South Asia is back in US reckoning, front and centre, not just with India and Pakistan committing to peace on the Line of Control, but US Secretary of State Antony Blinken this weekend making an important move on the Afghanistan chessboard.

Days after the LoC fell silent, Blinken wrote to Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, suggesting senior Afghan leaders should hold face-to-face discussions with the Taliban as well as involve the UN in organising a conference on Afghanistan, in which India will also likely participate.

Certainly, Blinken’s letter is a major vote of confidence in India’s staying power in Afghanistan. These past two decades, New Delhi has refused to be baited by Pakistan next door for not being an immediate neighbour to Kabul, overcome the geographical disadvantage by opening its doors to thousands of Afghan students, ramped up its interest in the Chabahar Port in Iran to circumvent Pakistan and send goods via Iran, and kept in close touch with all shades of the Afghan leadership.

(An anecdote is in order here. In an effort to also attract young Afghan female students who wish to study in India but don’t get permission from their conservative families to travel and live alone, Indian diplomats have sometimes bent the rules a little by also giving scholarships to their fiances and brothers.)

So over the last year, even as the pandemic raged, India turned around its policy on Afghanistan in order to be present at the table when the big boys dealt the cards. Only in 2018, when Moscow had invited an Indian delegation to participate in a consultation with the Taliban, the Indian team had been given express instructions not to talk to them at all.

Also read: Biden’s first security plan shows US desperate for partners. But India must read fine print

Talking it out with the US

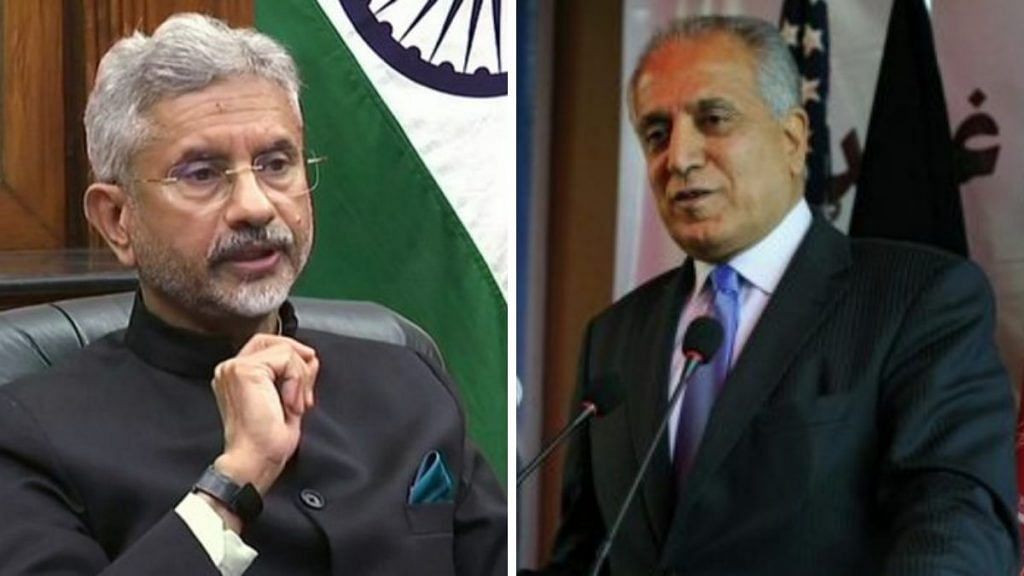

Last September, External Affairs minister S. Jaishankar addressed the inaugural peace talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government in Doha. It was an assertion of several decisions.

First, India would not remain on the sidelines even when it abided by the “Afghan-led and Afghan-owned peace process” underlined by President Ghani, that was also intended to keep himself in the limelight. Second, if the US was bringing Pakistan back into the peace talks because it was the only country with the influence to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table, then that was a message to Delhi too: Talk to the Taliban. Don’t marginalise yourself.

There was a third assertion. Despite its weakening, US influence in Afghanistan would remain second to none for a long while to come. As part of the growing India-US partnership, Jaishankar decided to reach out to the US also on Afghanistan.

Despite the huge divergence in their positions, Jaishankar realised that it was important to be seen to be holding Zalmay Khalilzad’s hand. So when Donald Trump’s special envoy — and now Joe Biden’s — came to Delhi just before the pandemic grew out of control, Delhi rolled out the red carpet.

What Khalilzad wanted was somewhat different from Jaishankar’s expectations. Khalilzad wanted Delhi to not put spokes in Taliban’s return to the peace table with the Afghan republic, but continue to support the economic reconstruction of Afghanistan.

Delhi wanted Khalilzad to open his eyes and smell the coffee about Pakistan not changing its stripes. It wanted to remind him that Pakistan had not kept the Taliban on a tight leash in various Pakistani towns such as Quetta and Miranshah since 2001, only to now abandon its intention to control the throne of Kabul.

But Jaishankar understood the unspoken plight of the Americans. The world’s most powerful nation was declining and it wanted to get out of the longest war it had fought – longer than Vietnam. Thousands of American soldiers had died, more than $2 trillion spent. Worse, the US was not on talking terms with Iran, Europe was too far away, Russia was a competitor and China wasn’t showing its hand.

Even if India was the good guy, it was too weak to shape the politics of the region. What should it do to make itself relevant again? It was a question that had even fewer answers as the Chinese climbed the icy heights of Ladakh.

Also read: Jaishankar speaks to US special envoy on Afghanistan, takes stock of Taliban peace talks

And moving in the neighbourhood

Back in Afghanistan, Delhi’s policy of maintaining a deep and special friendship with the Afghan people has kept it in good stead. This policy of strategic patience was forged under the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government in 2001 after the Taliban were overthrown; it continued during the Manmohan Singh decade and has been reinvented under Narendra Modi. It has ensured that New Delhi won’t be ignored when the dice is rolled on the Afghan table.

Significantly, Jaishankar hasn’t sat on his hands waiting to be invited by the Americans to play a role. He has reached out to Afghanistan’s neighbours, several of whom have had unhappy or no ties with the US. In Russia, India and Iran have attended a trilateral meeting on Afghanistan. Iran’s defence minister came to the airshow in Bengaluru. Delhi keeps in close touch with Russia’s special envoy Zamir Kabulov, although Kabulov seems more than a little contaminated by America’s fascination for Pakistan.

The change of guard in Washington DC has made it clear that the road from Delhi to Kabul must take Islamabad into account. That’s why talks to renew the LoC agreement began in October, on the eve of the US presidential election, when it was clear that Trump was waning. Media reports are conflicted about whether National Security Advisor Ajit Doval met Pakistan army chief Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa or special assistant to PM Imran Khan on national security, Moeed Yusuf. There is speculation that a face-to-face meeting took place in Colombo.

Certainly, the discussions are imbued with a sense of pragmatism. Pakistan has come to terms with the fact that it must move on from its unhappiness over the abrogation of Article 370 and the integration of Jammu and Kashmir into the Indian Union.

Similarly, the Modi government has taken an about-turn on returning to talks with Pakistan without cross-border terrorism coming to an end. The disengagement in Ladakh and the decision to keep the LoC quiet is proof that India did not want to keep both its fronts open.

For the time being, people on both sides are holding their breath. Slow and steady is the new mantra. Peace on the LoC must be consolidated. Assembly elections in India and political instability inside Pakistan – Imran Khan has been unable to get his finance minister Hafeez Sheikh elected to parliament, some say, because the Pakistan army indicated that Sheikh’s opponent was a better man – means that the next few months will be on slow fuse.

This will allow the India-Pakistan backchannel the space to talk some more. It is also enough time for the Americans to unveil their new strategy on Afghanistan and ensure that it gathers steam.

Views are personal.