A friend recently sent me a data table from The Economist highlighting Pakistan’s inflation rate as the third highest in the world at 12.3 per cent. Unsurprisingly, people assume that the country’s recently released National Security Policy, which is being eulogised domestically in certain quarters as a great accomplishment, indicates a change in posture. Islamabad wants to correct its internal balance. It is believed that Pakistan is ready to look inwards and so has not gotten stuck with India’s Article 370 and has even talked about peace in the region.

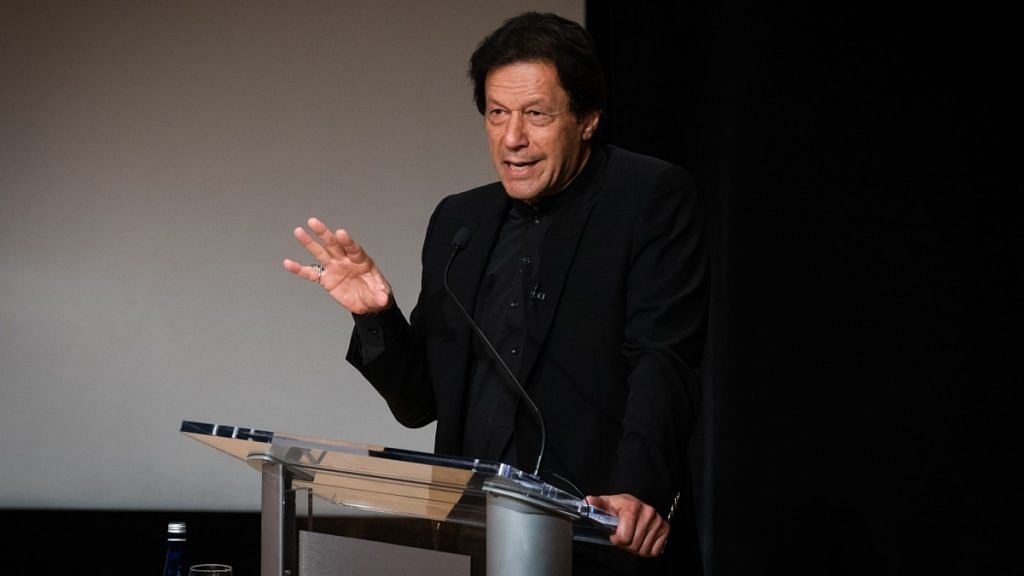

National Security Advisor (NSA) Moeed Yusuf, in any case, has been advertising the desired shift from geo-strategy to geo-economics. Such a leap is not likely because the National Security Policy (NSP) is cautious and not bold. Unlike his predecessors Nawaz Sharif or even Asif Ali Zardari, Prime Minister Imran Khan lacks clarity of heart regarding the necessity of peace in the region for which it is essential to reach out to the bigger neighbour.

It is not that Pakistan doesn’t feel the significance of focusing away from conflict and building trade ties with India, but that it is overpowered by its tactical-cum-strategic need to improve its conditions while not looking weak. It is too burdened by its military to start looking inwards and mending its domestic fences. The mess is far greater than what the American-trained NSA could clean without mending the fence where it ought to be. The civil-military imbalance, which is far too central to managing the shift from geo-strategy to geo-economics, has just not been addressed.

Also read: Read my lips, I’m hurting, says Pakistan’s National Security Policy. What it means for India

NSP has its roots in Nawaz Sharif govt

Notwithstanding the impression that may be created about this being a new effort, the history of the NSP dates back to early 2013. I remember the grapevine in Islamabad was abuzz with stories of the army chief’s interest in building trade relations with New Delhi. Then-Army Chief General Ashfaq Kayani had even mentioned during his address at the Pakistan Military Academy, Kakul that the country’s real threat was internal and not India.

Kayani, with a reputation of being a thinking general, may have wanted to focus on the bigger problem of terrorism inside the country, and to some extent, the economy. His extension, however, weakened him, especially against institutional hardliners. I remember from my conversations with various generals, especially former DG ISPR, Major General Athar Abbas that the army was open to the concept of trade with India but not to the idea of allowing Nawaz Sharif to chart his own course.

But this was not the only change that Kayani aimed for. In his perception, the starting point of peace then and even now is rearranging governance to include the military institutionally and on a permanent basis. In 2013, then-newly-elected Nawaz Sharif government agreed to shift away from the system of the Defence Committee of the Cabinet (DCC) and move rather hurriedly to the Cabinet Committee for National Security (CCNS) in which the four senior generals would get invited without becoming its members.

Soon after, the prime minister changed the structure and the nomenclature. It was called the National Security Committee in the same pattern as the National Security Council. The four senior generals were equal members, and the NSC was given a decision-making role. Nawaz Sharif was probably unwilling, which is why he only convened the NSC meetings nine times and was accused of leaking information to the press, hence the famous Dawn leaks.

Interestingly, his first National Security Advisor, Sartaj Aziz, agreed to the idea of the NSC and supported this system of governance. In his book Between Dreams and Realities, Aziz talks about the lack of capacity of parliament to deal with military matters such as arms procurement, which is why the new system aimed at harnessing parliamentary powers.

A system to favour armed forces — ‘why not?’

There are quite a few of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) senior leaders who are happy to support a system that tips the balance of governance in favour of the armed forces or nurtures a permanent role for the generals. This also means that even with a change in government that could happen after the next elections, the NSP and its institutional paraphernalia will stay. Though highly ambitious, the NSA plans to institute a system whereby the National Security Policy turns into the main machinery of the government. It can then not only refine and revise the vision statement annually or whenever the need arises, but also monitor its implementation.

Reading through the various articles that have been written thus far commanding the effort, it is only former Foreign Secretary Aizaz Ahmed Chaudhry who has pointed out the potential problem of inter-institutional rivalry.

Other departments that have been there long enough will have issues. But then, Moeed Yusuf’s best bet is investing in a military-bureaucratic structure that does not challenge the senior commanders but offers to play second fiddle.

NSP follows ‘have your cake and eat it too’ pattern

An imbalanced civil-military governance formula is a bane for any possible change in Pakistan, leave alone taking a herculean step from military security to economic and human security. It was just a few days before PM Imran Khan launched the NSP and highlighted his government’s transformative spree, when Interior Minister Sheikh Rasheed Ahmad announced a deal with China to purchase 25 J-10 fighter aircraft to improve the conventional arms balance, which, in the minister’s view, was disturbed by the Indian Rafale.

The military establishment may be in a bind to improve the economy and increase the size of the pie to get a better share for itself. However, this is a Catch-22 situation, as economic development and growth require diversion of resources from the military to civil sectors and for the armed forces to allow the political class to take control of governance. In this respect, the NSP has a ‘have your cake and eat it too’ flavour that it has tried to present on paper — a perfect balance between military security and the much-needed human and economic security without doing any serious calculation.

Moving towards complete State control

In the last 10 years, the Pakistani military has acquired several major weapon systems for the Navy to focus on the growing maritime security needs. The Air Force has also cautiously, if not greedily, satisfied its palate. Not to mention the consistent expansion of the military-business-industrial sector, where the armed forces and their welfare agencies have gradually entered every field. This not only leaves little for the private sector but also limits options for the civilian sector to explore and add to the economy.

The military-dominated authoritarian structure of the State is likely to solidify with the next elections. A possible change in the political party formula in parliament is not necessarily going to change the political balance. The establishment has weathered that part of the domestic storm where it feared a spate of resentment from the general public. The resentment against poor economic conditions and the Khan government has not multiplied to a meaningful resistance against military authoritarianism.

This also means well for the longevity of the National Security Policy, which will continue to thrive and excite security and policy geeks in the region about coming up with equally smart formulas. The NSP is good to showcase, but not likely to be effective for real change.

Ayesha Siddiqa is Senior Fellow at the Department of War Studies at King’s College, London. She is the author of Military Inc. She tweets @iamthedrifter. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)