Mass vaccination of the Indian population is critical to slow down the spread of Covid-19 infections and reduce case fatality rates. However, poor and faulty planning has led to an acute shortage of vaccines. Liberalisation of India’s vaccine “market” has allowed private capital to earn “superprofits” even as an economic crisis is building up and unemployment is rising.

To begin with, the Government of India (GoI) knew of the impending shortage of vaccines. India needed to vaccinate about 966 million adult persons, which would imply about 1,932 million doses of vaccines. If India must vaccinate everyone above the age of 18 in 12 months, the number of doses required would be at least 5.4 million per day. Even after considering the proposed capacity expansions of the Serum Institute of India and Bharat Biotech, India’s total production capacity was not to be more than 3.8 million doses a day. If we set aside about 15% of our capacity for external commitments, production capacity would shrink to 3.3 million doses a day in May 2021. Yet, while many countries approved a diverse basket of vaccines, India limited its official approvals to just two vaccines: Covishield and Covaxin. Why did India not put in place a liberal regime for approving, and importing, more vaccines?

Second, the vaccine business is risky, and early public investments serve to incentivise vaccine companies and reduce risk exposure. Many countries made large at-risk investments in vaccine companies for research and capacity expansion. India failed to do so. Given prior knowledge of the vaccine deficit, why did India not invest in capacity expansion, including in the public sector vaccine companies? Third, India also failed to place advance purchase orders for adequate quantities of vaccines. The first purchase order was placed only in January 2021.

Also read: Indians’ Covid experience is set to change trust level in political leaders, institutions

Once hit hard by the shortage of vaccines and rising public anger, the GoI reversed the irrational preference for just two vaccines. On 13 April 2021, it granted emergency-use approval to all “foreign” Covid-19 vaccines approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, and Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency Japan. For a government more eager to trumpet the achievements of atmanirbharta (self-reliance), this was a rather ignominious retreat. Nevertheless, vaccine supply is not expected to ease any time soon. New vaccines are not expected to arrive before June–July 2021.

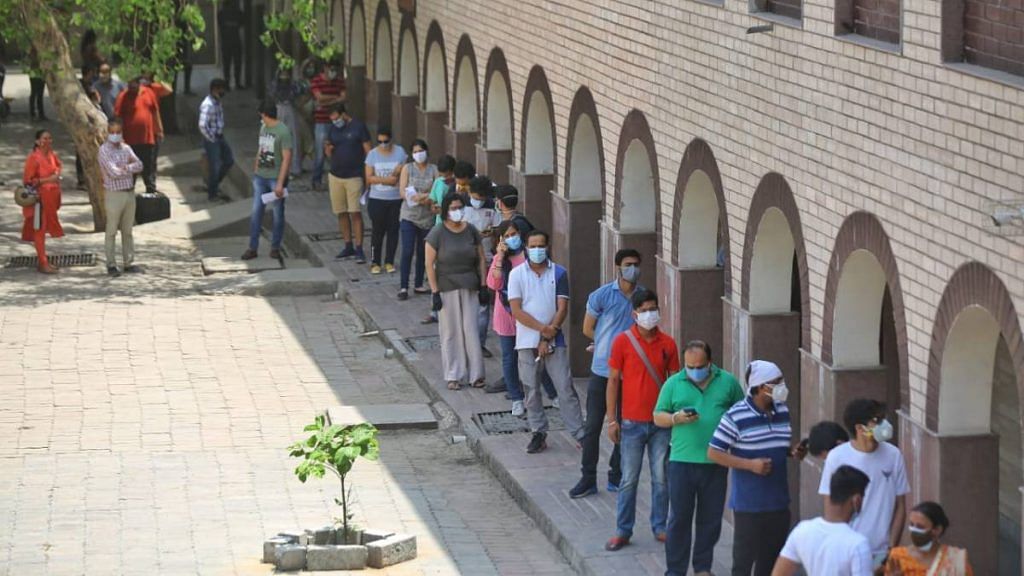

On 19 April 2021, India’s vaccine policy took another turn. Under the guise of opening up vaccination for everyone aged 18 years and above, vaccine sales were liberalised and vaccine prices were deregulated. Half of all vaccines produced were set aside for the Centre, but the rest were to be contracted and bought directly from vaccine producers by states and private hospitals. Vaccine producers, it was noted, would “transparently declare their self-set vaccination price.” Indeed, by self-admission, India’s monopolistic vaccine producers were making “normal profits” at the regulated prices. However, they desired “superprofits,” for which they lobbied hard to free prices from all regulations. Deregulation became a tool to quench the thirst of vaccine companies for superprofits.

Politically, the aim of the ruling dispensation was to evade responsibility for the vaccine shortage. If the states were asked to procure vaccines directly from the vaccine companies, the blame for vaccine shortages could be shifted on to their shoulders. The political image of the Prime Minister could be salvaged.

Ironically, many neoliberal commentators have conveniently overlooked the consequent fragmentation of India’s vaccine market. Different prices for different vaccines across the Centre, states and private hospitals would only encourage predatory practices in vaccine procurement. The outcome can only be a promotion of inefficiency and inequality and the absence of transparency. Efficiency and equity can be maximised only if vaccine procurement is public and centralised, if the vaccine market is regulated and if vaccines are shared across states based on socially desirable criteria.

Also read: States grapple with vaccine shortage, but Modi govt asks them to return ‘unutilised’ stock

Of course, there are multiple reasons why vaccines should be free and universal. First, vaccines should be global public goods. They impart not just private benefits, but also social benefits. As such, even mainstream economic theory concedes that vaccine markets are prone to market failures and suboptimalities. Most capitalist states, therefore, are providing vaccines free of cost to all citizens. Second, legal experts have tried to read the right to free vaccines as being implicit within the right to life and personal liberty enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution. Third, most vaccines, including Covaxin in India, are products of public-funded research. Public investments should not be allowed to be stealthily diverted into private profits, and taxpaying citizens deserve access to free vaccines. Fourth, charging for vaccines would make them unaffordable for a large section of the population, and exacerbate vaccine hesitancy. In sum, there is a clear case for public policy to supply vaccines free of cost to all citizens.

Unfortunately, the GoI has withdrawn from the social responsibilities of an enlightened welfare state. It has also opened the floodgates for a vulgar form of predatory capitalism to take over the stage amid the raging human tragedy. In fact, India’s vaccine policy has thoroughly exposed both the failures of an incompetent state and the vagaries of the “free” market.

R Ramakumar is Professor, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. Views are personal.

This article was first published in the Economic & Political Weekly (EPW) journal.