India’s judiciary, like the other pillars of democracy, scores low on women’s representation.

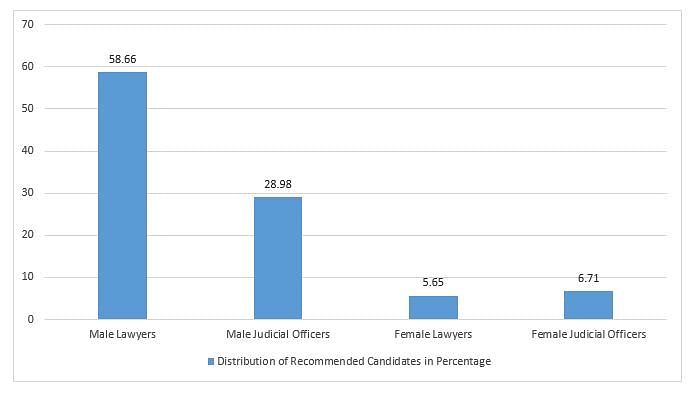

Over the course of 18 months, between October 2017 and April 2019, of the total number of candidates the Supreme Court considered for high court judgeship, 87.63 per cent were men while 12.37 per cent women. When we lament a homogenous higher judiciary, much of the problem actually starts with the high court collegiums as it is the high court collegiums that recommend candidates to the Supreme Court collegium.

Role of HC collegiums

In relation to the appointment of judges in high courts, while the Supreme Court collegium has the final authority, it cannot initiate the appointment process on its own. That responsibility lies with the high court collegium, which identifies the candidates and recommends names to the Supreme Court collegium to take a call. The Supreme Court collegium may accept or reject or return a recommendation but does not suggest a name to be added to the list. So, while the high court collegiums cannot ensure who becomes a judge, they have the power to ensure who does not.

Figure 1: Percentage of recommended candidates by HC collegiums

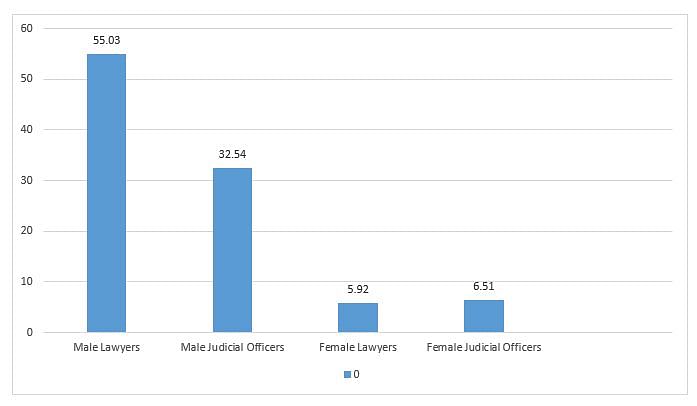

Figure 2: Percentage of accepted candidates by SC collegium

Most appointments approved by the Supreme Court collegium follow the pattern wherein candidates are recommended by the high court collegiums – 87.57 per cent of all accepted recommendations were male candidates.

Also read: Sexism in Indian judiciary runs so deep it’s unlikely we will get our first woman CJI

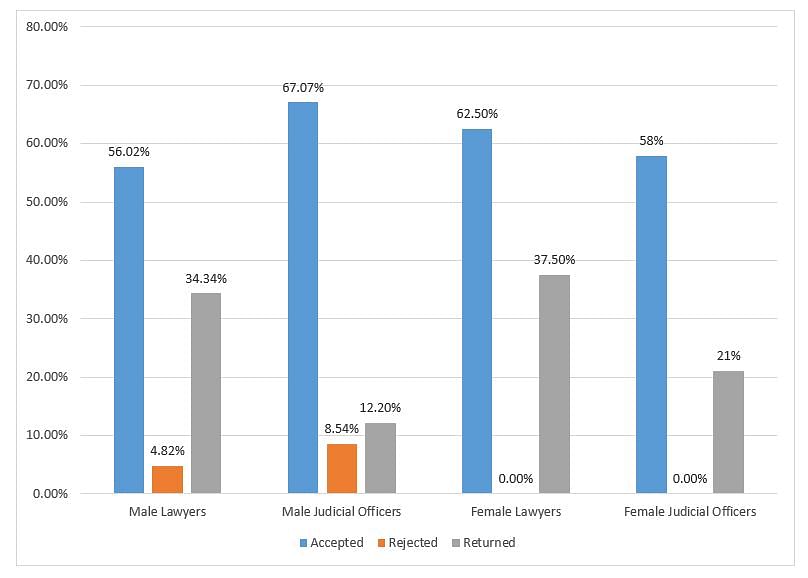

Figure 3: Pattern of decision for different categories of candidates

A preference for lawyers

This pattern of homogeneity is also seen in the high court collegiums recommending more lawyers over judicial officers and jurists for judgeship. Lawyers accounted for 64.31 per cent of the recommended candidates while 35.69 per cent were judicial officers. There was not a single jurist recommended by any of the high court collegiums.

But when it comes to rate of acceptance, lawyers, in relative terms, fare worse. The candidature of only 56.02 per cent of all recommended male lawyers was accepted by the SC collegium as against 62.50 per cent for female lawyers. Judicial officers, in contrast, have a higher rate of acceptance – 67.07 per cent for men and 58 per cent for women.

Also read: Women’s Day reality check: Less than 12% of judges in SC and high courts are women

All walk the same road

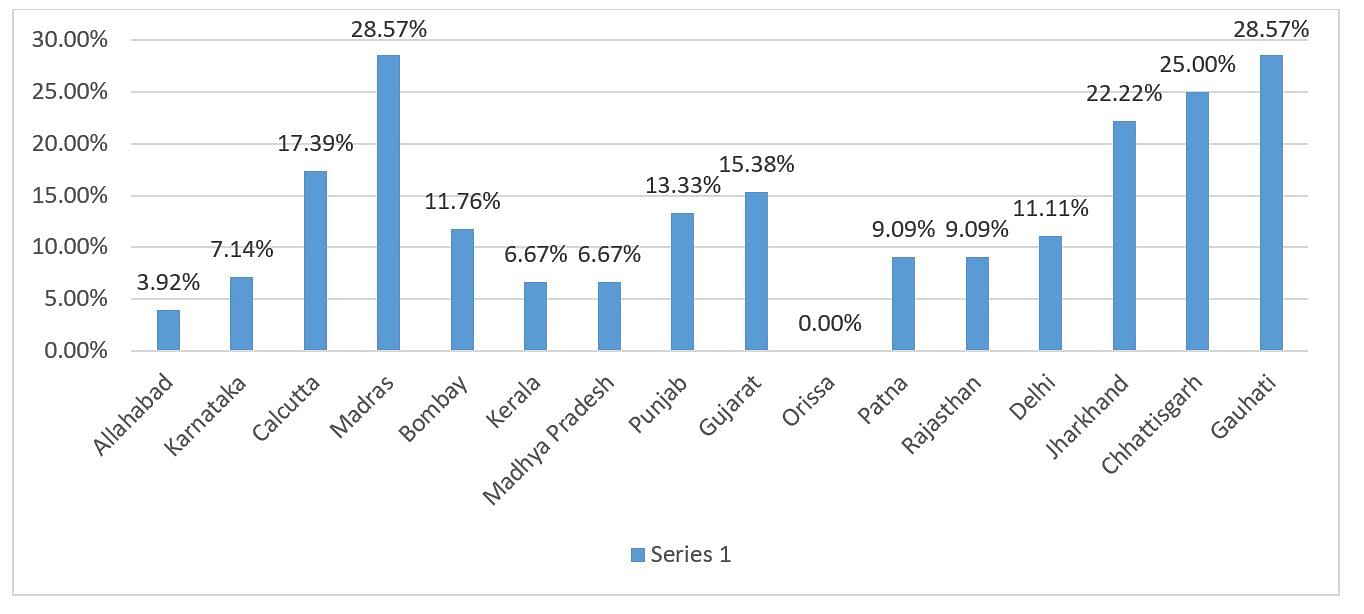

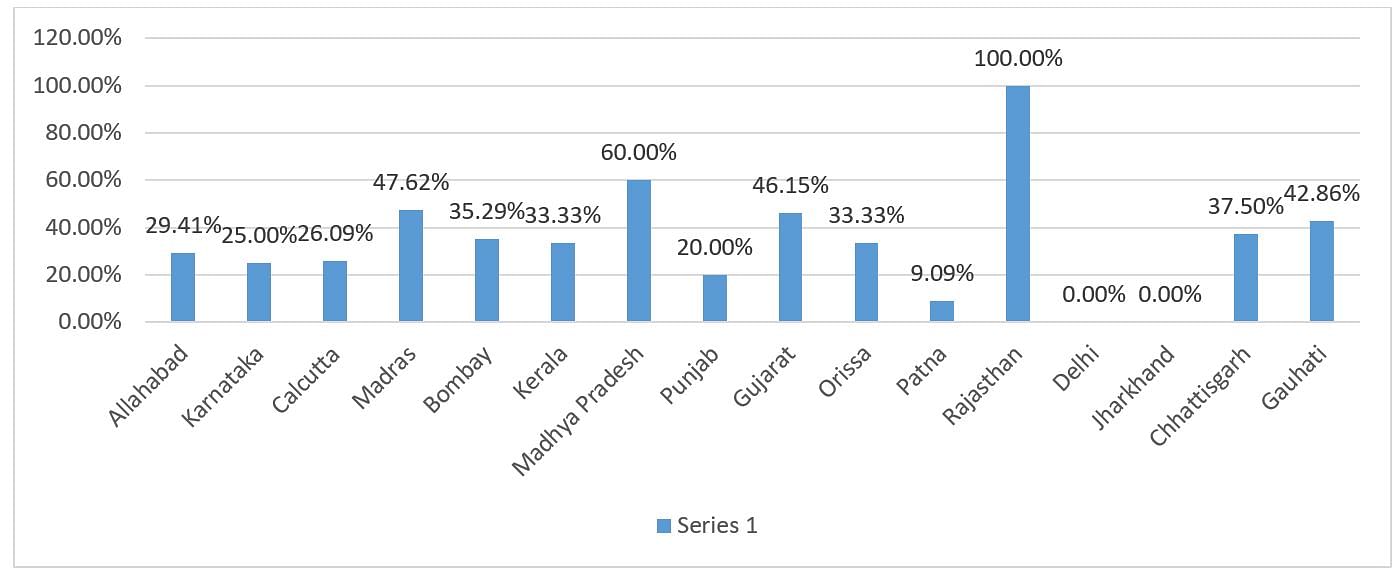

The numbers show that almost all high court collegiums are equally monolithic in their recommendation patterns. Not a single high court collegium recommended more than 30 per cent women for judgeship. For many high court collegiums, the number is below 10 per cent. Figure 4 shows the proportion of women candidates recommended by different high court collegiums that had more than five recommendations considered by Supreme Court collegium in the identified time frame.

Figure 4: Percentage of recommended women per HC collegium

The numbers are slightly more dignified for judicial officers. However, if we take out Madras, Rajasthan and Allahabad (although Allahabad in itself has a disappointing figure of 29.41 per cent), the percentage of recommended judicial officers from all high court collegiums drops from 35.69 per cent to 26 per cent. Figure 5 shows the proportion of judicial officers recommended by various high court collegiums that had more than five recommendations considered by the Supreme Court collegium in the identified time frame.

Figure 5: Percentage of recommended judicial officers per HC collegium

Reasonable explanation?

It is possible that there are just more qualified lawyers than there are judicial officers and more qualified men than women. But such an explanation would run contrary to the fact that the proportion of rejected/returned names for lawyers is higher than that of judicial officers. Similarly, the rate of acceptance is higher for women lawyers than their male counterparts. While the difference in the acceptance rate of male judicial officers and female judicial officers is only 9%, the difference in their recommendation figures is 22%.

It could be argued that there are not enough women judicial officers in positions of leadership in the subordinate judiciary and it reflects in the recommendation figures. However, that would also put the high courts under scrutiny as the promotion and career of judicial officers is under their direct supervision. It may be so that the recommendation figures are proportional to the total number of lawyers and judicial officers (male and female) in the respective states. It may as well be that the lawyers are allotted more judgeships pursuant to an informal understanding which is completely arbitrary and not based on any methodological foundation. It could be any of these reasons or none of these.

Instead of speculating, we would have a more informed understanding if the high court collegiums, following the lead of the Supreme Court collegium, publish the resolutions of their meetings.

Also read: Women lawyers don’t feel safe anymore in Supreme Court, says lawyer Indira Jaising

Commitment to transparency needed

Since 3 October 2017, the Supreme Court collegium has been publishing its resolutions on its website. The step was taken, in the collegium’s own words, to “ensure transparency of the collegium system”. This step was prompted, partly, by the realisation that the collegium system has been facing an acute crisis of legitimacy due to its opaque functioning.

While the published resolutions are definitively inadequate in spelling out the reasons behind the collegium’s decisions, the step to publish the resolutions has been a welcome one. The general public now has more information about the decisions of the Supreme Court collegium. Unfortunately, the high court collegiums have not found it prudent to initiate a similar practice.

The high court collegiums operate as the gatekeepers to higher judiciary. Without the approval of the high court collegium, a person cannot become a judge. Without a high court judgeship, it is extremely rare for a person to be appointed as a judge in the Supreme Court – 98 per cent of all Supreme Court judges who retired by May 2017 had been judges in the high court before their elevation to the Supreme Court.

The lack of diversity triggered by the high court collegiums keeps percolating across the system. Thus, it is important that we have a better understanding of the factors behind the monolithic pattern of recommendations by the high court collegiums.

The high court collegiums, ideally, should go a step further and not just publish their resolutions but also the reasons for selecting specific candidates. They should also share the pool of candidates considered by them as it would provide context to their selection. Our understanding of any selection process improves when the calibre of those selected can be compared to those who were not. If there has to be transparency in the appointment of judges in the higher judiciary, it should start with high court collegiums being more forthcoming about the manner in which they recommend candidates.

The author is Fulbright Post-Doctoral Research Scholar, Harvard Law School. Views are personal.

Perhaps the talent pool, from which recommendations can be made, is much smaller. A structural problem, which could take decades to resolve satisfactorily.