For long, India’s Hindi film industry has depicted caste realities by coating it with the rich versus poor narrative. Dalit cinema has been hitting against this narrative every year with honest films about caste. 2021 was similarly a good year for Dalit cinema with films such as Jai Bhim, Jayanti, Uppena, Karnan, Sarpatta Parambarai. But the question over missing Pasmanda characters remains.

Over the past year years, the onscreen presence of Muslim characters has increased amid rampant distortion of historical facts. Sadly, most filmmakers have been able to locate foreign Muslim invaders but have remained oblivious to India’s indigenous Pasmanda Muslims who have been systemically marginalised. It’s true that movies are made with the intention of earning profits, but the fact that filmmakers and writers have only been able to feature Ashraaf as central characters shows their upper caste bias.

In this article, we will discuss films based on four principal types of Muslim identities to illustrate how the Hindi cinema has made Pasmanda society completely invisible by ignoring it from the storyline.

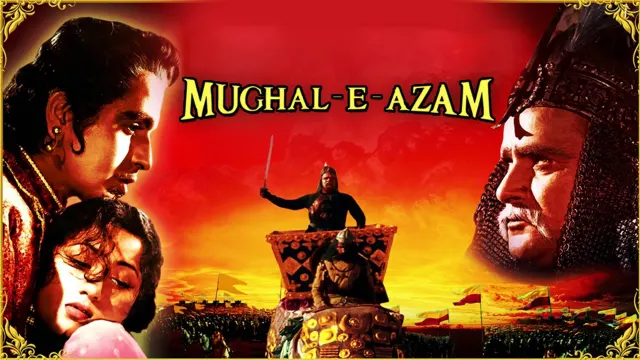

The first category of films include those that have shown Ashraaf culture and their etiquette as the norm in Muslim society. The mannerism and language of Ashraaf in movies such as Mehboob Ki Mehndi, Pakeezah, and Umrao Jaan were shown as ‘Muslim culture’. In reality, the elegance and etiquette shown in such films have nothing to do with the 85% Muslims belonging to the Pasmanda society. In Mughal-e-Azam, Akbar is shown as being proud of his Timur lineage and this fact is repeatedly featured in the movie. Yet, by not identifying the caste/lineage of ‘Anarkali’, the film’s narrative turned into an ‘entitled versus impoverished’ saga.

Ashraaf writers have always denied casteism in Muslim society. At the cost of not permitting caste consciousness of the Pasmanda society to develop, they chose to extol the Ashraaf culture in the Hindi cinematic world.

The second category of films without Pasmanda characters include those that portray the storyline of the protagonists from different religions falling in love with each other. Movies like Roza, Bombay, Ishaqzaade, Zubaida, etc are some examples. No matter how much the propaganda of ‘love jihad’ is spread, it is of no coincidence that most of these films feature female lead as Muslim and male lead as Hindu.

“In a semi-feudal society like India, a woman is always identified along with her husband, that is, if the boy/husband comes from a Hindu family, then his children will also be considered as Hindu. In this way, these matrimonial relations are seen as establishing one’s own superiority and triumph over the other religion rather than as a mutual love affair between people belonging to two sects,” writes film critic Jawaharmal Parikh. One cannot imagine seeing a Syed girl and a Halalkhor (Muslim sweeper) in a relationship on the big screen. In Muslim society, if a Syed girl marries a Pasmanda boy, then even the Muftis of big seminaries (madrasas) like Deoband would annul such marriages by terming them un-Islamic. On the other hand, in films like Masaan, Sairat, etc., love for a Dalit boy is a simple social fact, which has been shown quite beautifully on the screen. Films are often termed as the mirror image of the society, then in such a big exhibition of art, will the Pasmanda society ever be able to witness its own truth being presented with complete honesty?

In the third category, the storyline is based on terrorism. In the 1980s, films such as Subhash Ghai’s Karma or Mehul Kumar’s Tiranga didn’t link terrorism with any religion. But later on, the issue of terrorism was consistently portrayed as a proxy war waged by Pakistan in films such as Roja, Sarfarosh, Dil se, Ma Tujhe Salaam, Jaal etc. Post 9/11, terrorism has been clearly linked with Islam. In films like Fanaa, Dhokha, Mukhbir, Aamir, A Wednesday, etc., not only terrorism had a religion but it was internationalised too. In this way, these films served to create a perception that ‘not every Muslim is a terrorist but every terrorist is a Muslim.’

Another fact is that most of the terrorist organizations are headed by Syeds or other upper caste figures who desperately need Pasmanda’s head as a sacrificial lamb. Every such film earns loads of accolade by targeting terrorism, but they also confine the Pasmanda society in a cell of hatred where they serve a life imprisonment sentence. Kashmir is a classical example of the caste-based character of terrorism in India. All top separatist/terrorist organizations like United Jihad, Jamaat-Islami, Hurriyat Conference etc. are under the firm control of Syeds. It would not be wrong to say that the entire Kashmiri administration is under the iron grip of the Syeds, but during the entire spate of insurgency against India, very few Ashraf families and very few [Syeds] have laid their lives, while the Pasmanda castes have suffered the most due to this large-scale insurgency..

The fourth category of stories – as narrated in films like Tamas, Pinjar, Gadar – Ek Prem Katha, Garam Hawa, Dev, Hey Ram, etc – have tried to depict the tragedy of communal riots that took place during the Partition era. An attempt has also been made to touch the human aspects amid the riots. But, even in these films, communalism is depicted as a direct fight between two religions. The Pasmanda movement stands on the fact that in order to understand the prevalence of communalism in India, it will not be appropriate to look at it only through the prism of religion, instead the trend of communalism in India can be better understood from the perspective of caste. Will it be wrong to say that Jinnah and the entire Muslim League were a party of Ashraaf Zamindars/upper caste Muslims who facilitated country’s division for their own class-caste based interests?

On the other hand, Pasmanadas of that time were opposing the Two Nation Theory through their contemporary organizations like ‘Momin Conference’. Some Ashraaf Congress leaders like Maulana Azad were only representing their party Congress, so they remained on the Congress side, even on the issue of partition. The founder of Momin Conference, Asim Bihari, had categorically opposed the creation of Pakistan till the very end. He had said, “Wherever a true believer (of Islam) lives, his Pakistan (holy place) is in that land only, we don’t need any Pakistan.” Every such story in Hindi cinema will be far from the truth without presenting Pasmandas’ side.

Now let’s talk about films like Bombay, Parzania, Firaq, Kai Po Che, Zakhm, Fiza, etc that are based on the post-independence communal riots. Why don’t our secular liberal intellectuals take up this question that only the Ashraaf castes are real beneficiary of Muslim communalism? The (so-called) Muslim leaders always remain assertive on emotional issues like Shariat, Burqa, Aligarh, Urdu but they never raise their voice against the structure of the anti-poor political system. If any filmmaker dares to show this real character of Ashraaf leaders and their Muslim politics, then they are promptly accused of spreading ‘Islamophobia’. Even the Pasmanda don’t address their problems and start rallying behind the issues that serve the interests of Ashraaf politics.

Despite all these arguments, we need hope more than criticism. The way Dalit cinema is candidly and quite aesthetically conveying the Dalit, Bahujan, Tribal lifestyle and values to the people through the medium of art, and is openly raising questions related to their problems, it feels like a catalyst for the Pasmanda society too. Movies do affect society, so it is necessary that we play the character of an audience with maturity and accountability. After all, it is the society that decides who will influence the films and who will not.

Abdullah Mansoor is a Pasmanda activist and an educator and runs the YouTube channel Pasmanda DEMOcracy. Views are personal.

This article has been translated from Hindi by Ram Lal Khanna and edited by Prashant.