Locked in my two-room house for the past 40 days, I stand daily near my window smiling at the sunlight, and appreciating the rare blue skies of Delhi.

Much like the rest of the world that finds itself in an unprecedented lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic, I too struggle to make sense of this isolation and silence.

But this isn’t my first time.

I have looked outside to find life in the past as well. Not through a window, but through bars, outside my solitary confinement ward in Delhi’s Tihar Central Jail. The past one-and-a-half months have been a replay of the memories of my 14 years in three different jails.

Since the declaration of lockdown, I have come across several people comparing their experiences of being confined in their homes to ‘prison’. “It feels like a prison”, “When will we be free and be able to meet our friends and family again”, “I feel suffocated in the four walls now”, they tell me.

But I am yet to completely appreciate the use of the metaphor ‘prison’ for the lockdown.

Still not a prison

I was confined in three different prisons of the country — Tihar Central Jail in Delhi, Dasna District Jail in Ghaziabad and District Jail in Rohtak, from 1998 to 2012. Illegally arrested, at the age of 19, over fabricated charges of terrorism, I have spent 14 years of my life in prison.

And today again, I find myself confined to four walls without any sense of time, struggling to remember dates and days of weeks.

Much like in jail, I am avoiding handshakes, of course not out of fear of breaking the hierarchies of prison, but due to fear of spreading or contracting the virus. The pass system granting limited permissions to venture outside looks like the ‘parole’ system to me, although not all prisoners could afford it. My uncut hair and messy shave too are a reminder of my prison time.

But for all the metaphors of ‘prison’, this isn’t prison. Nothing kills human spirit like prison does.

Also read: This is how prisons across India plan to release and track 34,000 inmates

Luxuries outside prison

Today, although confined in our homes, we are with our families, parents, partners, and children to share our sorrows and smiles with. Prison does not allow you the luxury of family. Although prisoners are allowed to meet their families once or twice in a week, but in that small mulaqaat room, bursting with 100 different voices of prisoners and jail authorities, there is no privacy. In fact, there is a one-meter gap of wire mesh and grilles between you and your family. You cannot see your loved ones up close. You cannot touch them, hug them or cry with them. You are denied a comforting hug, the touch of loved ones for 14 years.

Today, we have the ‘luxury’ of opening windows, staring at the sky and stars. In prison, I had not seen stars for 14 years.

(I call all these a ‘luxury’ because many of our fellow citizens, the homeless and the migrants, are away from their homes and families. Most of them are struggling for even two meals a day).

We have the luxury of internet, calling friends, staying updated about the world. In prison, you are caged. Disconnected with the world, all you have is a continuous desperate ‘wait’ for court dates and returning to ‘normal’ life.

Also read: Jails give Covid-19 parole: Can overstretched govt track prisoners’ movement and behaviour?

Have you been in solitary confinement?

Our prison system actively recognises practices of ‘isolation’. The inhumane soul-crushing practice of solitary confinement is still part of the system. Tanhai as it is called, solitary confinement denies one of the most basic rights of a human being — the right to be able to interact with a fellow human being.

You are confined in an 8×6-feet cell in a deserted corner of the prison away from other prisoners. You are not allowed to meet other prisoners, and can only go out of the cell for one or two hours a day. Walk, eat, sleep, bathe, pee — all of this in that small 8×6 cell. Unsurprisingly, solitary confinement leads to mental health crisis, anxiety, depression and even suicidal tendencies for life.

So, no. This lockdown is nothing like prison. We are not in jails. We have been simply asked to follow norms of social distancing and stay home to control the spread of a deadly virus.

I do acknowledge that isolation, uncertainty, fear, silence, and helplessness are common feelings between both.

Also read: Political prisoners should be among first released in pandemic response: United Nations

Time for reform

Today, when we have gotten a glimpse of how isolation feels, perhaps we should push to make our prison systems more humane. Today, when we are struggling with limited space to move and walk, let’s think of those prisoners confined in 8×6 solitary confinement cells. When we are struggling to stay in touch with our loved ones, let’s think about those in the dingy mulaqaat rooms in prisons.

India’s prisons are still operating under the colonial structure, with little scope for human rehabilitation. The demand for reforming the system is urgent, and it cannot be delayed. I hope the lockdown teaches us that.

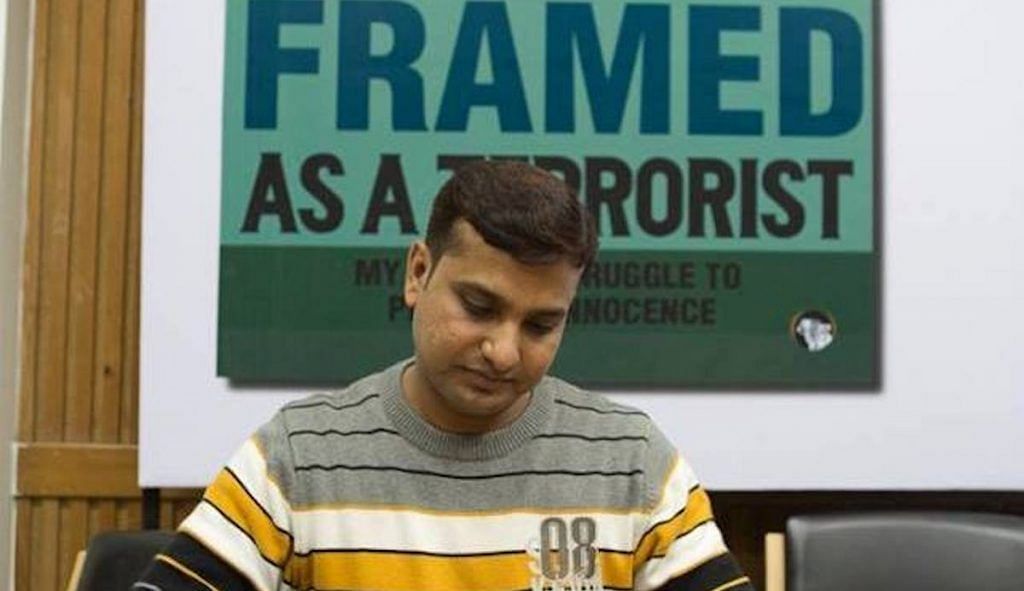

The author has written the book ‘Framed As A Terrorist: My 14 Year Struggle to Prove Innocence’ and is a human rights activist working with Aman Biradari. The article has been translated into English by Surbhi Karwa, NLU-Delhi alumni. Views are personal.