For 45 years, India and China never exchanged fire. So, why should 16 June 2020 go down as the date when an argumentative peace of many decades finally ended as the bloodiest skirmish in a long time.

There are two possible answers. Tactically, the Chinese want to assert their new positions that interfere with Indian movement along the Darbuk–Shyok–DBO road at the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The road enables India to deploy troops quickly. On the strategic front, China wants to play the longer game of deploying the salami-slicing model to obtain a position of dominance and extract concessions from India – without firing a shot. This is a model China has successfully deployed to impose its perception of geographical ownership – whether it’s at the LAC or the South China Sea.

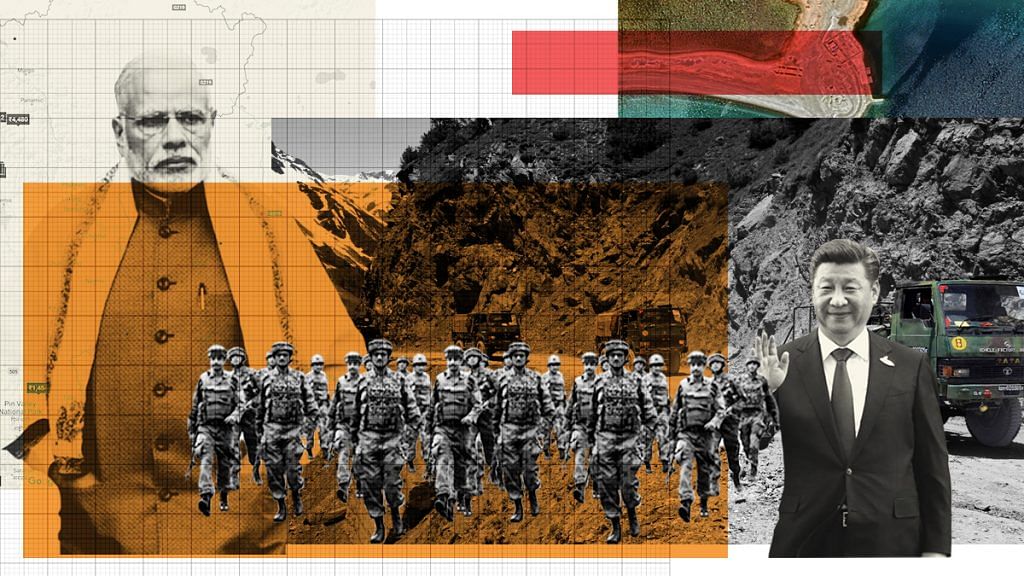

It’s interesting that this decade has witnessed more standoffs between India and China than the four previous decades collectively. It is no surprise that these standoffs have coincided with the emergence of President Xi Jinping and an assertive China. With each standoff, China has stepped up the intensity of its aggression.

The earlier standoffs at Daulat Beg Oldi and Chumar were of two-three weeks. Demchok followed in 2014, when Chinese troops had the audacity to threaten incursion even as Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping were signing agreements. Doklam in 2017 was a 73-day standoff to test India’s ability to protect its ally, Bhutan. India did not buckle down and China couldn’t get the mileage it sought. Given that China upped the pressure by a notch in each succeeding standoff, the current Ladakh deadlock, with a new issue raised at Galwan Valley, does not come as a complete surprise.

Also read: Modi-Shah’s Aksai Chin bravado activated China’s Ying Pai to cross LAC

India must change rules of engagement

So, what does India do at the tactical level? On previous occasions, in Nathu La in 1967 and in Sumdorong Chu in 1986-87 – as well as in Doklam in 2017 – India grabbed the ground initiative through local commanders, forcing China to retreat.

In the wake of the 16 June skirmish that cost the lives of many of its soldiers, India needs to show clarity in intent and firm resolve in communication to operate from a position of strength while dealing with China. If so many lives were lost despite familiar norms for unarmed conduct at the LAC, then the rules of engagement need to be revisited. Again, it is China that has changed the agreed norms of engagement – thus the onus is on India to drive the change. China has always chosen the points of skirmish in the past. The 3,488-km-long LAC, however, enables India to pick a ground of its own choosing to surprise China and put it under pressure.

By creating multiple pressure points in Ladakh, Naku La and Lipulekh, China has widened the span of engagement with India along the LAC. However, that too is at a tactical level. So, what is the strategic game plan?

Also read: India has a bigger worry than LAC. China now expanding military footprint in Indian Ocean

China’s surrogate conflicts

The story goes back to Xi Jinping’s ascension as premier in 2013. Two years later, in 2015, China released a military doctrine that named its threats and outlined an offensive-defence approach towards rivals. The US hegemony, South China Sea and Taiwan were named as major concerns but India’s watermark presence in American counterbalancing couldn’t be missed. Isolated in a Covid world of 2020, an insecure China must have pulled out the 2015 doctrine for a pre-emptive strike against its rivals.

A much downplayed India-Nepal issue on the sides of the Ladakh standoff reveals the future: the involvement of a Chinese ally against India is the new surrogate nature of India-China rivalry. When Nepal defied India and changed its map, it was a culmination of a political investment China had made.

In 2015, while a road blockade hampered relations between India and Nepal, China was busy investing in large projects in the Himalayan nation. By 2018, Nepal had signed on Chinese investments for eight important hydro projects. Similarly, in 2015, Sri Lanka borrowed $1.5 billion loan from China to build the strategic Hambantota Port. When it couldn’t repay the loan, China wrote off a large portion of the debt in exchange for a long-term lease on the port, much to India’s dismay. In South Asia, China capitalised on authoritarian governments in the Maldives and Sri Lanka to challenge India’s influence.

Of late, India has grown wary of the dragon’s ulterior objectives. When Sri Lanka’s Gotabaya Rajapaksa came to power in 2019, India’s S. Jaishankar was the first foreign dignitary to reach Colombo. Ibrahim Solih’s ascension to power in the Maldives ensured India regained its influence over China in the island nation. On Nepal, India enjoys stronger historical people-based ties over China, including Nepalese Gorkha soldiers who serve in the Indian Army. India’s restoration of ties with Nepal through Track-2 channels, thus, should be a priority. In a surrogate conflict, China wants to tie India down in the Himalayas and the neighbourhood.

Also read: PM Modi’s silence on LAC stand-off is benefiting China. India must change its script

Find the Achilles’ heel

How does India change its approach and leverage advantage? Recently, BJP MPs Meenakshi Lekhi and Rahul Kaswan ‘virtually’ participated in Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen’s swearing-in ceremony that left China fuming. During the LAC standoff, as Hong Kong grew vulnerable, Beijing opened reconciliatory lines to India through Sun Weidong, its ambassador in Delhi. For all its phlegmatic ruthlessness, China adopts a knee-jerk reaction when its pain-points are brushed.

In a world shaped by Covid-19, China struggles with an image deficit and disappearing allies. India has border disputes with 2-3 countries whereas China has disputes with a large number of countries – at its land borders and in the South China Sea. It is this Achilles’ heel that India needs to exploit as it finds itself in a pivotal space.

Increase China’s cost of interference

This is an opportune time for India to bring up Taiwan more aggressively, as Beijing changes its rules of dealing with India. As the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) finds itself wrapped in unpaid loans, debt traps and contradictions, a window of opportunity beckons.

Two years ago, Malaysia cancelled China-funded infrastructure projects worth $22 billion. India could explore the possibility of working closely with allies such as Japan for investments in countries such as Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and others. China’s defiance of multilateral agreements and continued belligerence in the South China Sea pits it against numerous adversaries. India will need to shed its neutral status and respond through active support towards countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines, which increases Chinese costs of interference in India’s backyard.

Around 80 per cent of China’s imported energy needs pass through the chokepoint of the Strait of Malacca in the Indian Ocean. China’s disadvantage with long sea lines of communication is an opportunity for India. In an expanded maritime role, India would need to increase its naval budget and strengthen the base in Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Similarly, proactive involvement in QUAD, D10 and other strategic alignments will give India the role it will need to put China under pressure.

Ladakh has shown China’s aversion to existing peace arrangements. To obtain greater leverage on its disputes with China, India will need to set up new terms of peace by shifting the goals of conflict elsewhere that cause discomfort to China. What India decides against China will define its global influence in a post-Covid world order.

The author is a former Army officer and author of Watershed 1967: India’s Forgotten Victory over China. Views are personal.