Censorship in response to moral panic and outrage was the norm, but now in India, we’re even cutting out the middlemen.

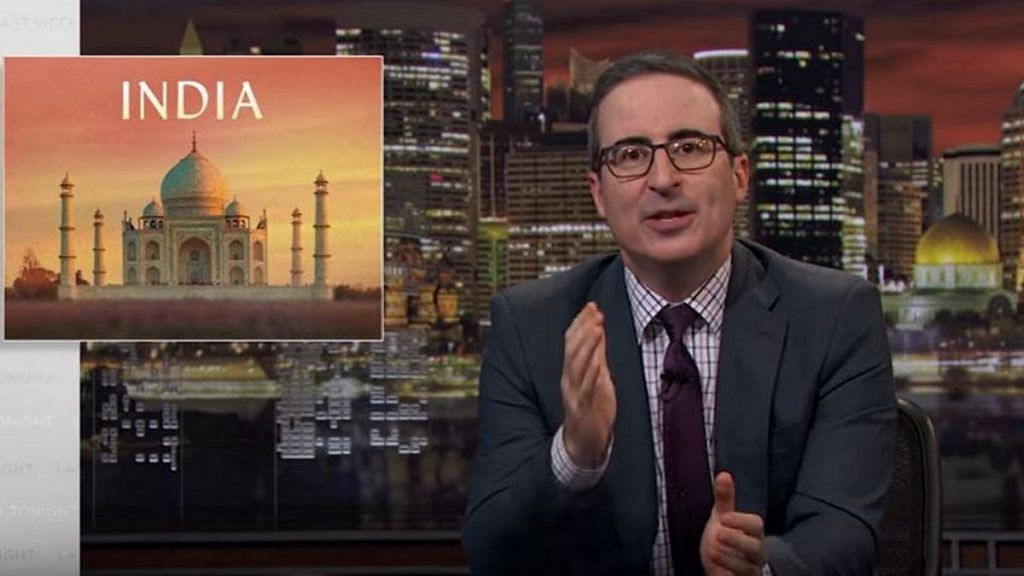

When riots were taking place in northeast Delhi and US President Donald Trump was set to land in India, HBO’s popular Sunday night show Last Week Tonight hosted by John Oliver aired an episode on Prime Minister Narendra Modi. This episode, however, did not appear on Hotstar’s listings for the show, which are normally updated Tuesday mornings in India (it has still not been added at the time of writing this). International publications like Time magazine and The Economist have been the subject of outrage for carrying stories critical of PM Modi in the past. Netflix, too, has faced criticism for producing and housing shows like Leila and Sacred Games. Perhaps, the desire to avoid facing similar public anger prompted Disney-owned Star India to take this step.

It is important to look at the implications of this intervention.

Also read: Hotstar blocks John Oliver show critical of Narendra Modi

All the world’s an outrage

A moral panic is a situation where the public fear and level of intervention (typically by the state) are disproportionate to the objective threat posed by a person/group/event.

In India, one of the most infamous cases of a technology company bowing to moral panic occurred in January 2017. The Narendra Modi government threatened Amazon with the revocation of visas when it became aware that the online retailer’s Canadian website listed doormats that bore the likeness of the Indian flag on them. It was fitting that this threat was issued on Twitter by then External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj, since the social networking platform was also the place where the anger built-up. It should come as no surprise that Amazon acquiesced, even though it was bound by no law to do so. While such depictions of national symbols are punishable under Indian law, it is debatable whether it should apply to the Canadian website of an American company, not intended for India-based users.

This wasn’t the first instance of sensitivities being enforced extra-territorially on internet companies and certainly won’t be the last. And this is very much a global phenomenon. While the decision by the Chinese state channel CCTV and several other companies to effectively boycott the NBA team Houston Rockets and the censorship of content supporting Hong Kong protests by Blizzard Entertainment garnered worldwide attention, these were only the latest in a long list of companies that have had to apologise to China and ‘correct’ themselves for issues like listing/depicting Taiwan as a separate country or quoting Dalai Lama on social media websites that were not even accessible in the country.

In Saudi Arabia, Netflix had to remove an episode of Hasan Minhaj’s Patriot Act that was heavily critical of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. In the United States as well, content delivery network Cloudflare has twice stopped offering services to websites (Daily Stormer in 2017 and 8Chan in 2019) when faced with heavy criticism because of the nature of content on them. In both cases, CEO Matthew Prince expressed his dismay at the fact that a service provider had the ability to make this decision.

Also read: Kashmir, parenting, sex – Podcasts are finally giving Indians what they want to hear

Of Streisand and censorship

The key difference in the current scenario is that Hotstar appears to have made a proactive intervention. There was no mass outrage or moral panic that it was forced to respond to. By choosing not the make this John Oliver episode available on its platform, it effectively cut out the middlemen and skipped to the censorship step. A move that was ultimately self-defeating since the main segment of the episode is available in India through YouTube anyway and has already garnered more than 60 lakh views while the app was subjected to one-star ratings on Google’s Play Store.

The attempt has only drawn more attention to both the episode and the company itself. This is commonly known as the Streisand Effect. Although a more cynical assessment could be that this step has earned Star India some ‘brownie points’ from the Modi government.

Earlier this month, The Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI) announced a new ‘Self-Regulation for Online Curated Content Providers’ with four signatories (Hotstar, Jio, SonyLiv and Voot). Notably, an earlier version of the code released in February 2019 had additional signatories that chose to opt out of this version. It was also reported that some of the underlying causes for discontent were lack of transparency, due process and limited scope of consultations in the leadup to the new code.

Some of broad changes in the new code include widening the criteria for restricted content from disrespecting national symbols to the sovereignty and integrity of India. It also empowered the body responsible for grievance redressal to impose financial penalties. In addition, signatories of the code and the grievance redressal body are obliged to receive any complaints forwarded/filed by the government.

Also read: The Virtual Private Network of your internet may not be fully private

A letter by Internet Freedom Foundation to Justice A.P. Shah, cited as concerns, the code’s consideration of the reduction of liability over creativity and the risk of industry capture by large media houses. The pre-emptive action taken in case of Last Week Tonight’s Modi episode perfectly encapsulates the risks of such a self-regulatory regime. It signals both intent and potentially the establishment of processes to readily restrict content deemed inimical to corporate interests. Such self-censorship, once operationalised, is a slippery slope and can result in much more censorship down the road.

The general trend of responding to outrage by falling in line was problematic in itself. But in India’s current context, the eagerness to self-censor is significantly more harmful especially when you consider that other forms of mass media are already beholden to a paternalistic state with severely weakened institutions.

The author is a research analyst at The Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy. Views are personal.