This World Book Day, Jorge Luis Borges’ Library of Babel is real for many Ukrainians. While it doesn’t have infinite labyrinths of adjacent hexagonal rooms or every 410-page book that could ever exist, many libraries in Ukraine have become a sheltered universe away from bombs and shelling, “buzzing like hives”. It has become, as Pharaoh Ramesses II had inscribed over the entrance of his own library, “the house of healing for the soul.”

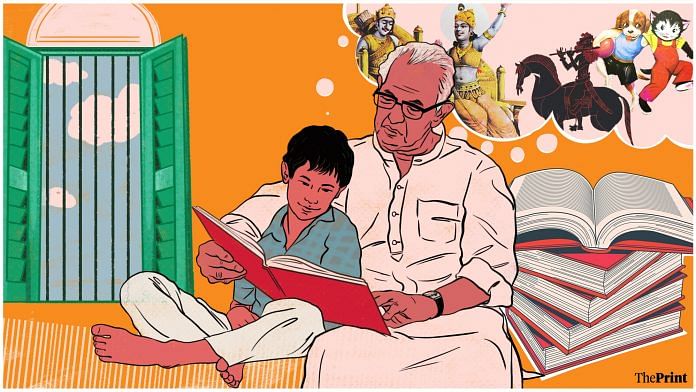

When I think of books, I think of summer in Kolkata. 2001. Perhaps April. Apart from the occasional horn of a lorry that distracts my grandfather, there is no stopping him. One hand holds an illustrated copy of Mahabharata, the arm resting at a right angle, while the other is wrapped gently around my four-year-old body. He dramatises the dialogues. I wait for him to close his eyes, and fall asleep.

I think of the heavy single teakwood bed that has been in our family for four generations. Inside it, a plateau of hardbounds and paperbacks. Books my father never bought me. Bengali letters and browning jackets made out of ancient newspapers and pre-historic calendars hold the pages together. Buried in some corner are cultural hand-me-downs too — a taped-up copy of Tutu-Bhutu and a distinctive blue hardcover of Thakumar Jhuli.

Somewhere Harry Potters hide in plain sight, between science textbooks. After a harrowing parent-teachers’ meeting, a student picks up a surreal-looking Goosebumps at a Scholastic ‘book fair’ at the playground. Books, that won’t ever be returned, are borrowed, and some are hidden away in the memory of former lovers. Great Expectations, The Tell-Tale Heart, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

On Mumbai local train, and Delhi Metro commute, Govindpuris – Jangpuras – Khan Markets – Janpaths pass, with Junot Díaz, Susan Choi and Ben Okri reading Edwidge Danticat, Jennifer Egan and Franz Kafka on The New Yorker Fiction podcast. By the roadside, on foot, vendors hold misprints, imprints, books on a cheap. Books for the living about death, for the dead, about living. There’s something for everyone.

Books are heirlooms, vials of memory, cultural keepsakes. They are symbols of struggle and vitality. They are a sign that the world hasn’t given up on itself.

Also read: A Hindi novel got longlisted for Booker. But at home, authors like Vinod Shukla get pittance

Death of the book?

On the yellow hand-woven garden chair that my grandmother inherited, I once sat, my arms firmly gripping a Philips D8043 cassette player, and listened for hours to the story of Hiru Dakat — the Bengali likeness of Robin Hood. I now notice that audiobooks have existed longer than we realise. Perhaps e-books too.

Decades on decades, we choose to believe a myth. We choose, as if on an impulse to lament the ‘death of books.’ It seems obvious. The touch of mobile screens has replaced the spines of books. Pictures have replaced the printed word. Our reptilian brains, ones that drew before it could conceptualise language, are drawn to moving images again.

But when ‘Meta’ doesn’t mean what it used to a year ago, ‘Amazon’ doesn’t mean what it used to before 1994, why should ‘books’ mean the same for more than a millennium? Our epoch has passed books that have shape-shifted. From audio to pictures to videos. Novels to short stories to flash fiction to #VSS365. Now they manifest themselves within interactive narratives — visual novels. In a world that sees intersections, spectrums and diversity as its touchstones, books, too, have one.

Recently, I rediscovered one of my father’s old books. A three-column newspaper photo of Wetlands that says: “Save East Calcutta To Save The City”, hugs its 40-year-old body. Battered but surviving. It tells me we must take into consideration, now, more than ever, the environmental cost of reading too, and how it changes things going forward.

Also read: Did you get the 36 books you were promised online? I don’t know anyone

An open book

Wandering the streets of West Mambalam, Chennai, in 2019, a few months before Covid-19 would lock us in, I find a happy coincidence a kilometre and a half away — a local government library.

I hurry into the pristine three-storey building. A few people, mostly older than I, sit along the long, reading room table, their faces hidden behind newspapers. In my greed, I glance through the shelves, pick out books I want to read, and hide them in an empty corner. “This is my corner, I’ll come back,” I think. One of the reasons why I still love the city is because of its 162 public libraries — the Anna Centenary Library, its crowning jewel.

Books don’t need saving. The culture around it does. This doesn’t just mean tangible infrastructure like libraries and shops or events like book fairs and literary programmes but the idea that books are the beating heart of a progressive, democratic and harmonious society. It’s the same reason why authoritarian regimes take to book burning or, more recently, people who shun propaganda and want Indians to know about the plight of Kashmiri Pandits recommend reading Rahul Pandita’s Our Moon has Blood Clots than watching The Kashmir Files.

It takes a number of years for ideas and stories to hit the mainstream through television and film. That is why books are always ahead of the game and why writers will never be out of work.

They can show us what is going on now and reflect our fears, desires or yearnings.— Jonny Geller (@JonnyGeller) April 2, 2022

That books are valuable because they foster empathy and understanding, and ‘teach’ you things that might be cliches but true are re-iterated to express the importance of books in human life. However, seldom do people put their weight behind the vagueness of such statements. The truth is there is something too personal about books that, ironically, escape words. No matter if you read books to be understood or to understand. To challenge your intellect or push your boundaries. To escape or thrust deeper into the human condition. This World Book Day, just pick one up.

Views are personal.