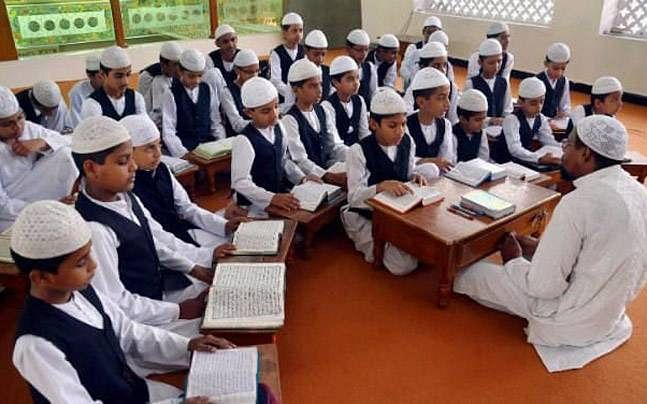

There is an urgent need to de-stigmatise madrasas as breeding grounds for terrorism, argues a new book that scrutinises the problems plaguing Islamic seminaries in the country.

This critical issue is addressed in the seminal text ‘Madrasas in the Age of Islamophobia’, where authors Ziya Us Salam and M. Aslam Parvaiz point out how madrasas, the cradle of Islamic learning in India, are going through challenging times and desperately need reforms and modernisation. The Islamophobic wave – where there is a tendency to brand students from madrasas as terrorists, for instance – is alienating Indian madrasas further.

Take for instance the case of Abdul Wahid Sheikh who was accused of being involved in Mumbai train blasts, but was acquitted nine years later. Or that of Salman Farsi earlier. Farsi, a hafiz, was said to have been involved in the Malegaon blasts. When he was acquitted some eight years later, he had nothing to fall back upon. A qualified doctor, he even took to rearing goats to meet his needs. These outcomes can be easily avoided. The media, instead of calling every accused a terrorist, perhaps could restrict itself to calling them only an accused, and refrain from splashing their pictures as if they have been convicted. However, that is only part of the solution. For a complete reality check, media personnel should visit an Islamic seminary of their choice to discover that no madrasa is a centre for keeping arms and ammunition or teaching students to use arms, suggests co-author Ziya Us Salam.

After thoroughly examining curriculums, the authors say reliance on classical books of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), their style, language, and examples are all caught up in a time warp. “They (curriculum) promote more enmity than debate and dialogue. They induce ennui rather than informed debate. Most commentaries taught to students are actually commentaries on commentaries! Certainly, not the ideal form for evoking interest,” the study says. Some notable exceptions are in southern India, particularly Kerala and even in the east in Bengal, where mathematics, English, and science are taught.

Ziya and Parvaiz, after carrying out an in-depth study of thousands of madrasas across the country, lament that aalim (scholar) of Islam coming from local madrasas is often synonymous with being ignorant of the world. “A community which made landmark contributions to science has become tied down to blind imitation and hidebound traditionalism,” they conclude in the book.

Also read: Everyone misinterprets Ghazwa-e-Hind, but a Jamiat scholar explains what it really means

Most madrasas teach Hanafi doctrine leaving out Islamic interpretation by other notable schools of thought such as Shafi’i, Maliki or Hanbali. “Almost all Sunni madrasas follow Dars-e-Nizami framed some 300 years ago. Very few modern-day additions have been made. Some Shia ones do the same too. But hardly any have space for Shia pattern of teaching with increasing emphasis on the so-called material subjects”, the authors remark, pointing how, in effect, most madrasas do not teach about Islam and teach only one interpretation of Islam to youngsters. “It is just assumed that a person will not need knowledge of these sects simply because they are in a small minority in India. Or that it is their interpretation of Islam is the only correct one, rest are all misguided.” This, according to Ziya and Parvaiz, is contrary to the Quranic directive that prohibits running down other faiths.

The scholars discovered that the curriculum of most madrasas in 2019 or 2020 could be easily replaced with the syllabus of a madrasa in 1920, or even 1870. “There is a timelessness to the whole affair which defies the message of the Quran. The Holy book asks mankind to think, explore and introspect. The madrasas ask the students to concentrate on memorising the Quran and ask no questions. Any attempt to ask questions is met with a rebuke; a student is supposed to toe the line.”

Education, as we understand, is an evolutionary process. However, in Indian madrasas, time stands still. Many seminaries still consult the 14th-century work of Ibn Kathir while looking for commentary of the Quran. For them, 20th-century works of Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi (also known as Ali Mian, Abul A’la Maududi), Israr Ahmed and Wahiduddin Khan merit no space. “In the timeless world of Indian madrasas the students are supposed to read and memorise the Quran with a finger on the book, a cap on the head, little inside; it is not unusual to find a hafiz-e-Quran who does not know the meaning of a single surah of the Quran,” the authors highlight.

Muslims, according to the authors, until the 12th century were at the forefront of scientific scholarship, discoveries, and inventions producing many great philosophers, doctors, mathematicians, and historians who relied on experimental methods, which is integral to modern science even today. In contrast, most madrasas in India do not provide their students any access to computers or the internet.

Also read: ‘Rich Muslims’ expense on Umrah, marriage can teach 3 lakh poor Muslim kids for 18 yrs’

Another major problem most Indian madrasas are facing relates to funds. Most Islamic seminaries are dependent upon charity money. In most residential schools, the students sleep on the floor in both the harshness of summers and winters. The authors found that in most classes, over 40 students sat crouched over the sacred book while two fans with twin blades providing them relief from temperatures exceeding 40 degrees Celsius. In winters, the students are asked to stir-clean a worn-out rug and spread it across the room. At night, the boys lie down, one after the other, on the same rug. There is no sense of private space in their residential area. A majority of madrasa students hail from poor families.

Most madrasas run without registration, even those with proper documentation and enviable history seem to be at the crossroads. According to Ziya and Parvaiz, only four per cent of the current Muslim population in India has studied in a madrasa at some point.

The government’s role and intervention is crucial, as the bulk of madrasa graduates cannot find jobs other than starting a new madrasa or taking up the role of a mosque imam or muezzin (one who calls the faithful to prayer five times a day). If teachers, books, internet, and computer are made available, madrasas could become modern and mainstream.

The author is a visiting fellow at ORF and working on a book on Islam and Indian Nationalism. Views are personal.

This article was first published on ORF.