The number of pending cases in India’s higher judiciary and the number of vacancies in the Supreme Court and the high courts have been simultaneously increasing. The number of pending cases, which is directly related to the judge-to-population ratio, is an important tool to understand the justice delivery system in a democracy. So, it becomes pertinent to analyse the current status of vacancy in India’s higher judiciary, in general, and high courts, in particular.

There are many possible causes for the vacancies but the collegium system is especially to blame.

Vacancy of judges in SC and HCs

The Department of Justice under the Ministry of Law and Justice releases monthly statistical data about the vacancies of judges in the Supreme Court and the high courts. The data released on 1 October 2020 reveals that the Supreme Court has a sanctioned strength of 34 judges, out of which four posts are currently vacant. These four vacancies are due to the retirement of Justices Ranjan Gogoi, Deepak Gupta, R. Bhanumathi and Arun Mishra. The Supreme Court collegium responsible for making recommendations for filling these vacancies has not made any since Chief Justice S.A. Bobde took charge in November 2019.

The current vacancy status in the 25 high courts of India reveals that out of 1,079 sanctioned judges’ posts, which include both permanent as well as additional judges, 404 posts (approximately 37.44 per cent) are vacant. Besides, three high courts – Gauhati, Madhya Pradesh and Uttarakhand – also have acting chief justices. These vacancies in high courts have come about due to the retirement, resignation, demise and elevation of judges.

Further dissection of these high court vacancies gives a more nuanced understanding. Table-1 provides the ranking of the high courts that have a vacancy of more than one-third of their sanctioned strength. Twelve high courts are functioning with less than two-thirds of their sanctioned strength and out of which, three high courts – Patna, Rajasthan and Calcutta – have more than 50 per cent vacancy. The Patna High Court is at the top of the list with 56.6 per cent vacancy. This is a cause for worry because Bihar is the third-most populous state of India, as per the 2011 Census.

Further analysis of the Supreme Court collegium resolutions reveals that the last recommendation for the appointment of a judge in the Patna High Court was made on 1 April 2019. Since then, judges have been transferred from this high court but no fresh appointments have been made. It is surprising to see that the high court in the home state of Ravi Shankar Prasad, the Union Law Minister, has the highest vacancy with not a single appointment in over 18 months.

Also read: Supreme Court collegium meets after 4 months, to fast-track appointment of high court judges

Trends in vacancies

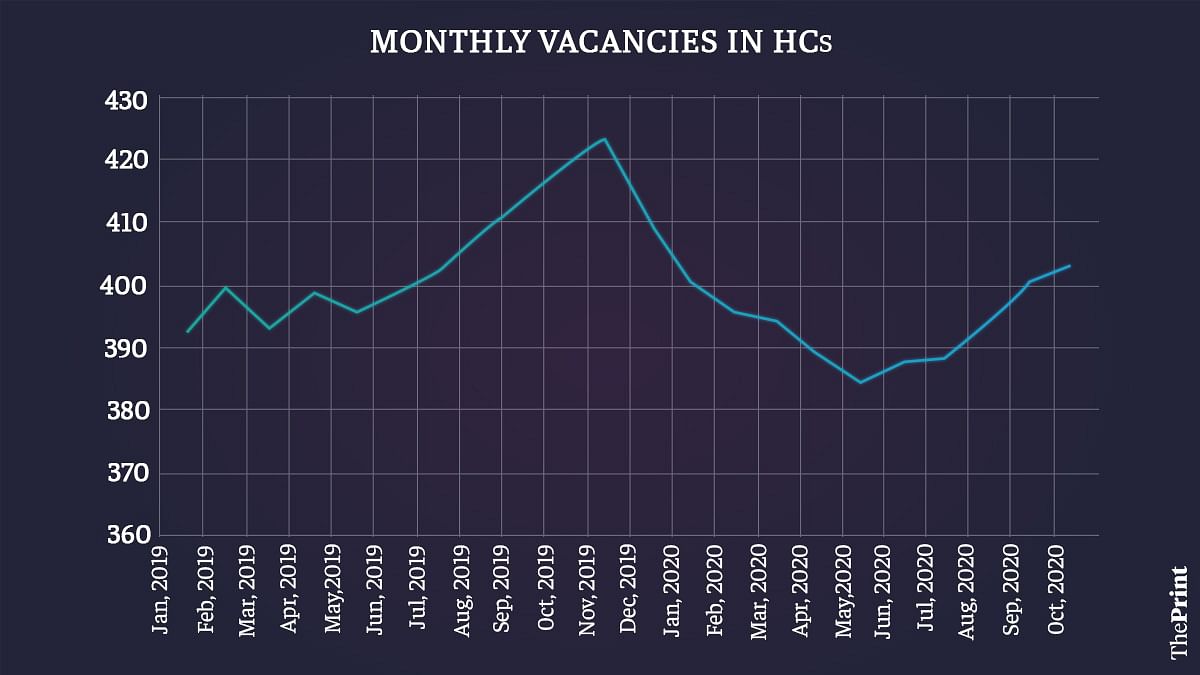

Two major trends can be seen from the aggregation of available data from the website of the Department of Justice about vacancies in all high courts from January 2019 to October 2020. First, there has been a marginal decline in overall vacancies since Chief Justice Bobde assumed charge in November 2019, but after the Covid-induced lockdown, vacancies have started increasing again. Also, the number of acting chief justices in high courts has declined in his tenure. Second, throughout this period, there has been a continuous vacancy of more than one-third posts in the high courts. We do not have data prior to January 2019.

The continuous vacancy of more than one-third of sanctioned posts is a worrying trend when it comes to the administration of justice in India.

Furthermore, Graph 1 indicates that the vacancies in high courts start increasing when the tenure of the Chief Justice of India reaches its end. One could infer that the CJIs are reluctant to push for the appointment of judges towards the end of their tenure. The reasons for this are unknown.

Also read: Judge vacancies high, but Modi govt returns dozen names to SC collegium for ‘reconsideration’

Responsibility for filling vacancies

The appointment of judges in high courts happens through a Memorandum of Procedure (MoP), under which the chief justice of the concerned high court sends a proposal with the name of the person being considered for the position after consulting with his/her two senior-most colleagues. Under Clause 14 of the MoP, the chief minister of a state can also send a name to the chief justice for consideration. The final proposal is sent to the Centre through the governor, but only after the chief justice has the written opinion of the chief minister. The Ministry of Law and Justice sends the proposal to the Chief Justice of India after necessary background checks. The CJI, after consulting with his two senior-most colleagues and a colleague familiar with the functioning of the concerned high court, makes the recommendation. The proposal is then sent to the President by the Prime Minister for approval. The President of India issues a warrant of appointment under Article 217 of the Constitution.

Since the proposal is sent first to the Union government, it has been argued that there has been undue delay in clearing names. There is also the argument that the government sometimes deliberately delays clearing the proposal.

Ever since the Narendra Modi government came to power in 2014, it has been alleged that the Centre has been obstructing the appointment of judges in the Supreme Court and high courts. Since 2014, it has been reported many times that the Modi government and the collegium were not on the same page over the appointment of judges. Such cases are often framed as the obstruction of the executive in judicial appointments, but many cases also arise due to the adverse report of intelligence departments.

Attorney General K.K. Venugopal recently told a bench of the Supreme Court led by Justices S.K. Kaul and K.M. Joseph that the vacancies in the high courts are not because of delays caused by the Union government but the collegium of high courts since the latter has not been sending proposals for appointment within the stipulated time period. The submission of the Attorney General with the data analysis of vacancies indicates that the high court collegiums are not working properly, and administration of justice is getting jeopardised. Both the Union government and the Supreme Court collegium need to rethink the existing procedure of appointment.

The author is a PhD Scholar at the Department of Politics & IRs, School of Law and Social Sciences, Royal Holloway, University of London (@arvind_kumar__). Views are personal.