India’s foreign and strategic policy is obsessively focused on Pakistan. But the latest incident along the Line of Actual Control is just one more proof why our focus should have always been on China first — our primary competitor and adversary. Successive governments, whether led by the Congress or the BJP, kept the Pakistan bogey at the centre of their South Asian policymaking, ignoring consistent reminders from India’s Socialist leaders to shift the attention towards the bigger threat, China.

None were taken seriously. And now we have a nuclear power in our neighbourhood that we mostly remain clueless about on how to deal with, even as new challenges — from economic to territorial — continue to arise, the latest being the Ladakh incursion.

So, who are these leaders who warned India about China’s enormous financial and military might — even as it was growing and hadn’t quite reached the state it has today — but were ignored at every turn?

Also read: India learnt the wrong lesson from 1962 China war. Modi govt must be more open

The farsighted politicians

A firebrand Socialist leader, Ram Manohar Lohia (1910-1967) was one of the few voices who would repeatedly caution Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru about China, especially when the euphoria around “Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai” (India and China are brothers) was developing after China’s annexation of Tibet in 1950. Lohia wanted a confederation of India and Pakistan — and had even signed a joint statement with Deen Dayal Upadhyaya in April 1964 — to counterbalance the might of China, whose aggression deeply bothered him. He had told Nehru that China’s annexation of Tibet would have serious implications for India because the ‘buffer’ was now gone.

His warnings were ignored. Despite annexation of Tibet, and China showing its expansionist policies regarding North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) and Ladakh, Nehru welcomed Chou En Lai, China’s first Premier, in 1956. En Lai visited India again in 1960. And then 1962 happened.

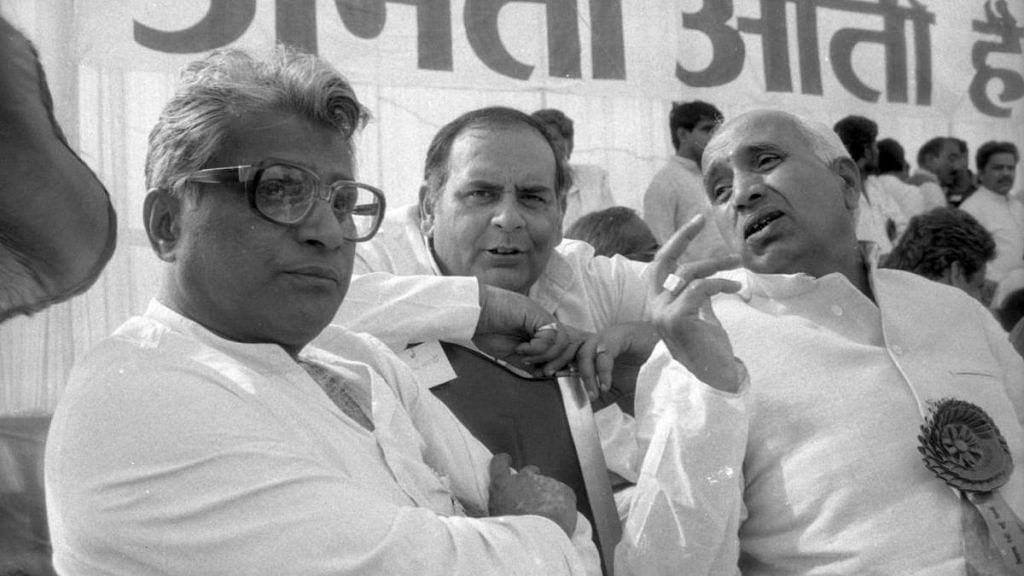

Between 1962 and 2020, at least two Socialist leaders — George Fernandes and Mulayam Singh Yadav, both of whom at some point wore the hat of defence minister — had said categorically that India should have a China-centric foreign policy.

Mulayam Singh Yadav, former Samajwadi Party president, would repeat his warnings about “dishonest” China in several speeches in the Lok Sabha, saying the neighbouring country would never “mend its ways” and always look to create troubles for India.

चीन की तरफ़ से ख़तरे और चुनौती को लेकर नेताजी ने समय-समय पर सरकारों को चेताया है लेकिन सरकार चीन की चेतावनी को लेकर उदासीन है… सरकार इसका जवाब कब देगी? pic.twitter.com/Dql1wCWYoH

— Akhilesh Yadav (@yadavakhilesh) June 16, 2020

Similarly, Samata Party founder George Fernandes, who was defence minister in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led NDA government, had described China as the “potential threat number one”, calling it India’s “error” to recognise Tibet as part of China. In an interview with journalist Karan Thapar soon after taking charge of the defence ministry in 1998, Fernandes said that “underplaying the situation across the Himalayas is not in national interest; in fact, it can create a lot of problems for us in the near future”. He also said in Indian politics, “there is reluctance to face the reality that China’s intentions need to be questioned”.

Both Mulayam Singh Yadav and George Fernandes wanted India to recalibrate its military and foreign policy accordingly.

Also read: Modi govt and military leaders have soldiers’ blood on hands. PM’s dilemma now same as Nehru

Pakistan or China?

Compared to Pakistan’s economic and military might, which even in the worst case can only inflict limited harm on India, China’s enormous financial and military strength means it will always remain a bigger challenge. Moreover, the contemporary and medieval history provide ample evidence about China’s expansionist policies, which are playing out in Ladakh once again.

And just as past governments ignored the Socialist leaders’ China-centric concerns, the BJP government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi appears further away from that position, mainly because its politics — and thus policies — is shaped by Hindu-Muslim binary, which Pakistan fulfils far more effectively than any other design or method possibly could.

But such an approach not only manifests in advancing the legacy of ignoring critical voices, it also takes our Asia policy away from the China threat and closer to scenarios where we are backstabbed by Beijing.

There is no denying that India’s inimical relation with Pakistan has had a huge role to play, shaped as this relation is by both the events of the past and present. During the later days of freedom struggle, the Congress and the Muslim League had turned bitter towards each other — a legacy that continued during Partition, entered the Kashmir conflict and shaped future India-Pakistan ties. And with the two countries always at war — overt, covert or ideological — it became a natural corollary that both Pakistan and India tried to align with China.

That is the genesis of the warmth and thaw in India-China relationship. But history bears testimony to how that thaw was short-lived. China showed its true colours, and India lost a large swath of land in the eastern theatre in 1962. The Galwan River Valley, which is part of the Eastern Ladakh, was successfully held on to at the time.

Also read: India can’t free-ride others to limit China. It needs to lead the containment strategy

Sleeping with the enemy

Even as border skirmishes and stand-offs with China grew, coupled with Beijing’s friendship with Islamabad, Indian prime ministers didn’t respond to internal voices sounding the alarm bell.

Vajpayee visited China in 1979 — the first high-level contact between the two countries after the 1962 war. This visit and the follow-up actions shaped India’s China policy for several decades.

Over the past six years, PM Modi has met Chinese President Xi Jinping as many as on 18 occasions. The bilateral trade between the two countries has soared to new heights, and Chinese investment in India increased from Rs 12,000 crore in 2014 to Rs 60,000 crore in 2017, which is currently estimated at close to Rs 2 lakh crore (including planned investment). Images of Modi-Xi camaraderie — whether over a cup of tea or coconut water or a swing — attempted to drive India’s China policy all through the PM’s tenure.

But all of that came to nought on the intervening night of 15-16 June 2020 at Galwan Valley, where 20 Indian soldiers, including a colonel, died a brutal death at the hands of Chinese soldiers. That’s the reality that neither the outdated ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai’ philosophy nor the ‘jhoola diplomacy’ can hide.

The one thing that can bring a change — and reduce the intensity of ‘shock’ India experiences every time China shows its real face — is linked to direct realisation of what Ram Manohar Lohia, Mulayam Singh Yadav and George Fernandes had said long ago. It’s time India made a course correction and turned its foreign policy gaze primarily towards China. Nothing less would do.

The author is the former managing editor of India Today Hindi magazine, and has authored books on media and sociology. Views are personal.