2021 is now truly over but it will remain an unforgettable year of unmitigated misery. No aspect of human life has remained unscathed from the pall of the coronavirus – from economy to psyche and all things and emotions in between. India, arguably, bucked this trend. No, not as hoped by many who thought India had an exceptional ability to stave off death by this virulent virus due to heat, humidity or innate robustness. But rather by keeping politics and political life central even with Covid. Take, for instance, Britain’s historic moment of high nationalism or Brexit that did indeed occur and happen, yet all chat and political focus remained on the pandemic. Even Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s schedule and diary were scrutinised in terms of the pandemic.

In India, Hindutva trumped coronavirus. Not exactly in saving lives. But Hindutva ensured that its political mastery over the national conversation remained intact. A triumph that concealed the assiduous and century long work that has gone into scripting its success.

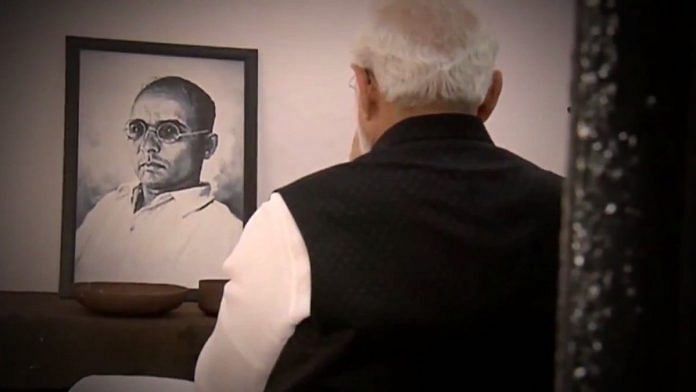

Hindutva – From prison to power

Conceived in prison by its founder Vinayak Savarkar a little shy of a century ago, Hindutva today has full-spectrum domination of Indian life. We all know that Hindutva stands for a militant Hindu First position. Much ink has been spilled on the ideas, makers and shapers of its political pantheon that is the mainstay of best-sellers and especially biographies in Indian publishing today.

Three features from Hindutva’s origins, however, shows that blind fidelity to its first principles could potentially undo Hindutva’s long quest for power. First and foremost, Hindutva undoubtedly emerged in the shadow of Gandhi’s highly visible politics of restraint and nonviolence. It is not simply a question of the Mahatma’s assassin and Nathuram Godse’s political affiliation, which now reappear all too regularly in India’s political discourse. Rather, as twinned and original antagonists, Gandhi and Hindutva pose a particular problem now only for the latter. The father of the nation has indeed done his job and remains immortal. Yet precisely because he has not been completely disowned by Hindutva’s followers, that Gandhi remains a potent presence. A potency that can incite and inform protest as recently seen in the successful farmers’ movement. Gandhi can still indeed instal the meek as the true inheritors of power.

Second, Savarkar’s Hindutva deployed history as the primary vehicle to convey political ideas about India’s future. From Buddhism that was taken as the initial and intimate enemy, which according to Savarkar had militated against the formation of nationality in India, to his well-known antipathy to Muslim rulership and Islam more generally, history was but a site of confrontation. To be sure, Hindutva is the only question in the country today; it is neither metaphysical nor existential but is purely political. Regardless of whether one is Hindu or not, a good one or bad one, a believer or not, Hindutva as conceived by Savarkar sought political mastery over India’s history of mixture and miscegenation.

The hold of the past on the current Narendra Modi government, from aspects of the Neolithic era to the inescapable Jawaharlal Nehru, is very hard to miss. In its current era of political mastery and fulfilment, Hindutva’s main contribution has been in renaming and reformatting history as it unfailingly obsesses with key symbols, monuments and names from India’s past rather than shaping a brave future.

Finally, Hindutva was self-consciously premised on the power of the young male and organised obedience to a central leadership. This has been the metier of not only the RSS but also the myriad political bodies of Hindutva. While disciplined obedience may have charted its path to power, a political culture based on total obedience spells disaster for any potential intellectual capital on which most societies are made today. I don’t mean simply dissent but rather all new knowledge, especially in the last half century, has been essentially disruptive and is based on the ability of the new and/or the young to not only question but to undo their intellectual inheritances. Rewarding obedience might work electorally for a bit but will be far more damaging in every other respect, especially in the cut-throat post-pandemic world economy.

Also read: There’s a crisis in Hindutva politics. It comes from its success

Post-pandemic Hindutva?

Fashioned in secrecy and engulfed by a siege mentality, despite its future orientation, Savarkar’s Hindutva has left little or no instruction on power for its obedient acolytes. And it shows. Analysts of the current government perhaps have rightly focused on the depletion of democracy, dissent and debate in Indian politics. With all due respect, and above all to the most articulate of them all Pratap Bhanu Mehta, the diagnostics such as in his recent article that repeatedly describe Hindutva’s domination and its forms, does not disable it. It simply reinforces that domination as a politics of fear. Crucially, it mistakes surface for depth.

If anything, Hindutva’s desperate and insatiable desire to control the narrative displays its anxious inability to inhabit political power with any degree of comfort. It looks cruel, needy, shrill and on edge. The pandemic has not made Hindutva a more caring and sharing kind of ideology. But it has certainly exposed its saturated ideas of mastery as control.

The author’s new book ‘Violent Fraternity; Indian Political Thought in the Global Age’ is out now with a Penguin South Asia edition. She is Associate Professor of modern Indian history and global political thought at the University of Cambridge. She tweets @shrutikapila. Views are personal.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)