Jamal Khashoggi’s death should matter. It should not be ignored or treated as secondary.

I’m not proud of it. But I am one of those people who are more viscerally upset by the allegations that journalist Jamal Khashoggi died a brutal death at the hands of Saudi secret police than by the deaths of thousands of people under Saudi bombardment in Yemen. The reason isn’t that Khashoggi was a journalist or that he was a legal U.S. resident or that he may have been dismembered, possibly while still alive. It’s much simpler and much less principled than that: It’s because I knew him.

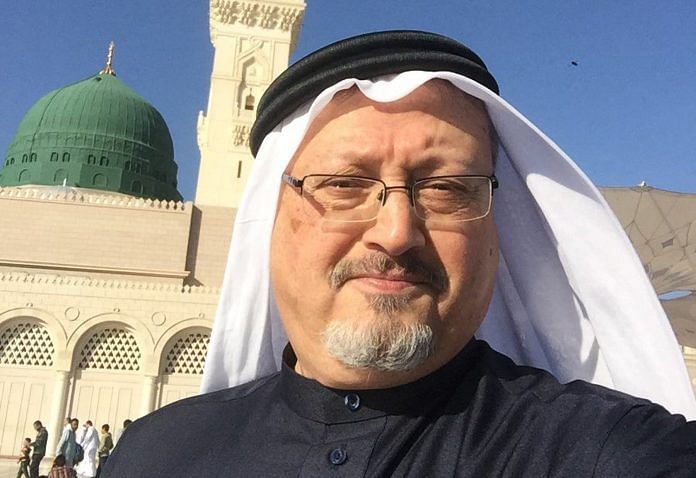

Many thousands of people knew Khashoggi — and many of them, at least in U.S. circles, were foreign policy types or journalists. For roughly 20 years, he was one of a handful of English-speaking Saudis who took the time to meet with researchers, scholars, writers, government and nongovernmental officials to explain the opaque system of government that is the kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Who Khashoggi knew is having a direct impact on the debate about how the U.S. should respond to his disappearance. There is a very large overlap between the people whose job it is to debate this policy issue and the people whom Khashoggi had met over the years.

The great majority of the Americans who met Khashoggi were not his close friends, but rather professional acquaintances, as I was. What’s more, almost all of them are cynical (or, if you prefer, sophisticated) enough to understand that the death of one journalist wouldn’t ordinarily be enough to upset the national security and economic interests that have long made the U.S. and Saudi Arabia close allies.

Yet for the moment, at least, the collective outrage over his disappearance and likely gruesome death, as described by Turkish authorities, is threatening the U.S. policy of building extremely close ties with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, or MBS, as people in the know like to refer to him.

Is this right? Should personal and professional knowledge of the missing man affect our collective discussion about relations with an important ally?

There are two strong arguments against allowing personal feelings to shape policy in a situation like this. Intriguingly, they come from almost diametrically opposed worldviews.

The first argument is a moral one, grounded in the essential truth that every human life is equally valuable. This instinct drives the perfectly legitimate criticism that those who are now criticizing Saudi Arabia over Khashoggi’s death have not spoken out anywhere near as forcefully about the Saudi war in Yemen or other commonplace Saudi human rights violations, including the imprisonment, torture and even killing of dissidents.

On this view, the fact that you know someone is a temptation to the moral error of acting as though his life is more important than the lives of others whom you don’t know.

The other, radically different argument against letting emotions into the policy debate belongs to the hard-core foreign policy realists. To them, foreign policy must be based on long-term, consistent national interests. From this perspective, it’s a categorical mistake to think that the death of any one person could realign how the U.S. should treat Saudi Arabia. Realists don’t have to be totally amoral — they can believe, for example, that in the long run realism saves lives, averts war and leaves everyone better off. But realists are committed to the idea that the life of a friend or acquaintance does not provide a reason to re-evaluate geopolitical strategy.

But there’s something very powerful on the other side, too: the moral intuition that we ought to care and speak out about a heinous wrong done to someone whom we know.

In this sense, meeting someone face-to-face has inherent moral significance. Indeed, some philosophers, like the French Jewish thinker Emmanuel Lévinas, have tried to make the face-to-face encounter into the most basic building block of our moral obligation to other humans.

You don’t have to go that far to believe that we would be moral monsters if we didn’t feel and react strongly to the murder of someone we know. Our empathy for strangers or people in faraway places has to be learned from the more immediate empathy that we experience for those close to us. An acquaintance isn’t as close as a family member or a personal friend; yet an acquaintance is still a meaningful form of human relationship.

The importance of genuine moral concern and genuine moral outrage is why it is acceptable, and even desirable, for people who knew Khashoggi to speak out and demand that his awful death, if confirmed, be given weight, meaning and consequence. It’s natural that different people will want different policy initiatives to make his death worthwhile. I’m not, in this column, arguing for one or another, although I have my own ideas.

What those people have in common is the morally legitimate yearning for a reckoning. Jamal Khashoggi’s death should matter. It should not be ignored or treated as secondary — even if part of the reason for that is that he knew a lot of people whose job it is to try to make the world take notice of things— Bloomberg.

The way he was eliminated ,hate to describe his death , is simply satanic behaviour. Even animals kill their prey before eating it. DT is irrelevent in this sad event.