Growing up in post-colonial Bombay – now Mumbai – as a Midnight’s Child in the 1950s, for me Robert Clive, the man who conquered India for the British, was still a historical hero to be revered at my Anglican Cathedral School, alongside more recent national figures like Akbar, Shivaji and Gandhi. Today, Clive has been knocked off his pedestal by the anti-colonial Left, variously labelled a greedy plunderer, a ruthless trickster and even a “social psychopath”. Which version are we to believe, since historical writing about him can be so conflicting?

The most famous example was the long essay about him by the great historian and imperial statesman Thomas Macaulay. “Clive, like most men who are born with strong passions and tried by strong temptations, committed great faults”, wrote Macaulay a century later in 1851. “But every person who takes a fair and enlightened view of his whole career must admit that our island, so fertile in heroes and statesmen, has scarcely ever produced a man more truly great either in arms or in council.”

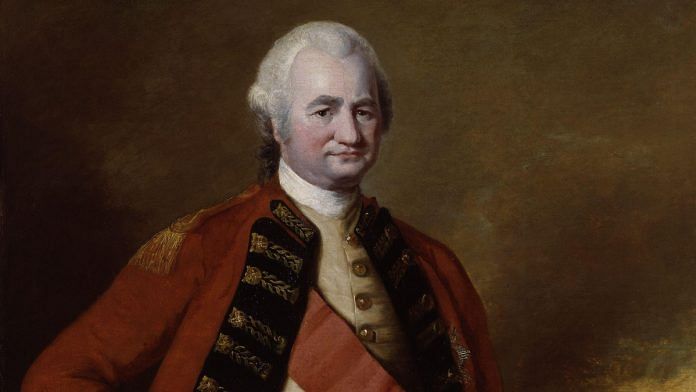

Robert Clive’s reputation has waxed and waned through the ages, depending on who was writing his history, colonialists or nationalists, Britons or Indians. Why should we care now? Possibly because Clive, more than any other British imperialist, epitomises both the enormous achievements and the frailties of Western empire-builders.

Also read: How the nexus of business and state gave birth to the East India Company

Orphan to East India Company

We know that he began life as an orphan, born into a minor gentry family, brought up by a devoted aunt and uncle. Perhaps because they indulged him too much, he was known for his temper and fights as a child and, according to Macaulay, even held shopkeepers in his village to ransom by threatening to break their windows. He grew up into what the great diarist Horace Walpole described as a “remarkably ill-looking man”.

His early career at the East India Company as a young writer or clerk in Madras (now Chennai) was not promising. First, there was the probably apocryphal tale of his aborted suicide attempt. “After satisfying himself that the pistol was really well-loaded,” Macaulay observed, “he [Clive] burst forth into an exclamation that surely he was reserved for something great.” Clive was accused early on of being very rebellious towards his supervisors, including even a fight with the local chaplain. He was hauled up for this before the Governor of Madras and his Council, who nevertheless exonerated him and reported to the Company’s directors that he was “generally esteemed a very quiet person and no ways guilty of disturbances”.

We are told that Clive showed no colour prejudice towards the “natives” and adopted local customs such as smoking a hookah and chewing supari. Like other young writers, he went happily ‘whoring’ at local brothels with native women, despite several doses of the clap. What was unusual, given his lack of any military training, was his involvement as a young officer in the Company’s small but highly effective private army of native sepoys.

Also read: ‘Macaulay’s Children’: Do we really need an English Language Day in a post-colonial world?

A young captain

As a budding young captain, Robert Clive found himself caught up in a war between two Indian potentates, the decadent, spendthrift Muhammad Ali, Nawab of the Carnatic, and his formidable rival Chanda Sahib, each backed by the rival British and French East India Companies. Clive, we are told, was popular with his sepoys because he never shirked sharing their hardships and dangers. He discovered early on how huge Indian armies could be frightened off by a small but disciplined European-led force. His breakthrough came, aged only 26, with his dramatic siege and capture of Chanda Sahib’s capital of Arcot.

While Chanda Sahib was busy besieging Muhammad Ali at Trichinopoly, Clive managed to drive out his huge garrison at Arcot and to hold on to it against the French forces who came to Chanda Sahib’s aid against the British. Clive is reported to have treated the inhabitants of the city very kindly. During the siege of Arcot by the French, “the sepoys”, we are told, “came to him, not to complain of their scanty fare, but to propose that all the grain should be given to the Europeans, who required more nourishment than the natives of Asia.” Buoyed up by such loyalty, Clive rejected large bribes from Chanda Sahib’s son, and his heroism turned the tide of the Carnatic War, ending in the death of Chanda Sahib and a sound defeat for his French backers.

Clive’s bipolar disorder and India dispatch

It was about this time that Clive had the first of the several psychosomatic illnesses that would dog him throughout his career. A modern diagnosis suggests a bipolar disorder, accompanied by severe stomach cramps, a condition for which there would have been little sympathy or remedy back in the 18th century. Poor health drove Clive back to England for a three-year interlude. Although aged only 27, he found himself already a military hero and the toast of London. He and his wife Margaret, with their growing brood of children and their two Indian Christian servants, set up house in London’s Ormond Street.

Clive’s ambitions were, by then, already centred on Westminster as much as India. Having tried and failed to get elected to the House of Commons, he returned to India in 1755 with the rank of colonel and deputy-governor of Madras, where the East India Company was still locked in a struggle for mastery with its French rival. But it was to Bengal that he soon found himself dispatched to retrieve the Company’s fortunes from the fall of its Calcutta factory to the ambitious young Nawab of the province, who was also intriguing with the French.

Black Hole of Calcutta and revenge

The tragic saga of Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah’s quarrel with the Company, his seizure of Calcutta and the Black Hole disaster, in which a disputed number of British civilians, women and children suffocated to death, is well-traversed, as is Clive’s role as the Company’s avenging angel. Less familiar is the extent to which Clive was egged on by the Nawab’s own courtiers, and especially his Hindu bankers and administrators. Prominent among these was the Jagat Seth family, bankers to the Nawab, reputed to be handling two-thirds of his revenue and earning the princely sum of Rupees 40 lakhs a year (Rs 369 crores today). Another prominent Hindu was Rai Durlabh, the Nawab’s Diwan or finance minister. Less well known was a notoriously crooked Sikh businessman called Omichand, described as “everyone’s idea of the worst sort of Indian tycoon, immensely rich and infinitely slimy,” one of the largest landlords of Calcutta and agent for the Company’s annual “investment” in Bengali products for export to Europe. And then there was Nandkumar, the wily Brahmin faujdar of Hooghly fort, guarding the access to Calcutta.

What followed over the space of a year was a complex web of intrigue designed to replace Siraj with a Nawab who would be compliant with both the Company and the Hindu business community. The latter’s commercial interests were firmly tied to the Company’s trade, which had suffered due to Siraj’s attack on Calcutta. Historians have also pointed out that the Mughal-style court of the Nawab of Bengal, made up mostly of Turks, Arabs, Iranians, Armenians, Afghans and Central Asian Muslims was every bit as aloof from and alien to native Bengalis as the white traders of the various European companies.

Plan to replace Siraj

As the months rolled by, what had originated for Robert Clive as a punitive expedition against the Nawab gradually matured into a plan for regime change and eventually, East India Company usurping the Nawab’s role altogether. But it’s significant that Clive never envisaged overthrowing the Mughal constitution of India or rejecting Mughal overlordship.

The plan to replace Siraj originated with Omichand, who apparently told Clive’s envoy that this Nawab could never be trusted or trusting. The Seths too made mischief between Siraj and the Company, even warning the British Resident that Siraj wanted to impale him, while inciting the Nawab himself to anti-British outbursts.

The next step was to enlist the support of the Mughal nobility led by the Nawab’s relative, Mir Jafar, the paymaster of his troops. After protracted negotiations, Clive concluded a secret treaty with Mir Jafar, whereby the latter was to become Nawab in place of Siraj in return for large payments to the Company and to Clive himself.

Clive was roundly condemned by Macaulay for a ruse whereby the crooked Omichand was duped by being shown a forged copy of the treaty, promising him an inflated sum of the prize money actually due, Rupees 30 lakhs instead of 20. “This man, in other parts of his life an honourable English gentleman and a soldier,” Macaulay wrote, “was no sooner matched against an Indian intriguer, than he himself became an Indian intriguer, and descended, without scruple, to falsehood, to hypocritical caresses, to the substitution of documents…”

The plot thickened when Siraj and Mir Jafar suddenly had a public reconciliation, sworn on the Quran. Jafar wrote to Clive admitting the reconciliation, while reassuring him that “what we have agreed on must be done.” There followed what the imperial historian, Philip Woodruff, described as “the most miserable skirmish ever to be called a decisive battle.”

Money after Plassey

The Battle of Plassey, 1757, which marks Clive’s defeat of Siraj and the founding of British rule in India, turned out to have been no more than a rout for the Nawab’s huge but unwieldy army, while the main troops, led by the duplicitous Mir Jafar, looked on in glee.

Clive’s share of the booty, paid out of the new Nawab’s rapidly depleting treasury, amounted to the large sum of £234,000 (£24 million today), even though he turned down additional bribes from the Nawab’s advisers. “Though we think that he ought not in such a way to have taken anything,” wrote a disapproving Macaulay, “we must admit that he deserves praise for having taken so little.”

Clive himself later told a Commons Select Committee at Westminster that he marvelled at his own moderation, given the opportunities for massive corruption and plunder in a subcontinent accustomed to being looted by successive waves of Persians, Afghans and Marathas. “Jagat Seth and several of the great men, anxious for their fate, sent their submission, with offers of large presents,” Clive admitted, and went on, “The Hindu millionaires, as well as other men of property made me the greatest offers…and had I accepted these offers I might have been in possession of millions… but preferring the reputation of the English nation, the interest of the Nawab, and the advantage of the Company to all pecuniary considerations, I refused all offers that were made to me.”

Also read: Like Rahul Gandhi, British in India viewed chowkidars as ‘chors’ too

Corruption and depletion of Nawab’s treasury

Clive had two terms as the Governor of Bengal. The first, lasting three years after his victory at Plassey, was unremarkable, except for the protection he extended to Hindu grandees from petty tyranny by the new Nawab, Mir Jafar. The Nawab’s Bihari deputy, Ram Narayan, in his gratitude even likened Clive to Christ. Less savoury was Clive’s tolerance of the greed of his fellow countrymen.

The new regime was marked by several years of monopolistic private internal trade carried on by the Company’s servants, to an extent that depleted the Nawab’s treasury of its revenues and threatened even the Company’s monopoly on foreign trade. The Dual System over which Clive presided had accepted the nominal overlordship of the Mughal emperor and his deputy, the Nawab, to whom the tasks of revenue collection and administration of justice were relegated. It was a pragmatic, transitional arrangement necessitated by the fact that the East India Company had as yet no trained civil servants of its own. “You seem so thoroughly possessed with military ideas,” the directors had written to Clive after Plassey, “as to forget your employers are merchants and trade their principal object…”

The once thriving economy of Bengal suffered both from the instability of recurring palace coups and the supplanting of established Indian merchants by gomustas of the English traders. “The servants of the Company obtained…a monopoly of almost the whole internal trade,” Macaulay later lamented. “They forced the natives to buy dear and to sell cheap. They insulted with impunity the tribunals, the police and the fiscal authorities of the country. They covered with their protections a set of native dependants who ranged through the provinces, spreading desolation and terror wherever they appeared. Every servant of a British factor was armed with all the power of his master; and his master was armed with all the power of the Company.”

Clive’s absence from Bengal and misgovernment

In Clive’s mitigation is the fact that the Company he served had been suddenly catapulted into a position of political power, which was entirely novel and unprecedented. A remarkable letter from Clive to Pitt the Elder in January 1759 contained the germ of the future British Raj. Clive told Pitt that he could easily have won Mughal recognition for himself as Nawab, instead of Mir Jafar, and held out the prospect of the British Crown taking over India, as a trading company was obviously unfit for the challenge.

Historians have agreed that the worst excesses by the Company’s nabobs occurred without Clive’s support and after his return to England. Much as he disapproved of the anarchy he left behind, Clive’s two-year term was far too short to bridge this transitional period, and his ambitions were again focussed on Westminster when he returned to England in 1760. The great jurist and Sanskritist Sir William Jones summed up this period with the metaphor that Bengal, like an over-ripe mango, had “fallen into England’s lap while she was sleeping”.

Clive’s five-year absence from Bengal is generally regarded as a period of unparalleled misgovernment and rampant corruption. Clive himself spent these years in London, lobbying both the Company and Parliament for recognition of the lucrative jagir, worth £23,000 a year (£2.4 million today), that he had been awarded by Mir Jafar, in recognition of the rank of Mansabdar conferred on him by the Mughal emperor.

Legendary military prowess

Back in London, Robert Clive was again warmly received by both the King and his ministers, and his military prowess became legendary. George III, when asked if a young nobleman should train under Frederick the Great of Prussia, advised: “If he want to learn the art of war, let him go to Clive”. Pitt the Elder, later Earl of Chatham, echoed the King, describing Clive in Parliament as “a heaven-born general, as a man who, bred to the labour of the desk, had displayed a military genius which might excite the admiration of the King of Prussia.”

His Indian jagir and its income, remitted back to England, were to prove a guarantee of both Clive’s wealth and his security from reprisals by his critics. He was very generous, we are told, in handouts to friends, family and political allies. He was elected to the House of Commons in 1761, at the head of his own faction of seven members, and also played a major part in the East India Company’s very turbulent Court of Proprietors. Clive had shrewdly bought up £100,000 worth of Company stock (£10 million today), which he then split under the names of numerous shareholders whom he controlled, thereby giving his faction a majority. The proprietors and the directors were accordingly prevailed upon to accept his jagir.

Corruption, the battle harder than Plassey

Meanwhile, back in Bengal, a conflict between the Company and an assertive new Nawab, Mir Kasim, who had succeeded pliant Mir Jafar, had escalated into open warfare, the Nawab joining hands with his fellow Nawab of Oudh and the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II in a formidable triple alliance. By 1764, with Bengal descending into chaos, Clive was seen as the only man who could restore the Company’s fortunes. He agreed to return to India on the one condition that Laurence Sulivan, the East India Company’s powerful chairman and his inveterate opponent, was removed from his post. A friendly Court of Proprietors obliged, and Clive promised in return to accept no more emoluments, now that his beloved jagir was secure.

The poacher had most definitely turned gamekeeper. Clive had been shocked by the effective sale of Bengal’s throne on the death of Mir Jafar, with nine leading Company officials receiving a bribe that totalled £140,000 to install Jafar’s infant son as nawab. Clive wrote to a friend: “Alas, how is the English name sunk! …. I do declare …that I am come out with a mind superior to all corruption, and that I am determined to destroy these great and growing evils, or perish in the attempt.”

Writing to a Council member on his way back to Bengal in 1764, Clive announced: “What an Augean stable there is to be cleansed. The confusion we behold, what does it arise from? Rapacity and luxury, the unreasonable desire of many to acquire in an instant what only a few can, or ought, to possess…in short, the evils, civil and military, are enormous, but they shall be rooted out.”

The war on corruption became his constant refrain for the next 18 months, while Clive fought what he described as “a battle far harder than Plassey”. Under his close watch, the Company’s officers were now strictly prohibited from receiving presents or from private trading. Their corruption was rooted in their low salaries, set by the directors, which Clive couldn’t alter. So, he came up with the ingenious idea of creating a Company monopoly on salt, which its servants could use to supplement their salaries.

Having secured his own fortune, Clive stood firm against rebellions from his officials, including a mutiny in his army. He strictly adhered to his own rules and accepted no more gifts, shunning lavish offers of jewels from the Raja of Benares and the Nawab of Oudh. He did accept a legacy of £60,000 (£5 million now) left to him in Mir Jafar’s will, but publicly paid it over to the Company, to be used specifically for the care of officers wounded in its service.

Flower of the empire, Defender of the country

Clive’s second governorship came after the Battle of Buxar, far more decisive than Plassey and fought in his absence. Receiving the fugitive Mughal emperor as a supplicant pensioner, Clive showed his mastery of political theatre in setting him up on a makeshift throne in his own tent and formally receiving from him the Diwani or finance ministership of Bengal. It was an arrangement that put an end to the failed Dual System of power-sharing with effete Nawabs and firmly recognised the Company as the government of Bengal, collecting its revenues, managing its trade and organising its finances. Clive had no compunction about the acceptance this involved of Mughal sovereignty.

Rightly believing that Indians were impressed by the trappings of power, the Company’s Bengal Governor now allowed himself to be festooned with Mughal titles such as “Flower of the empire, Defender of the country, the brave, the firm in War”. Notwithstanding such acceptance into the Mughal hierarchy, a striking feature of his second governorship was his continued alliance with Bengal’s Hindu business elites, whom he openly preferred to those he termed “fat, expensive Moormen”.

His closest associate was a Bengali Brahmin called Nabkishan, who rose from being one of Clive’s translators to his unofficial right hand. Nabkishan, we are told, spoke fluent English and built himself a palatial Calcutta home, where he entertained European style, unlike other Hindus, with Governor Clive a frequent dinner guest. Nabkishan was heartbroken when Clive returned to England for good in 1767. Although rewarded with the title of Maharaja by the Mughal emperor, he was targeted by Clive’s Calcutta enemies and accused of various offences, including being a “catamite”, all of which were found to be fabricated.

Clive’s second governorship had ended with another bout of his combined nervous and gastric disorder, compounded by malaria and the tropical climate. In any case, his sights had always been set on Westminster, where he hoped to enter the Lords as a British peer. Macaulay later wrote an even-handed verdict on his second Indian proconsulship:

“When he landed in Calcutta in 1765, Bengal was regarded as a place to which Englishmen were only sent to get rich, by any means, in the shortest possible time. He first made dauntless and unsparing war on that gigantic system of oppression, extortion and corruption. In that war, he manfully put to hazard his ease, his fame and his splendid fortune. The same sense of justice which forbids us to conceal or extenuate the faults of his earlier days compels us to admit that those faults were nobly repaired.”

But Clive’s enemies judged otherwise.

A scapegoat

When Robert Clive returned to England for good in 1767, it was to face both the bitter rancour of those who had suffered from his war on corruption and also persecution by those who saw him as symbolising those same hated nabobs. “The very abuses against which he had waged an honest, resolute and successful war, were laid to his account,” wrote Macaulay. “He had to bear the double odium of his bad and his good actions, of every Indian abuse and of every Indian reform”.

Clive’s two-year, second governorship had been far too short to complete the drastic reform he had begun, to turn the Company and its servants from monopolistic traders into a professional civil service running a territorial empire. It was a process taken much further under his able successor, Warren Hastings. Meanwhile, Clive was lampooned in the British Parliament and press for crimes ranging from his expensive tastes, such as ordering two hundred of the finest shirts from his London tailor, to having caused the severe famine, which hit Bengal in 1770, three years after his departure. Famine historians agree that it was basically due to one of Bengal’s chronic monsoon failures, although monopolistic trading by the Company’s employees and their native gomustas probably exacerbated speculation, hoarding and failure of supplies.

Clive was wrongly blamed for such disasters, even though he was back in England and had prohibited private trade by Company servants. The horrors of the Bengal famine and exaggerated rumours of speculation by Company servants were widely reported and believed back in England, not least by Company shareholders who saw their investments evaporating. Not surprisingly, they turned on Clive, who had shrewdly sold most of his own Company stock while prices were artificially high due to exaggerated estimates of the wealth of Bengal.

Part of the problem was his role as a convenient scapegoat for the Company’s own unpopularity in British political circles, caused by its ventures into parliamentary politicking and exaggerated public notions of the influence and wealth of its India-returned nabobs. Clive, despite his close connections with the King and his ministers, was doomed never to receive an English peerage and had to content himself with an Irish barony and his proudly worn Order of the Bath. He nevertheless played an important part in the process that would turn his beloved company from the preserve of private proprietors into the world’s first public-private partnership, administering Britain’s newly acquired Asian possessions and accountable to the British Crown and Parliament.

Also read: Proved by science: Winston Churchill, not nature, caused 1943 Bengal famine

The Regulating Bill of 1772

The new system was laid down in the Regulating Bill of 1772, enacted a year later, which was to be the first of several successive charter renewals for the Company, accompanied by growing public control through its government-nominated Board of Control and its appointees among the governors and their councils on the ground in India. Clive, re-elected to the House of Commons, was a member of its Select Committee set up in 1772 to hear evidence about the Company’s disorders and devise remedies.

Although a member of the Committee, Clive had to submit to being cross-examined by his colleagues about his own record as Governor of Bengal, the gifts he had received and his attempts to prevent private trading. He later complained that the Committee had treated him “like a sheep-stealer”, but exonerated him of most accusations and incorporated most of his ideas in the Regulating Act of 1773. In particular, Clive could claim the credit for turning the governorship of Bengal into the post of Governor-General, with supreme authority over the presidencies of Madras and Bombay, and for a strict ban on private trading or the acceptance of gifts by Company servants. It was a reform that enabled successive Governors-General like Warren Hastings, Lord Hastings and Lord Wellesley to make British power paramount in the subcontinent, based not only on military force but on an increasingly idealistic and incorruptible civil service and judiciary.

Clive’s speech to Parliament supporting the Regulating Bill was described by master-orator Lord Chatham, once himself a great parliamentarian as Pitt the Elder, as “one of the most finished pieces of eloquence ever heard in House of Commons”. “Had not his voice suffered from the loss of a tooth,” Chatham commiserated, “he would be one of the foremost speakers in the House. In fluency he has scarce an equal; in a speech of three hours hesitating less than any person could imagine. His delivery is bold, spirited, but yet gracious.”

A penknife for misery

How Clive’s career might have progressed under the new regime is hard to predict. A hostile newspaper had described him as “an obscure urchin, picked up, fostered and very unmeritedly raised to the highest pinnacle of affluence and pageantry by that deluded Company.” On the other hand, his admirers, including the royal family, revered him as the man who had won Britain an empire that would soon compensate for the loss of its American colonies. His role as imperial proconsul was summed up by a marble statue of him, robed in a Roman toga, erected in the main hall of the Company’s headquarters at India House in the City of London.

Clive’s character offers some parallels with that of another controversial British icon, Winston Churchill. Like Churchill, Clive had enormous intelligence, an ability to get things done and inspire others, a capacity for both hard work and interludes of hedonism and, less fortunately, for petty quarrels. With the passage of the Regulating Act, there’s every likelihood that he might have led the new Board of Control it set up at Whitehall, eventually also achieving the English peerage he so coveted.

Instead, 1773, the year of the Regulating Act, saw Clive relapse into a bout of depression, a malady he shared with Churchill, accompanied by his familiar abdominal cramps. Clive was playing a game of whist with his beloved wife Margaret and some guests at their Mayfair home when he rose abruptly, excused himself and disappeared into his bedchamber. Searching for him when he failed to return, Margaret found him seated on his water-closet bleeding to death. In a paroxysm of physical pain and psychological distress, he had stabbed himself in the jugular with a humble penknife. It was a tragic end to a great man tormented by his demons. He was only 49.

The author has a doctorate in history from Oxford and is a historian and broadcaster. His books include biographies of Indira Gandhi and Lord Macaulay. Views are personal.

This article was originally published on The Article.

Very interesting article and wonderful comments. There is a debate in Shrewsbury, England, regarding removal of Clive’s statue in the town.

Brothers were criminals, Mafia….. All agreed during East India times in India. They looted, plundered, caused immense daily exploitation,. Agreed. Some work which the generations enjoyed and continue so are Develoment of Lord Maculays Education system, that Indian Govt operates in our Schooling and university systems, since Lord mscaulay introduced in his reign. Brits also developed, Railways, Coal mining, crude oil in Assam Digboi town, postal system, Administration, law and order, Police, Armed forces, civil services, Medicine, Motor vehicles, transport, roads, ports, trade, commerce, irrigation in agriculture, Rationalisation of land records, Land revenue, allotment and sale purchase of land via Tehsil and District registry mechanism, during Mughal and before mughal, Indian Kings, no one had developed anything but developed their wealth and did enjoy…. This is reality. Some blame Britishers for all the ills. Some blame Mughals and earlier plundered from Turky, Iran, Afghans, Arabs,… Some blame the Indian Kings that ruled before the invadors….. The best out of worst were Britishers who did lots of overall development of this country even though Britishers also caused the bengal famine by Churchill caused millions death.. Horrible.. Shameful.

We have wasted much of our time the created history of these British officers Clive and Hastings. British certainly glorifies them. There is no point in reading about them in school syllabus which is of no practical value. It is up to someone who wants to do research on these guys.

In fact even in England Clive etc. find no mention in the school syllabus. In fact there are no references to Britain’s colonial past in the school syllabus anywhere in the U.K. The reason is not far to seek. Irrespective of how their credentials are sought to be burnished, most of them were buccaneers, charlatans, thieves, exploiters and warmongers. Even modern Britain realises this and wishes to disown/erase their shameful past by removing any references from current history syllabuses.