In its last meeting involving current members, the RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee seems to have relied more on hope and less on the record of its predecessors. It is well known that any inflation rate in excess of 4 per cent makes our central bank uncomfortable. So, the decision to leave the repo rate and reverse repo rate unchanged, despite inflation breaching the 6 per cent mark, is surprising.

Also read: A central bank should be allowed to say ‘no’, says former RBI deputy governor Viral Acharya

Policy call on wrong assumptions

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) seems to think that the high inflation is attributable to supply chain glitches that can be ironed out in times to come. There seems to be some confidence from a normal monsoon progression and a satisfactory Kharif growing season. Both these assumptions are too convenient. The supply chain, which was brought to a grinding halt in March, has pretty much recovered, evident from the rise in e-way bill receipts that had plunged by almost 85 per cent in April. As per data on GST network portal, July saw a mere 7 per cent decline in the e-way bill receipts.

The food inflation too shows no signs of abating. As regards monsoon, it still can go awry and there can be disruptions and crop losses. Maharashtra and Karnataka have already issued flood warnings to several of their arable districts.

Also read: India has the biggest disconnect in the world between stock rally and economic gloom

Stagflation staring

The high inflation rate is a pointer to an inconvenient truth that the Narendra Modi government has been trying to ignore for a long time now — India is headed towards a stagflation phase of a magnitude we haven’t witnessed in several decades. As the popular duck test of abductive reasoning goes: if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it is probably a duck. By the same token, an inflation rate in excess of 6 per cent, a GDP that is set to contract by a minimum 8 per cent in the current fiscal year (some credible estimates put it even higher) and a dearth of demand, convey that Indian economy has all the signs of slipping into stagnation plus inflation territory.

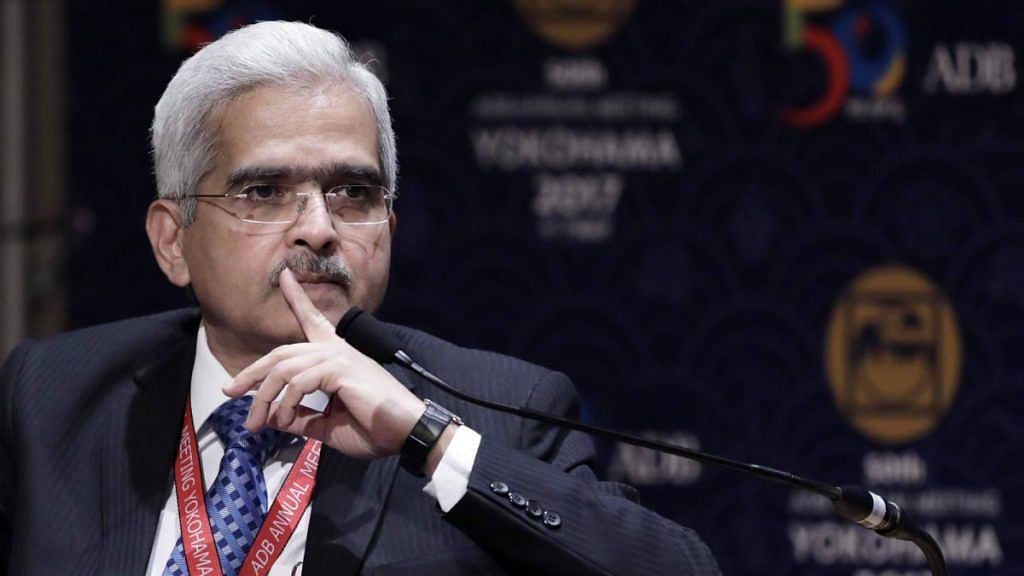

In Thursday’s briefing, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das admitted to a contraction in the economy, but was taciturn about the rate of decline. Silences apart, the apprehensions of stagnation are confirmed by other indicators as well. India’s June Manufacturing PMI stood at 47.2, an improvement when compared to May’s reading of 30.8. But it appears to have been a false dawn because the PMI for July has gone down to 46, indicating a weak recovery. A PMI reading of below 50 is indicative of contraction. Such economic indicators suggest that India is far from achieving a V-shaped recovery, and will have to settle for a U-shaped economic graph, characterised by a prolonged recessionary phase.

The world economic history shows that there is no greater test for policymakers than to deal with an economy going through a stagflation. Keynesian economics, the talisman used against most economic woes, too proved inadequate during the stagflation of early 1970s, paving way for the Friedman and Chicago School’s neo-classical economics. The 2008 global financial crisis brought Keynes back in vogue, best exemplified by the UPA government’s acclaimed MGNREGS.

Also read: Why loan restructuring is any day better than a moratorium — HDFC’s Deepak Parekh explains

No space to spend

So, do we go back to Keynes and start spending? Sadly, Modi government does not have sufficient money to propel a strong enough multiplier. Fiscal deficit for the period between April and June 2020 stood at Rs 6.62 trillion. This means the government, with over 7 months remaining in this financial year, has already ‘achieved’ 83 per cent of the fiscal deficit target it had set for itself. Therefore, there is hardly any fuel left in the tank. Public sector banks also don’t offer much hope either. The NPA problem is a monstrosity now. Bad loans now constitute close to 9 per cent of the gross advances, are expected to go up to 12.5 per cent by March 2021.

Also read: These are the 18 sectors that have been identified as ‘strategic’ for India by Modi govt

No MMT, please

So what are the options before the Modi government? There is a lot of talk going about what is known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a polarising radical new school of thought that calls for the government to not worry about fiscal deficit, spend money aggressively on job creation, print money if needed and then use taxes and borrowing to counter inflation.

In view of the Modi government’s record of taking dramatic policy actions, and timing them perfectly for an election, one can’t rule out the Centre dabbling with some form of MMT in October with an eye on Bihar assembly election. It may or may not prove useful for the BJP in winning the election, but the move will definitely not help the economy.

A lockdown that was introduced without any discussion with states, has crippled their taxation revenues. The Centre’s recent notice that GST reimbursement may not match the earlier promise, further imperils states’ prospects.

Also read: Every sector is trying to beat the pandemic and revive, says Finance Minister Sitharaman

What Modi should do

The Modi government needs to appreciate that an economic turnaround will require it to financially empower the workers who have come back to their impoverished villages. Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has aptly suggested direct cash transfers. It will also require the Centre to revive our moribund small and cottage scale manufacturing sector. The MSMEs may appear modest but contribute almost 30 per cent to India’s GDP. A revival of the MSME sector with investments in agriculture can meaningfully be implemented only by states because of their appreciation of regional realities.

One hopes that the Modi government understands this and comes out with a plan based on cash transfers to citizens and economic packages for states to revive their industry clusters. A resurgence of these clusters, will not only re-ignite economic activity, but also give fillip to exports, provide workers meaningful employment near their homes and improve state government taxation revenues. In short, this will produce a multiplier effect that Keynes would be proud of. The idiosyncrasy of MMT is best left alone.

Manpreet Badal is Finance & Planning Minister, Punjab. Views are personal.