Kaala is filled with references to Babasaheb Ambedkar, Buddha, Bheem chawl, beef shop, Lenin and Bheemji.

Most storylines of an Indian film revolve around upper caste Hindus, with upper caste surnames, and their personal and family dramas. In such movies, the camera would rarely move away from their feudal homes.

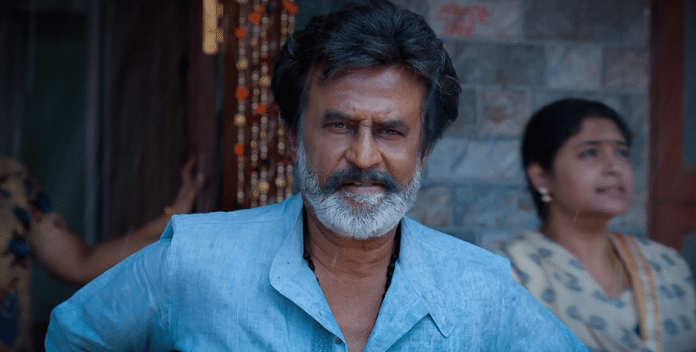

On the contrary, Pa. Ranjith’s movies – Attakathi (2012), Madras (2014), Kabali (2016), Kaala (2018) – firmly place the camera in a slum or a basti. The story is usually about the slum, instead of the individual.

In Kaala, the canvas gets bigger and overtly political.

Here, both the star Rajinikanth and the director Ranjith are breaking the myth about cleanliness, caste and colour, and arguing that land is a right. In the past, Dalit storylines were always about suffering, pain and tragedy. Ranjith deploys the commercial genre to celebrate the lives, anti-caste assertion and self-respect of Dalits.

Ram versus Raavan

Kaala, the protagonist’s name, means ‘Karikaalan’, a deity that’s considered a protector of the village. Kaala protects the slum, which is being encroached upon in the name of development by none other than the cleverly named ‘Manu’ builders.

The movie turns the mythical characters from Ramayana on their head. Here, the protagonist is Raavan (Kaala) and the antagonist is Ram (Hari dada). And Raavan cannot be killed because all the people in the slum are Raavans. On the other hand, Ram is killed by none other than the Raavans. Although the villain is always shown with the background engulfed in saffron colour and popular Hindu Gods, the movie is not against Hinduism. It is against ‘fascism’.

Kaala says in the film: “if you kill those who question you, then it’s fascism”. It reminded me of the murder of Gauri Lankesh.

Meet Lenin, Bheemji

There are too many references from the anti-caste movement to ignore.

Kaala’s wife calls him a ‘black panther’. The Dharavi slum is filled with colours of black, blue and red. The pictures of Babasaheb Ambedkar, Buddha, and references to a Bheem chawl, beef shop, masjid, and nikah fill the silver screen. Characters in Dharavi are named Lenin and Bheemji.

In contrast, when the antagonist appears on the screen, he is surrounded with saffron flags and billboards saying, “I am a patriot, I will clean this country”.

Ranjith also shows the diversity among the Dalit castes, including the Telugu-speaking arunthathiyars in Tamil Nadu.

Land as source of power

The underlying message in the film is that those who lost land became slaves and so land is important, as a right and as a source of power. This positioning of land at the centre of the Dalit struggle is something that many Dalit writers, activists and scholars agree on.

But my question is: If the land is given back to the slaves, will they become independent, equal and free? Land is important for becoming independent but caste cannot be erased by land alone.

In the movie, everyone says there is no room in the slum, and they have to share and forego notions of privacy. If there is not enough space or land, what is it that they are protecting and fighting for?

The grey areas

The biggest problem is that Kaala is shown as protecting the status quo. He does not display any vision for change or future.

Although women’s portrayal in Ranjith’s movies differ from the usual romantic leads, but Dalit women’s position in his movies still lags behind. In general, Dalit women have been critical about Dalit men’s gaze toward white skin or upper-caste women.

Ranjith, as a Dalit man, does something similar. Kaala’s wife, Selvi (Esawari Rao) is a dark-skinned woman. His ex-wife is Zareena (Huma Qureshi), who is fairer. She is a single mother with agency. Selvi is a person whose life revolves around Kaala, kitchen and cleaning.

These may not be obvious to all the viewers. But it depends on who is watching it with what gaze.

Some view the story as a face-off between Dravidians and Aryans, or the slum and the city, or land as a right versus colonising of land by corporate builders.

In the contemporary political situation, a movie with a superstar shown critiquing the government policies on silver screen deserves to be watched and appreciated.

B. Ravichandran is the founder of Dalit Camera. You can visit Dalit Camera’s twitter page @dalitcamera and YouTube channel for more details.

Print Barobar nahi bhava