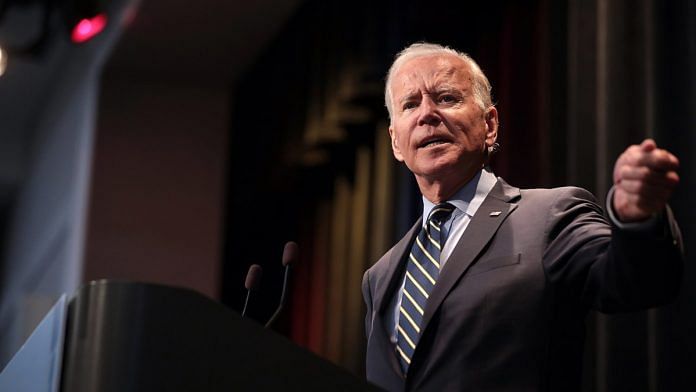

With the May Day deadline looming for a complete withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan, President Joe Biden faces his first tough foreign policy decision. There are no good or easy options.

Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin has promised there would be no “hasty or disorderly withdrawal” that puts US and NATO forces at risk, no matter what the outcome of the current policy review. He also stressed that more progress was needed in the intra-Afghan dialogue accompanied by a reduction in violence. US commanders have the “right and responsibility to defend themselves and their Afghan partners against attacks,” he said last week.

The signal from the US is clear — the 1 May deadline is not etched in stone. That means a possible delay in the timetable for the departure of the remaining 2,500 US troops and about 5,000 from NATO countries. The extension will have to be negotiated, which means Pakistan will once again come centre stage.

Also read: Why Biden’s ‘America is back’ is not good for the world’s ‘China concerns’

Army Chief General Qamar Bajwa has already named his price for the intervention. He apparently told US CENTCOM Commander General Kenneth McKenzie Jr. that Secretary of State Antony Blinken should call Taliban leaders to request a deadline extension. Bajwa’s aim is legitimisation of the Taliban with the new administration, raising Pakistan’s clout while keeping the Afghan government on the sidelines.

As for India, New Delhi has long been concerned about the arbitrary deadline, even while accepting the reality of an eventual US exit. It has watched Taliban’s continuing attacks on Afghan security forces and civil society leaders in Afghanistan with alarm. What was supposed to be a conditions-based withdrawal became a plain exit strategy in the last days of the Trump Administration as thousands of US troops left in December and January.

But the Taliban haven’t held up their side of the bargain — the intra-Afghan dialogue is stuck and a ceasefire is nowhere in sight. The most important US demand that Taliban cut ties with al-Qaeda is caught between what’s in the written agreement and what might have been verbally agreed to in terms of “assurances and understandings.” US Special Representative, Zalmay Khalilzad, is the only person who truly knows — he conducted several one-on-one meetings with Taliban leaders in Pashto with no note-takers.

Under the deal he crafted, the US committed to 10 clear actions, including a complete withdrawal of troops by 1 May. While most of the US commitments are either partly or fully verifiable, the Taliban’s promises are unclear and subjective, according to Jonathan Schroden, a military operations analyst and an Afghanistan expert.

The most important Taliban commitment of not allowing terrorist groups to use the “soil” of Afghanistan to threaten the security of the US or its allies is highly subjective and cannot be verified, he says. Of the seven commitments Taliban made, only one is objectively and publicly verifiable.

Usually, the Americans craft agreements that weigh heavily in their favour but the Afghan peace agreement is clearly not one of them. Some US experts have suggested a six-month extension, which, at first, seems too short. The idea is to recalibrate the entire peace agreement with the US, using removal of UN sanctions and release of Taliban prisoners as leverage. The Taliban want international legitimacy and have long demanded lifting of UN sanctions.

Taliban leader, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, threw down the gauntlet last week. In an open letter addressed to the American people, he urged the US “to remain committed to the full implementation of the accord.” He went on to repeat the many Taliban propaganda points to buttress his case: A majority of the Afghan people support the “Islamic Emirate,” rights of women will be granted as per Islamic law (whatever that might mean), and the Taliban will curb poppy cultivation.

There’s no question that a delay in US withdrawal would have to be negotiated because a unilateral announcement from Washington would amount to abrogating the deal and open western forces to Taliban attacks. Biden Administration’s policy review is expected to be completed this week after which Khalilzad is expected to travel to Doha, Islamabad, and possibly New Delhi.

Hard-nosed analysts who want to end America’s longest war say that the Biden Administration must focus only on the main outcome it wants. The real question has to be about Taliban breaking their links with al-Qaeda. Can US negotiators get the Taliban to publicly sever connections and find a way to hold them accountable? Continued presence of US troops will not help guarantee the rights of women, they say.

Others are displaying a certain kind of fatalism — the government of President Ashraf Ghani “may be too corrupt and fragile to survive” no matter what the US chooses to do. The Taliban will continue attacks because they believe victory is near regardless of any change in the deadline. This is nothing but throwing the Ghani government under the bus.

Also read: Why the idea of a US-Pakistan ‘reset’ is good for policy papers, but not policy

As an observer of the region wryly noted, if other “corrupt and fragile” governments — there are some right in the neighbourhood — can survive, so can Ghani’s. The Afghans fought the Taliban before 9/11 without much help and they will fight them again and this time they are better prepared.

Meanwhile, the situation on the ground is dire. The Taliban have refrained from attacking US and NATO troops, but they are relentlessly targeting Afghan security forces, women judges and journalists, NGOs, and government workers in a campaign of assassinations to systematically break down the pillars of civil society built over the last two decades.

Pakistan and its friends in Washington are busy discouraging the idea of reopening and renegotiating the peace agreement. They want the Biden Administration to look forward, not back, and put its energies on pushing the intra-Afghan dialogue. This gives Rawalpindi the edge since the Taliban are living, training, receiving arms and getting healthcare from Pakistan.

Seema Sirohi @seemasirohi is a columnist based in Washington DC. She writes on US foreign policy in relation to South Asia. Seema has worked with several Indian newspapers over the last three decades. Views are personal.

The article first appeared on the Observer Research Foundation website.