Once the embodiment of journalistic cool, the star editor and political acrobat now stands exposed by a series of brave women for being a sexual predator and serial aggressor.

Moral ambiguity. Ideological slipperiness. Political expediency.

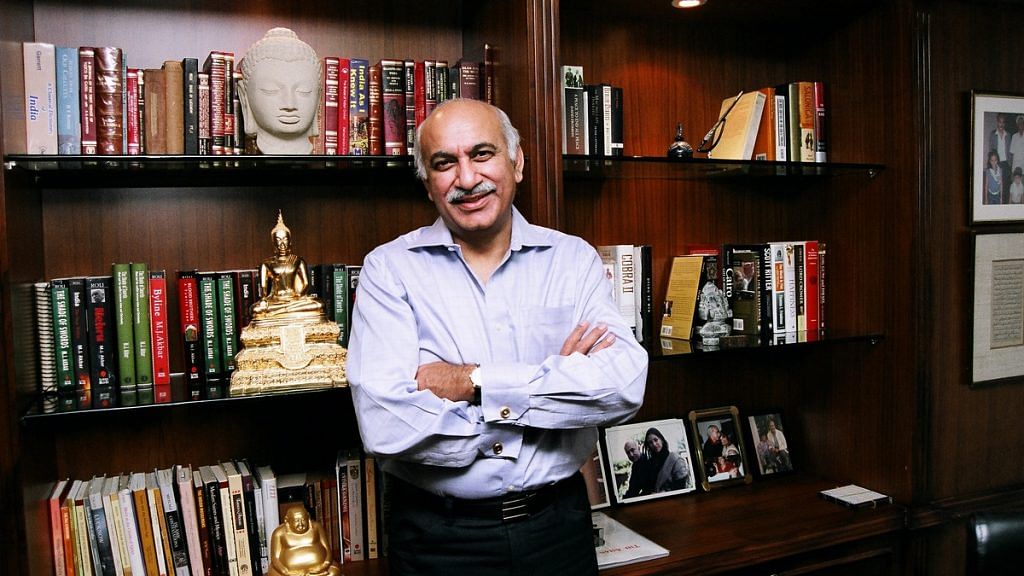

Much before he became a byword for sexual harassment, Mobashar Jawed Akbar, once of Telinipara, West Bengal, and now a suave inhabitant of Lutyens’ Delhi, was a master of all three dodgy attributes. In a career dotted with several firsts, he was editor of a fortnightly news magazine at 23, a weekly magazine at 25, launched The Telegraph in 1982 putting Calcutta as it was then on the national journalism map, anchored Doordarshan’s first private news magazine Newsline in 1985, started an ambitious multi-edition newspaper with a series of dubious businessmen who fell from grace before he did, and worked with two prime ministers, Rajiv Gandhi and Narendra Modi, who were as different politically as they are personally. But for a man so conscious of his perceived place in history that he authored his own family saga for posterity, Blood Brothers, he will be remembered for just one thing — being the nation’s most high-profile serial sexual predator.

Rightly so, with an unrivalled outpouring of long-withheld rage at his sense of entitlement. In account after searing account in what is being called India’s #MeToo moment, women have talked with extraordinary courage and clarity of being groped and forcibly kissed, being met for interviews clad variously in a bathrobe or in underwear, being encouraged to drink in his presence and being stared at suggestively. He has responded with a singular lack of empathy by accusing them of being part of a conspiracy to destabilise the government, a charge so ridiculous that it has been met with even greater revulsion. On 17 October, 10 days after the first piece by senior journalist Priya Ramani named him, he finally announced he would resign as minister of state for external affairs but not before reiterating that he would fight the accusation in court, in his personal capacity, armed with the legal services of an established firm with 97 lawyers on its roster.

For a man so particular about optics, of ensuring the perfect headline for just the right picture, it doesn’t just look bad. It is bad. What makes Akbar the poster boy for toxic masculinity; the epitome of a tone-deaf culture that is stale, male, and fail; the kind of man who can live in the 21st century and not know that no means no; the president of the nudge-nudge, wink-wink old boys’ club of which Tarun Tejpal is an honorary member; and the very embodiment of an aggressive and regressive patriarchy that is enraging women around the world?

Also read: India’s foreign office could not afford a man like MJ Akbar: Nirupama Rao

In short, just who is M.J. Akbar? He’s the son of a jute mill labour contractor who wouldn’t take no for an answer till his son, whom he considered extraordinarily gifted in English, would get admission to Calcutta Boys’ School, the only posh school that had not rejected his efforts outright. He’s the precocious teenager who was “never short of ambition”, writing a stunning account of Mother Teresa’s relief work in Ranchi for Desmond Doig’s Junior Statesman (better known as JS). He’s the English undergraduate student of Presidency College who wasn’t allowed to stay in the hostel because he was a Muslim. He’s the tough talking, hard drinking editor who could make grown men tremble with a few carefully calibrated strikes of his pen. He’s also the author of 10 books, among them a well-regarded biography of Jawaharlal Nehru and a popular history of Pakistan.

In his own words in the largely autobiographical 2006 novel, Blood Brothers, he is a “seamless chameleon”. Indeed, he was a Bihari in Telinipara and later when he fought his first Lok Sabha election in Kishanganj in 1989, defeating Syed Shahabuddin. He was a Kashmiri from his mother’s side when he went to Lahore. He was a self-styled Bengali bhadralok when he went to work at Ananda Bazaar Patrika. He was a pucca little Englishman eating cucumber sandwiches and devouring Readers’ Digest condensed books with his father’s sahibs, Simon and Matthew, within the confines of Victoria Jute Mill. And he was a proud secularist, the son of a man who returned from a brief stay in Pakistan after Partition because “there were too many Muslims there”.

English was his passport out of Telinipara and into the world of bright-eyed, bushy-tailed trainees who worked with Khushwant Singh at The Illustrated Weekly of India in 1970 and 1971. As Akbar wrote in an obituary of his mentor in The Times of India in 2014: “Khushwant Singh believed in the young, and in young journalists, to an extent that would have been remarkable in any age, but was positively insurrectionist in 1970 and 1971. The media hierarchy left those on the first rung of the ladder scratching around for years. Khushwant lifted them to the top with a carefree shrug, but with a very, very careful eye on the copy they submitted. I have no idea what life would have had in store for me if Khushwant, and his wonderful deputy editor Fatima Zakaria, had not offered me the chance that changed my fortunes. But this I do know: what they did was enough to command a lifetime’s gratitude.” And a series of successes that possibly watered and fed an incipient God complex.

Also read: ‘Relationship based on coercion not consensual’: Pallavi Gogoi hits back at MJ Akbar

It came from a firm belief in his own self-worth, which was burnished by his days at Sunday and The Telegraph when he was part of a new kind of typewriter guerrilla who dragged journalism out of its staid confines. S.N.M Abdi, who was 20 when he was hired by Akbar as a sub-editor-cum-reporter in Sunday, wrote this in Outlook in 2015: “I’m yet to see another editor work as hard. He came to office even on Sundays. But he didn’t have much faith in subbing (sub-editing); he rewrote stories from top to bottom. Sometimes he rewrote half a dozen 1,000-1,500-word magazine stories in a single day, pounding away at his Olivetti typewriter in those pre-computer days. Like income tax, Akbar was a great leveller; he rewrote everyone’s copy—from assistant editors’ to mine—in his inimitable style. In the bargain, some of us managed to learn the craft of writing—a professional skill I have used for over three decades to earn a decent living.”

It is something Tavleen Singh, who has written quite contemptuously of his tendency to court the powerful, endorses. As she wrote in an email response to me: “Akbar is no friend of mine. But, I believe it is wrong not to remember that Akbar was the first editor in India to allow women to report on everything from coups, wars, elections to politics and government. I spoke up for him because when as a single mother I returned to journalism after an absence of two years he gave me a job instantly. The entire Delhi bureau of The Telegraph was made up of women. When I asked him why this was (so), he said he hired on merit.” She also makes the point in her book, Durbar, that he could be difficult to work with: often playing favourites, burying scoops inside if they didn’t belong to him and ignoring political realities even if they were staring everyone in the face.

Also read: The women who are not for #Metoo in India

Yet, that was also perhaps when Akbar was at the peak of his professional prowess. His decision to switch to politics in 1989, after being so censorious of it, was the point where even his greatest loyalists started to see him for what he was becoming: an opportunist who would go on to compare Modi to Hitler in 2002 in Asian Age (“In Hitler’s case, the enemy was the Jew; in Modi’s case the enemy is the Muslim”) only to write in March 2014 in The Economic Times that for India, “there is only one way forward. … You know his name as well as I do”. In a letter dated 29 October 1989, typically handwritten on lined paper, addressed to The Telegraph team, explaining his decision to quit to fight elections in Kishanganj, he dresses it up well: “There comes a moment in life when we have to stand up and face evil directly, irrespective of the consequences. It is going to be very difficult. I have no illusions about that. Bihar is aflame and there are no assurances left. But I could not have run away from this fire. The flames have in a sense been becoming me, and I must do what little I can to help bring some sanity back to our nation. Look at the faces of children and you will see why I feel so driven.”

He did win Kishanganj but Rajiv Gandhi lost, and eventually two years later was assassinated. When Akbar fought the next elections in 1991, he lost, and soon quit the party. Rasheed Kidwai who worked with him in Asian Age between 1993 and 1996 says Akbar always felt he was better than most politicians, more erudite and better read, but also with a lower tolerance for the nonsense that politics begets. And unlike other journalists who had dabbled in politics, from Kuldip Nayar to Khushwant Singh, he could never recover his journalistic stature. The franchisee model of Asian Age saw him join hands with a string of tainted or debt-ridden associates, undertrial politician Suresh Kalmadi, financier Ketan Somaia, willful defaulter Vijay Mallya and Deccan Chronicle‘s T. Venkattram Reddy, which he believes only added to his disillusionment.

Sacked from Asian Age in 2008, he continued as a journalist, starting and shutting down a news magazine, Covert; a Sunday newspaper The Sunday Guardian with old friend Ram Jethmalani; and becoming editorial director of India Today. But his heart was clearly elsewhere and no one was surprised to see him quickly switch his loyalties from L.K. Advani — who made him a member of his informal Pandara Park club — to Modi, just in time to see him become Prime Minister in 2014. The man who urged an entire generation of men and women to thumb its nose at hidebound institutions had become the worst kind of establishmentarian himself, craving to be an insider, no matter how high the cost of re-entry.

Also read: It was consensual: Akbar denies rape charge, wife says US journalist Pallavi Gogoi is lying

At 67, Akbar is grandfather to three children, and has what seems to be a wonderful relationship with his wife of 43 years, whom he met as a trainee at The Illustrated Weekly of India. As he faces his accusers, he will have ample time to contemplate the words of his favourite song, his caller tune for the longest time, from Hum Dono, starring his iconic movie hero, Dev Anand: Main zindagi ka saath nibhata chala gaya/har fikr ko dhuan main udata chala gaya/barbadiyon ka shok manana fizool tha/barbadiyon ka jashan manata chala gaya.

When and if the serious charges of mental and physical abuse against him are proven, he will not be the only person celebrating his barbadi (ruin).

The writer is a senior journalist who worked with M.J. Akbar at India Today. She was Editor of India Today between 2011 and 2014.

Catch ThePrint’s extensive, in-depth coverage of the #MeToo movement.