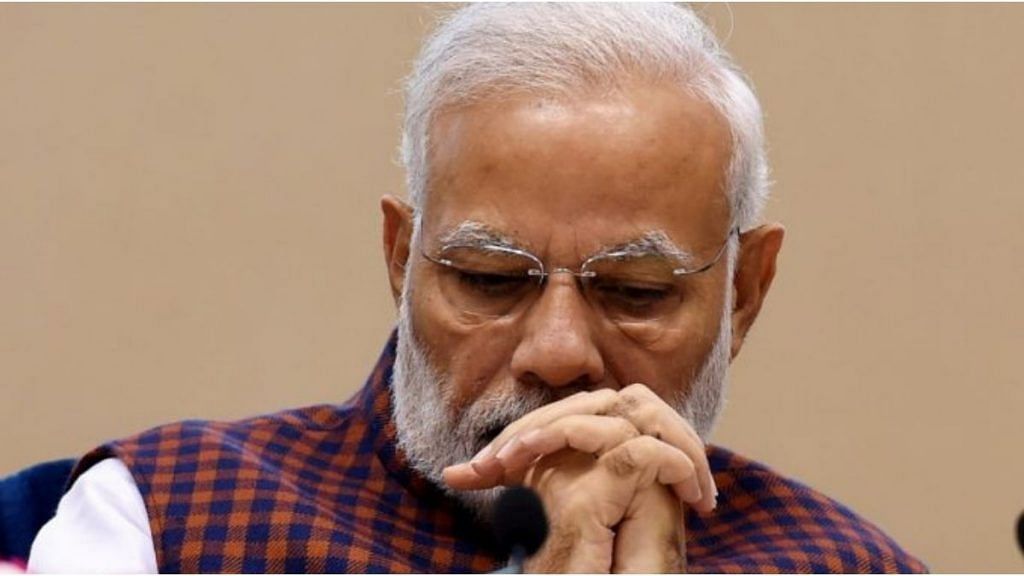

Even the most successful of politicians misjudge popular appetites and overreach. And they typically overreach when they overestimate the power of the very approach that brought them success. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s political approach is rooted in a Hindu middle-class universe — a blend of cultural essentialism, political majoritarianism, and economic aspiration — which shapes much of his politics. What the backlash over the three farm laws proves is that India is not, as of yet, that middle-class universe.

Modi’s narrative on the farm laws — of unshackling people from the chains of vested interests and giving them the path to prosperity — was perfectly in line with the politics that has repeatedly bolstered his popular support. A similar upending of status quo and quashing of entrenched interests were at the core of the popularity of schemes from demonetisation to Article 370 abrogation to the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) regime. The agricultural reforms push had all the features and sensibilities of Modi’s distinctive middle-class politics of aspiration. Yet this time, he seems to have misjudged the popular mood. What happened?

Fundamentally, what Modi has overlooked is that his middle-class constituency is essentially a coalition of two strikingly distinct classes — the traditional middle classes and the neo-middle classes. These two classes are bound together more by a sensibility and a loose ideological orientation rather than any concrete interests, and therefore, Modi’s middle-class politics is circumscribed by hard limits, which have become apparent now.

Also read: Art 370, CAA, triple talaq, Ram Mandir are just one cycle of Modi’s ‘permanent revolution’

The two middle classes

The traditional middle classes are the thin sliver of the population — the college educated and professionally employed people whom you see consuming English news and opining on social media. The neo-middle classes, a term popularised and politicised by Modi, are all the huge masses of people who have escaped poverty and self-identify as middle class but have not yet reached middle class living standards. As political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot had noted in 2014, it were the neo-middle classes which had powered Modi to victory.

The political brilliance of Modi has lied in fusing these two distinct classes in a politics of aspiration. This has given him a large area of catchment on which to base a dominant politics — 58 per cent of surveyors self-identified as middle class in a CSDS-Lokniti poll of 2019. Even Modi’s welfare policies towards the poor are framed under a middle-class modulated vocabulary of empowerment and development rather than as poverty alleviation schemes. In this political framework, when the expanded Hindu middle class comes together as one — such as on Article 370, Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), demonetisation, lockdown politics — it exerts a hegemonic force, which lends Modi the cloak of irresistibility.

However, as the furore over the farm laws shows, these two middle classes can sharply depart in political positions owing to different material interests. While the traditional middle classes have lauded Modi for the ‘politically tough’, ‘forward looking’ agriculture reforms, the position of the neo-middle classes seem to range from indifference or ambiguity to being openly opposed to the government actions.

This position of the rural neo-middle classes (at least) can be gauged not just from the mass protests at Delhi’s borders but even more so from the fact that no major party except the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is standing up for the farm reforms. Political parties, more than anyone else, have their ear to the ground and when the allies of the BJP and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s (RSS) own farmer wing openly support the protests, public opinion becomes fairly clear. Even its ally in Haryana, the Jannayak Janata Party (JJP), is being constantly pushed by its legislators to back the protests.

Also read: Modi faces no political costs for suffering he causes. He’s just like Iran’s Ali Khamenei

Middle classes’ State dependence and reform mindset

Rapid rise of incomes, urbanisation, and the spread of mass media had forged a common sensibility among this expanded middle class, a sensibility that pervades Modi’s politics. One part of it is political style — a managerial, de-politicised approach to governance, demonstrated in Modi’s disregard for Parliament and other constraining institutions, as was also witnessed in the passage of the farm bills. A 2005 CSDS poll found that 80 per cent of the upper-middle class felt that “all major decisions about the country should be taken by experts rather than politicians”. Similarly, a 2009 Pew survey among 13 countries revealed India to be the only country where the poor were more concerned about democracy than the middle classes. In all other countries, the middle class was the more progressive class.

The other part is a loose ideological orientation — such as favouring growth over redistribution and being allured by the politics of ethno-majoritarianism. As Nagesh Prabhu has argued in Middle Class, Media and Modi, this expanded and ‘hegemonic middle class’ lies at the heart of the Modi phenomenon.

However, what is often missed is that even though the ‘aspirational middle classes’ or neo-middle classes might share some of the same critiques of State corruption and State inefficiency as the traditional middle classes, that does not necessarily make them votaries of economic reforms, especially because it affects their own interests.

As political scientist E. Sridharan had demonstrated, a majority of the broad middle classes (58-75 per cent at the turn of the century) are either public employees or rich peasants that were themselves dependent on State subsidies. Therefore, unlike Western countries where the middle classes advocate economic reforms that cut subsidies for the poor, in India, much of the middle classes are themselves dependent on the State.

In fact, the ongoing protests in Punjab and Haryana were initially led by rich farmers who would ordinarily be assumed to support an expansion of private economic opportunities. But they not only remain deeply invested in the minimum support price (MSP)-mandi infrastructure, they in fact demand an expansion of the MSP regime, and thus the role of the State in agriculture. Meanwhile, the smaller and marginal farmers, who have also joined the protests in large numbers, seem even less enthusiastic at the prospect of being left to negotiate with big agricultural interests.

Therefore, the middle-class lenses of politics applied to the countryside, which assumed that the promise of less State regulation and greater economic freedom would attract the support of certain entrepreneurial classes of farmers, has shown itself to be unmoored to reality.

This should not have come as a surprise. A Lokniti poll of 2014 showed that only 16 per cent of people engaged in agriculture were opposed to government handouts. Even more broadly, 45 per cent of all people supported government handouts as opposed to 20 per cent who opposed them. A more aspirational electorate is not necessarily equivalent to a more reformist electorate, at least in practice. In fact, the one “reform” where the middle classes and the neo-middle classes stood most firmly behind the government was demonetisation, which was rooted in populist rhetoric rather than in any economic philosophy.

Also read: Teflon Modi does not have one Achilles heel, but two

Modi’s misreading of constituency

Some commentators have argued that if PM Modi stands firm like Margaret Thatcher did with labour unions, he might emerge stronger from this episode. This is unlikely because India is not Britain of the early 1980s. Whereas the expanded Indian middle class is inchoate and bound together by sensibilities, the British middle class was also more coherent and bound together by interests. The interests of the skilled workers, managers and property owners that Thatcher cultivated and socially engineered into an expanded middle class were distinct from the unskilled workers that protested her rule. In this fight, Modi only has the numerically insignificant traditional middle classes by his side.

However, it is clear that Modi cannot back down without losing the messianic strongman image that is at the core of his appeal. What would be even worse is to disperse the protesters by force and generate an even more damning narrative. The course of action with the least political costs is probably to tire out the protesters and then wrangle a face-saving compromise. In any case, for the first time since 2015, Modi seems to have fallen off to the wrong end of a political narrative. And he got there by misreading the very constituency that has raised him to unparalleled heights.

The author is a research associate at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. Views are personal.