Near the ruins of the royal palace at Polonnaruwa—Sri Lanka’s most important medieval city—is a rather unassuming open-aired hall. On one of its stone slabs is an inscription of a queen called Sundara-Mahadevi, or Sundari, from the distant land of Kalinga (present-day Odisha). Her unassuming stone inscription reveals a wild history of dynastic intermarriage and international political wrangles, behind which loomed the growing power of Sri Lanka’s Buddhist Sangha.

Marriage and the mainland

To understand how an Odia queen ended up in Lanka in the first place, we need to note that such exchanges are not exactly surprising. As seen in an earlier edition of Thinking Medieval, the island was deeply integrated into South Asian movements of goods, people, ideas, and capital. One of the most visible aspects of this was the sheer degree of intermarriage between the island and mainland dynasties.

Up to the 7th century CE, notes historian Thomas Trautmann in Consanguineous Marriage in Pali Literature (1973, cited in Gornall 2020, page 20), Sri Lankan royalty married almost exclusively among themselves. The island’s governors, generals, and officials all came from within the same family tree (or family bush). But as exchanges with the mainland grew in the 8th and 9th centuries, political and matrimonial alliances were made with dynasties from South India, especially the Pallavas of Kanchipuram. In the 11th century, the Cholas emerged as an existential threat to Lankan sovereignty, extinguishing the island’s line of kings at Anuradhapura. Lanka’s political structure shattered, and new chiefs rose to take control of its different regions. It is in this context that queens from Odisha begin to rise to prominence, appearing in monastic chronicles such as the Culavamsa as well as in the inscriptional record.

Also read: Dancing Shiva in Samarkand: Central Asian traders spread Hinduism, Buddhism along Silk Road

Why Sri Lankan rulers sought matches from Kalinga

It’s unclear why princesses from distant Odisha were considered such desirable matches for Lankan royals. Since much of India’s east coast was under Chola hegemony—with the exception of Odisha and Bengal—it’s possible that it was considered one of the few viable geopolitical rivals to Chola power. Vijayabahu I (r. 1055–1100), the warlord-turned-king who first drove the Cholas from the island, married Trilokasundari, a princess from Kalinga. Their son was married to his Odia cousin, the aforementioned Queen Sundari.

It is also possible that Odisha and Lanka had deeper, older ties. In Odisha: Cradle of Vajrayana Buddhism (2013), professor Umakant Mishra argues that the region had some of India’s most important centres for the development of tantric or esoteric Buddhism. And though Sri Lanka is best known for “orthodox” Theravada Buddhism today, it was also a major tantric Buddhist centre at one point. The famous Indian tantric master Vajrabodhi—a member of the Pallava dynasty—stopped in Lanka in a monastery known as the Abhayagiri Vihara to learn and collect texts on his way to China in the 8th century. Esoteric Buddhism thrived on the exchange of texts, and it’s very likely that the monks and libraries of the Abhayagiri Vihara were linked to monastic centres in Odisha, such as Ratnagiri. All this goes to show that geopolitics was just one aspect of the multidimensional connections that bound together the medieval world; equally important were religions, rituals, texts, and families.

Also read: A medieval Malayan king beat Cholas at their game. Almost created a superpower

Dynasties are temporary, but the Sangha is forever

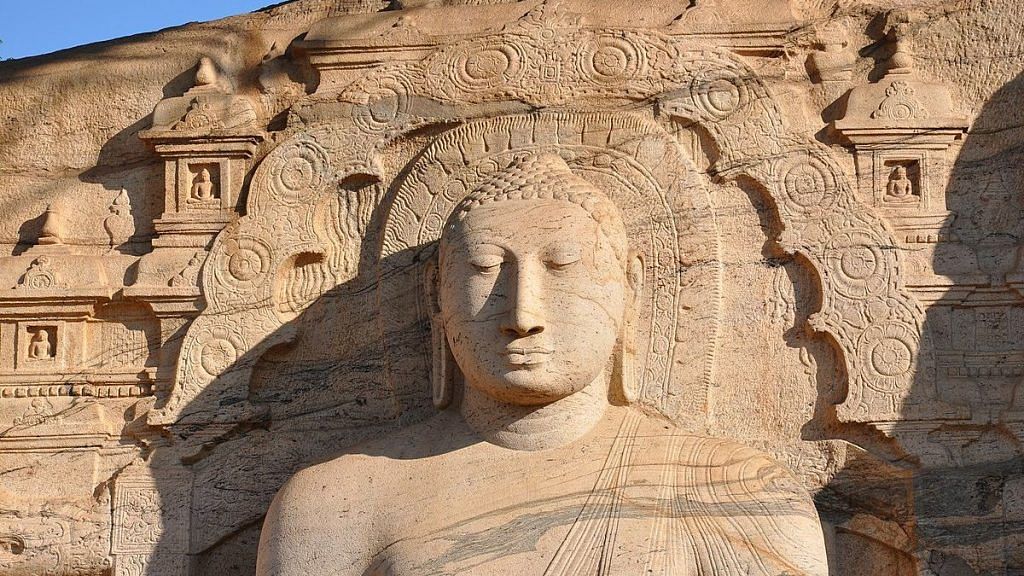

The Abhayagiri Vihara was once the island’s dominant school, but by the time of Queen Sundari in the 12th century, it had been subsumed by the orthodox Maha Vihara. The Maha Vihara—in the manner of dominant religious institutions everywhere in the world—took over not only the patrons of the Abhayagiri Vihara but also some of its ritual practices, such as royal consecration. All this, of course, while claiming to be the direct descendant of the Buddha’s teachings, which have little to say on such royal-friendly rituals.

As much as it had adapted itself to royalty, the Maha Vihara would brook no royal interference in its affairs or its property. Writes Alastair Gornall (2020, page 28), an Odia queen, possibly Vijayabahu I’s wife Trilokasundari, “made the error of seizing property belonging to the monastic community and, in a theatrical show of deference, the king ‘had her led by the neck and evicted from the city’ [of Polonnaruwa].” Queen Sundari, who was both Vijayabahu’s niece and daughter-in-law, would not make the same error. By the time she and her husband came to power in the 12th century, rebellions and conspiracies were already afoot. Her husband had infuriated the Sangha by appropriating several properties, using them to pay for his army. She had to find a way to appease them.

This brings us to the inscribed slab mentioned earlier, possibly the clearest indicator of Sundari’s sharp political instincts. The inscription borrows the basic format used on the mainland, which has a Sanskrit eulogy (prashasti) to a political overlord preceding a eulogy of their vassal. And so Sundari’s inscription begins, praising her overlord, from Epigraphia Zeylanica Volume 4 (1934, page 72):

“Hail! Prosperity! May that noble chief of monks, known by the name of Ananda, be victorious—[he] who has obtained psychic power, who is like unto a banner raised aloft in the land of Lanka…”

Ananda, the monk, apparently, is the overlord to whom Sundari subordinated herself! The inscription continued to praise her marital dynasty, once again using terms and images familiar from Indian royal eulogies, but instead written in Pali, the language of Lanka’s Buddhist Sangha. This was an indication of the growing might of the Sangha. In the midst of dynastic and political chaos, Buddhist institutions were silently consolidating their territory and wealth, asserting themselves as the island’s primary power. What Sundari seems to have done in response is taken political and literary ideas that worked well in mainland South Asia, adopting them to her own political context. Sanskrit was replaced by Pali, and the ruling dynasty was supplanted by the Sangha.

But did this inscriptional sleight of hand work? All indications say yes, but not perfectly. Sundari’s son, Gajabahu II, was almost killed by his usurping relation, Parakramabahu I. But the Sangha stepped in and brokered a peace treaty, saving his life in return for appointing Parakramabahu I as his successor. Parakramabahu’s descendants would go on to become Lanka’s primary ruling house for many generations after, fighting off (among others) the invasion of the Malayan king Chandrabhanu in the 13th century. Before these great clashes was a queen who was only trying to save her child, exemplifying the human lives at the centre of the complex exchanges of the medieval world.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)