The Indian Administrative Service — IAS — a convenient punching bag for politicians from Jawaharlal Nehru to Narendra Modi, is turning out to be the principal resistance force in India’s fight against the coronavirus pandemic.

These IAS officers are not in news. They are not supposed to be. They must work behind the scenes to tackle the public health crisis while their political masters play antakshari or attend wedding ceremonies.

Frontline against coronavirus

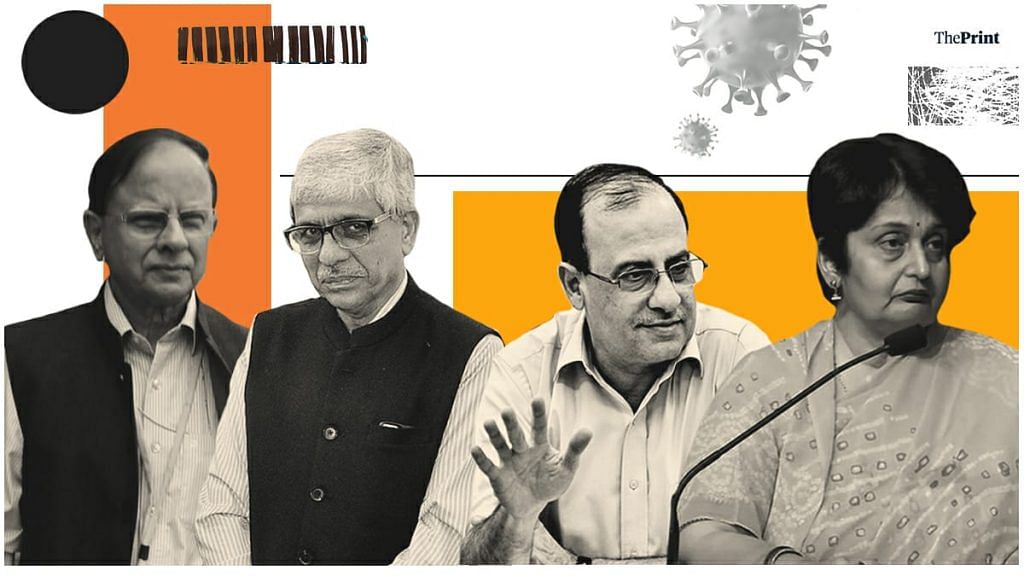

If it is principal secretary to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, P.K. Mishra—assisted by Union health secretary Preeti Sudan who calls up state health secretaries every day—at the Centre, there are many unsung heroes in the states.

In Maharashtra, for instance, Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray along with state health minister Rajesh Tope surprised even their political detractors with their efficiency and dedication in dealing with the coronavirus crisis. People in the know, however, attribute the political leadership’s success to state chief secretary Ajoy Mehta’s stewardship of the administrative response mechanism. Incidentally, Mehta’s six-month extension, given during Devendra Fadnavis’ years, ends in March, and the Thackeray government has now written to the Centre for another extension to the chief secretary.

In Rajasthan, additional chief secretary (medical health and family welfare) Rohit Kumar Singh is at the forefront of Ashok Gehlot government’s fightback against the coronavirus. In Odisha, it’s V. K. Pandian, private secretary to Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik. Odisha was the first state to go for a 40 per cent lockdown following an analysis of the geographical spread of people who came from abroad in March.

Also read: Exams or exercise, it’s all happening inside hostel rooms for IAS and IPS trainees

In Punjab, it’s Suresh Kumar, a retired IAS officer who was appointed special principal secretary to Chief Minister Amarinder Singh. In Karnataka, three IAS officers are leading the fight in their capacity as in-charge of three war rooms — personnel and administrative reforms secretary Munish Moudgil, labour secretary P. Manivannan and Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike commissioner B.H. Anil Kumar. Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, a former ‘Sushasan Babu’, was very late to wake up to the Covid-19 threat but has now constituted a team of senior IAS officers to try to contain the virus’ spread that could spoil his re-election prospects in the October-November assembly elections.

It’s the same story in other states where IAS officers, from secretary to district magistrate levels, are staying on the grind to become the pillars of strength to their chief ministers—as also the Prime Minister at the Centre—who can’t bank on the ministers whose induction in the government was dictated by political compulsions and not by administrative considerations. No wonder, Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman was, last Tuesday, clueless about the composition of the task force headed by her—about a week after the Prime Minister announced it and barely 48 hours before she was entrusted to declare the Rs 1.70 lakh crore economic package for India’s poor. Not many were, therefore, surprised when she evaded repeated questions about where this money would come from.

Most of the ministers even at the Centre spend most of their time tweeting and retweeting every word of PM Modi and works of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), while bureaucrats sweat it out trying to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Not that these ministers were doing a great job before the virus arrived in India. When was the last time you heard telecom minister Ravi Shankar Prasad speak about the AGR crisis in the telecom sector? Or about the sufferings of thousands of MTNL/BSNL consumers due to their services crashing?

As India witnesses the sad spectacle of thousands of migrant daily wagers and labourers trudging for hundreds of kilometres to try and reach home, try recalling the name of the labour minister. You may have a degree in mnemonics if you remember it. He is Santosh Kumar Gangwar, minister of state (independent charge), Ministry of Labour and Employment. By the way, last week, he did issue an advisory to all states to transfer money into the accounts of construction workers. Nothing more, nothing less.

Also read: This is the team advising PM Modi in India’s battle against coronavirus

Comeback of the IAS officers

When Narendra Modi took over the reins of the country in May 2014, IAS officers were largely happy. They were no less fed up with the policy paralysis during the latter part of the UPA-II government. And they were thrilled when they saw the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) calling them up directly, with ministers signing on dotted lines on the files without a whimper. Many others (including yours truly) thought it was a good move, given the massive talent deficit in Modi’s ministerial team. The dream run was, however, short-lived.

The bureaucracy soon realised that the new government put a premium on loyalty, and not talent.

It was different in Nehru’s case. As Ramachandra Guha writes in India After Gandhi, there was a time when Nehru had “little but scorn for the bureaucracy” and wrote in his autobiography that few things were more striking in India “than the progressive deterioration, moral and intellectual, of the higher services, more especially the Indian Civil Services”. But that was 12 years before India’s Independence when these services were instrumental in putting freedom fighters in the jails. As Guha points out, 16 years after he wrote that, Nehru entrusted the same bureaucracy—and chief election commissioner Sukumar Sen, an ICS officer—with the gigantic task of holding the first elections in Independent India, comprising mostly illiterate voters. India’s first prime minister’s views had to have changed after its success.

Also read: To break IAS grip, Modi govt is picking more non-IAS officers for top jobs

Time for a re-think

The Narendra Modi government has, however, gone about undermining the IAS, chipping away its exclusive rights and privileges one by one. First, it was the introduction of the 360-degree appraisal system for empanelment of bureaucrats at the joint secretary level at the Centre and then for their promotions. Their annual confidential reports (ACRs) were no longer the main factor. What mattered was the ‘feedback’, ostensibly from a bureaucrat’s seniors, peers, juniors and even those outside the service—essentially, and practically, to determine the political leanings and loyalty of the candidate under consideration.

In subsequent months and years, the IAS fraternity saw other alarming signs—lateral entry of professionals into the government as joint secretaries, attempt to change recruitment rules, forced resignations by senior bureaucrats, misbehaviour by ministers with senior officers, et al. It was no solace to IAS officers that officers of the Indian Police Service or other civil services found the going equally tough.

That’s the reason not many IAS officers are very keen on coming to Delhi on deputation; many sought and got repatriation to their home cadres, on one pretext or the other.

It is in this backdrop that the coronavirus has revalidated the strength and relevance of India’s steel frame—the IAS. For one IAS officer who might have hit the headlines for evading quarantine orders in Kerala, there are thousands of others who are working day and night in offices, risking their own lives to protect people. Once the novel coronavirus is beaten back, Modi government may like to re-think its understanding and definition of a committed bureaucracy.

Views are personal.