The extreme degree of centralisation in the UGC system that has grown 60-fold since 1950 has had negative effects on the quality of higher education in India.

The University Grants Commission’s (UGC) decision to grant greater autonomy to 62 institutes of higher education (including five central and 21 state universities) should ordinarily have been met with strong support from the academic community. The IIMs had already been granted this privilege through an Act of Parliament last year, and a move in this direction was long overdue.

The UGC’s role as a regulator of higher education has been deeply problematic, as it has sought to micro-manage a range of issues, ranging from faculty hiring to course offerings, which should ordinarily lie within the purview of a university.

The extreme degree of centralisation in a system that has grown 60-fold since 1950 (if measured by the increase in the number of colleges) or 75-fold (if measured by the increase in student enrolment) to emerge as the second largest higher education system in the world, has had pernicious effects on the quality of higher education in India.

The decision divided higher education institutions into two categories, with the first (Type 1 – those with an NAAC score of 3.5 and above) granted ‘full’ autonomy, and the second (Type 2 – those having a score of 3.26-3.5) given ‘partial’ autonomy, in that they would still need UGC permission for some activities, like signing contracts with foreign universities.

This autonomy relates to the freedom to start individualised courses, create new syllabi, launch new research programmes, hire foreign faculty, enrol foreign students, pay variable incentive packages to faculty, introduce online distance learning, and enter into academic collaboration with international universities, all of which are simply taken for granted in any good university around the world.

The UGC’s move has brought contentious reactions.

Protesters see it as a step towards the privatisation and commercialisation of education. The Delhi University Teachers Association (DUTA) sees it as “an erosion of rights to get higher education”. The Federation of Central Universities Teachers Associations has called the UGC decision “the misguided pursuit to make education market-determined and market-dependent”. These bodies, as well as other commentators, fear this move may lead the way to the privatisation of higher education and further inequality among institutions.

The privatisation bogey is somewhat unfounded. That horse bolted long ago. Today, a majority of the colleges (78 per cent) are privately managed (64 per cent are private-unaided and 14 per cent are private-aided) and account for 67 per cent of enrolment. Most of the privatisation occurred between 2000-01 and 2010-11, when the number of colleges increased by more than 2,000 annually, or about 5.5 per day (including weekends). Since then (2010-11 to 2016-17), the growth has been a more pedestrian 4.3 colleges a day! One could hardly expect higher standards from a regulator to ensure quality.

It must be emphasised that the vast majority of these private colleges are part of state universities, and all political parties have been party to this massive increase. If one presumes that there are ideological differences across political parties, then the common reason can only be the more banal one: There is money to be made.

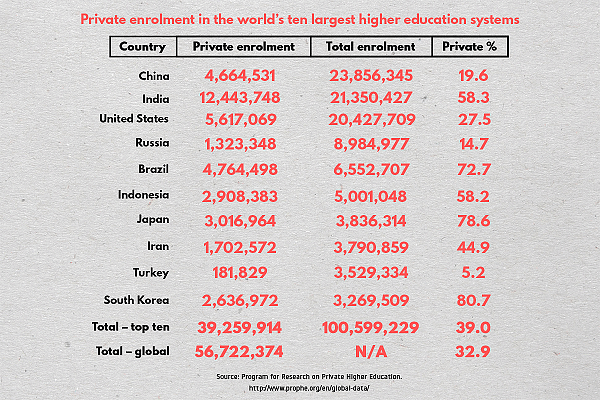

Indeed, India already has the largest number of students in higher education enrolled in private institutions. But there are several other major countries with a higher fraction of students in private institutions, such as Brazil (72.7 per cent), Japan (78.6 per cent) and South Korea (80.7 per cent).

Eighty-five per cent of Korean institutions of higher education are private, with approximately 78 per cent of university students and 96 per cent of professional school students enrolled in private institutions.

Government funding for Korean universities accounts for under 23 per cent of the total university revenue, significantly lower than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average of 78 per cent. Among the large countries, the United States, long seen as the bastion of elite private higher education, has actually a relatively low share of students in private institutions.

Private enrolment in the world’s 10 largest higher education systems

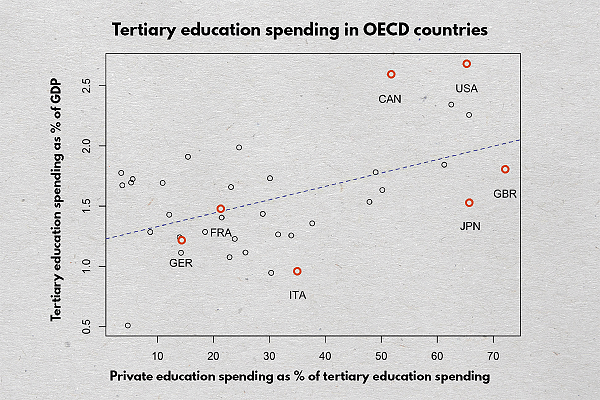

However, enrolment is only one indicator of the degree to which higher education is being supplied by privately-managed institutions. Another indicator is spending, which includes fees paid by students, and here the US story is rather different, as seen in the graph below.

Student debt in the US is now a staggering $1.5 trillion. In the Indian case too, the burgeoning supply of private higher education has been underpinned by massive loans to students from public sector banks – nearly Rs 68,000 crore outstanding in 2017, with NPAs touching nearly eight per cent.

What is different about the proposals from the UGC is that they are seen to be affecting the most privileged part of Indian higher education — central universities, although just five per cent of the universities are central universities (and their share of enrolment is even lower). In most countries, the most prestigious higher education institutions are public universities (the US is an exception). This is not surprising. Elite universities are research universities, and research is expensive as well as in public interest, both of which need public resources.

But the sheer expansion of higher education, together with constrained budgets, means that central universities need to become more creative in raising resources. The fact is that they are already the most pampered of higher education institutions in India, and when elite institutions press for more resources to pursue supposedly egalitarian goals, that argument only goes so far.

Fears that financial pressures to raise funds for new infrastructural and educational projects will lead to “commercialisation” are not unfounded. They can be a wake-up call to dysfunctional internal governance processes in these universities.

While student scholarships to ensure unbridled access, as well as revenue expenses such as salaries, need to be protected, there needs to be a shift in public funding for research from institutions to investigators, with built-in overheads for the host institution.

Concurrently, a gradual shift from grants to loan-based funding for capital projects through the higher education funding agency is necessary to impress on central universities that their funding is a privilege and not an entitlement. Central universities have miserably failed to raise resources from their alumni and they need to ask, if they are doing such a great job, why are their alumni so ungrateful? This is not about raising Rs 1 crore from a single alum, but a steady Rs 1,000 annually from 10,000 alumni. This takes hard work, but when money comes from the public exchequer, why do that hard work?

Indeed, there are other creative ways to raise money. The central universities sit on extraordinarily poorly utilised expensive land. JNU’s 1,000-acre-plus campus alone would be worth tens of thousands of crores at today’s land prices. If just one per cent of this was leased, the cash flows could support a steady annual revenue stream to support a large loan for a capital project, say better housing for students. And the leasing could be to create knowledge parks to support startups and strengthen university-industry linkages.

Unfortunately, proposals such as this would be dismissed by the lazy moniker of “neo-liberal”, which simply underscores the reality that while university communities are often progressive in their world-views, they are also deeply conservative about internal change.

Devesh Kapur is Madan Lal Sobti professor for the study of contemporary India, and the director of the Center for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania.