their golden years. Or, as another six-year-old put it to me, because “naughty grandmas went dancing.”

Credit to schools for making the best of it. I know teachers and caregivers are put at risk, though there’s evidence to suggest it isn’t so straightforward. But start-stop lockdowns make it tough for children to transition online to offline and back. Classroom habits and independence have suffered. Anecdotally, younger children who would typically start reading around this age aren’t able to pick it up and are losing confidence and interest. Research shows that child development “is a hierarchical process of wiring the brain.” Losing these building blocks impedes future development.

These pressures on children seem a poor way to control the virus. Researchers reviewing studies of school shutdowns to contain epidemics, including severe acute respiratory syndrome and Covid-19, have found very little evidence they’re effective. While some suggested that closures worked as part of a general package of social isolation measures, others indicated the opposite. Closing schools also cuts off access to mental health services.

Shutting down schools during viral outbreaks has better results when transmission is greater in children than adults, unlike the case with Covid-19. One draft study in Crepy-en-Valois in France tracked the virus’ reach. The findings in six elementary schools showed that a total of three children caught it (likely from family members) and attended school while infected. They didn’t seem to pass it to their close contacts.

Almost half of the world’s 1.6 billion primary and secondary students won’t return to school this year, Insights for Education estimates. More than 80% of these live in lower-income countries. In 52 nations across the economic spectrum, Covid-19 infections have actually increased during academic breaks.

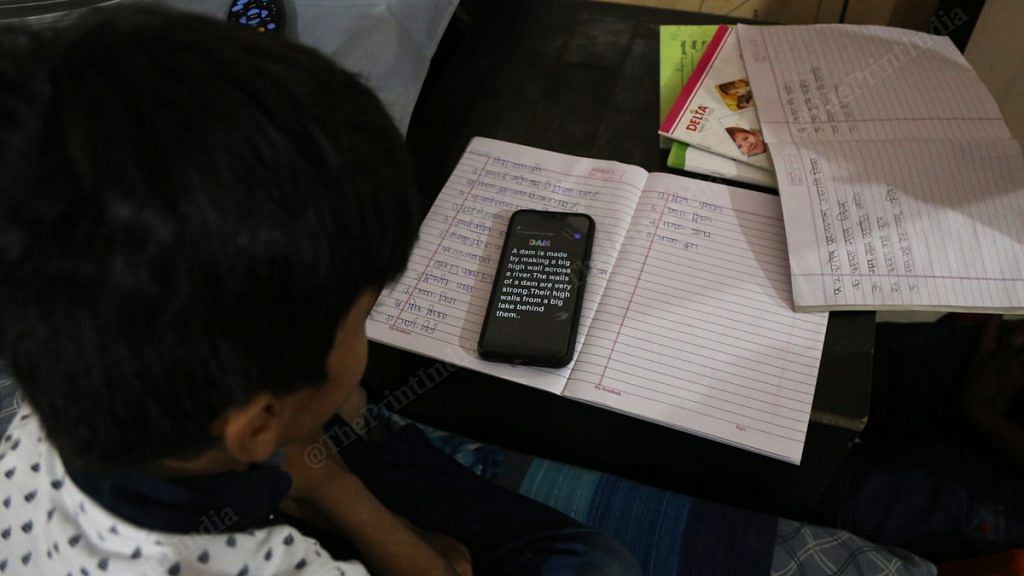

Policy makers also seem to be forgetting other basic guidance to protect children’s well-being. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization say that kids ages two to five shouldn’t have more than an hour of screen time per day. Few households that can afford a screen would be observing such limits in 2020.

“We are driving with the headlights off, and we’ve got kids in the car,” Melinda Buntin, chair of the health policy department at Vanderbilt School of Medicine, told NPR. She’s argued for using precautions like wearing masks and modifying schedules to keep schools open in the U.S. While school districts may not have the resources to fully equip teachers or make big changes to facilities, some in-person instruction should be prioritized, especially for those with disabilities or unable to access remote learning.

History has lessons for how children suffer through trauma like wars and natural disasters. A cratered economy also hurts. A research paper found that during the Great Recession, a 5 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate was correlated with a 35% to 50% increase in “clinically meaningful childhood mental-health problems.” And frankly, we have to account for damage done by stressed-out parents. I am doubtless responsible for part of my son’s anxiety.

The day his school was told classrooms were closing again, he said he was “sad and mad.” In one Zoom lesson last week, he misunderstood his teacher, who’d said they should stretch their legs with a quick walk. He missed half his writing lesson. I was on a work call and heard him outside. Asked why he wasn’t in class, he wasn’t sure, then broke down in tears because he’d “messed up his schedule.” It’s heartbreaking to see and manage. The memes on Instagram tell me I’m not alone.

Sure, children are resilient. But they’re more resilient when they are part of social networks, like parents, grandparents, cousins and friends. They haven’t seen much of those people this year. Yes, there’s the silver lining that I’ve spent so much more time – stressed, happy, grateful – with my children. They’ve also seen much more of their dad, who’s traveling less. As parents, we’ve returned to basics, focusing on reading, communicating and social and emotional learning – partly because there’s no other option. I consider that a win.

Like millions of other children around the world, all my son wants for Christmas is for the virus “to just go away.” I’ll get him some Magna-Tiles, too.-Bloomberg

Also read: Reader View: Virtual classes not feasible in many parts of India, children can lose a year