Which Bhagat Singh do we celebrate today? How do we resist the appropriation of the young revolutionary’s image and imagery? Can we rescue his memory from meeting the same fate as Mahatma Gandhi’s? Pondering over these questions is arguably the best way to mark his martyrdom day on 23 March.

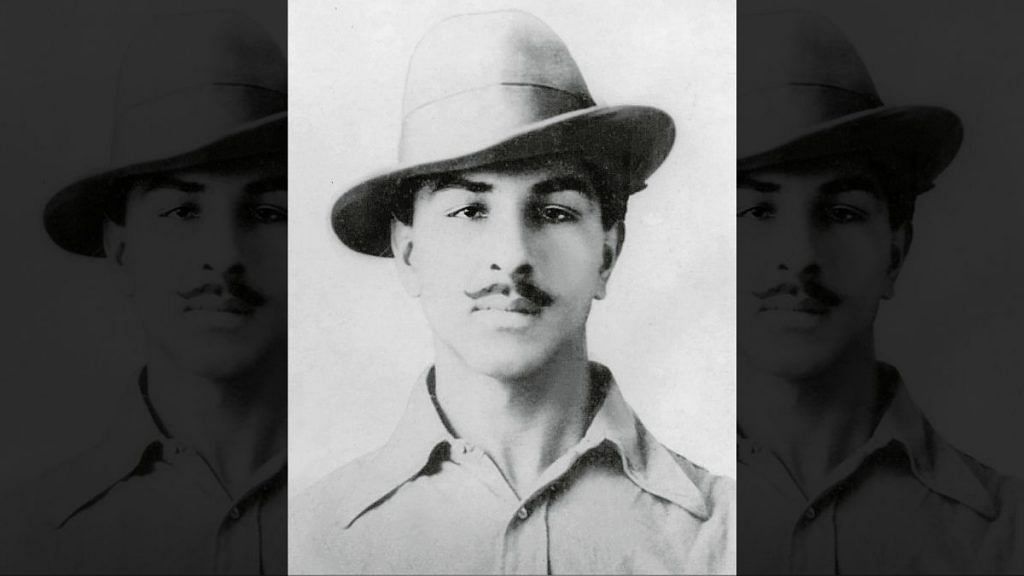

These questions jumped up in response to the new iconisation of Bhagat Singh by the newly elected Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) government in Punjab. On the face if it, the dispute was trivial. Bhagwant Mann, the new chief minister, put up a stylised image of Bhagat Singh (along with Babasaheb Ambedkar) that shows his weaving a basanti turban. Mann himself wears this turban and has popularised it over the last few years. He also invited all the Punjabis to join him in basanti colour on the day of his swearing in at Khatkar Kalan, Bhagat Singh’s ancestral village. Historian Chaman Lal, who has worked relentlessly to collect Bhagat Singh’s writings, was quick to point out that the photograph was at variance with any of the four historical photographs of Bhagat Singh available to us. Some of his relatives also joined this objection.

Now, there was nothing demeaning about the image used by the Punjab CM. This calendar art image is attractive, if inauthentic. Unlike the previous controversy about the use of his other image – a clean-shaven, hat sporting person – there is no issue in this case about erasing his identity as a Sikh youth. There is a real, historic connect of revolutionary nationalists and colour basanti, thanks to the immortal song, mera rang de basanti chola. One could argue that there is no reason why memory of historic figures should be confined to authentic photos. There would be no art if we insisted on replication. Surely, family or followers cannot control the use of image.

Professor Jagmohan Singh, one of Bhagat Singh’s grand-nephews, put the matter in perspective by saying that it is not about Bhagat Singh’s photograph, but about his ideas. That is the heart of the matter. That is why the dispute is deeper than it appears. The unstated objection is to political appropriation of a hero.

Punjab govt. should not use any imaginative illustration of Bhagat in govt. Offices. I urge Punjab CM @BhagwantMann to chose any of four original pictures which are available in public domain. pic.twitter.com/wfpZZWOAom

— Raman Dhaka (@RamanDhaka) March 15, 2022

Also read: Shaheed Bhagat Singh, the freedom fighter everyone loves

An icon undiminished by time

Bhagat Singh is one of the few nationalist icons who have aged well. Over-use and organised slander has smudged the image of Nehru and, to a lesser extent, Gandhi. No matter how hard his followers try, the truth of Savarkar’s life comes in the way of raising him to an iconic status. Babasaheb Ambedkar is among the few leaders of modern India whose stock has gone up in recent times. Of late, his image has begun to transcend the social limits in which it was entrapped for long. Unsurprisingly, his is the other image mandated by the new Punjab government.

Bhagat Singh stands out as an icon undiminished by time, not confined by geography, not captured by any caste or community, not dulled by official celebrations. Will he also turn into an icon untouched by his ideology and his politics? That is the real challenge today.

Bhagat Singh’s continued attraction — his image still stirs the youth, cutting across all divides — is precisely what makes him an attractive object of appropriation. This is not new. The iconisation of Bhagat Singh began in his own lifetime and has continued since. He has remained a symbol of militant nationalism that stood in opposition to the Gandhian mainstream. The Left tried hard but with limited success to keep alive the image of Bhagat Singh, the communist, the atheist, who read Lenin till the last day of his life.

Gradually, our historic memory of Bhagat Singh has thinned into that of a generic all-purpose nationalist. We remember him as an idealist who made the supreme sacrifice for India’s freedom, without bothering to find out about India he dreamt of. We hold him as a model for the youth, pure josh and little else, quietly forgetting that he wanted the youth to take to politics. We call him revolutionary, diminishing the idea of revolution to any and every form of radical change undertaken for any purpose. What we witness today is the culmination of a long process of de-radicalisation. This is what makes Bhagat Singh available to Congress, despite his trenchant critique of its politics, to the Akalis eliding his avowed atheism and, worst of all, to the BJP erasing his contempt for politics of Hindu nationalism in his times.

AAP threatens to take this appropriation one step further. With its decision to install the image of Bhagat Singh and Babasaheb Ambedkar in every government office, we could see the rise of a sarkari Bhagat Singh. In that sense, Bhagat Singh may be headed for the same fate as Mahatma Gandhi. Just as Gandhi’s image turned him into a sarkari Mahatma, omnipresent and toothless, Bhagat Singh too could turn into a sarkari krantikari, a wrapping paper available to cover anything and everything. I shudder to think of Bhagat Singh’s image — historic or stylised — looking down at the everyday transactions and encounters of Punjab Police from the walls of every thana in the state.

Also read: Gwalior to Godse — Was Sardar Patel soft on Savarkar in Gandhi murder case, and if so, why

Reversing the appropriation

Bhagat Singh faces the ominous prospect of turning into an empty signifier, a symbol without any substance, a sign without a referent, just a basanti pagri that can be worn by anyone for anything, a figure that can be used to dislodge Gandhi, discredit Nehru and discard Tagore from our historical memory. Reversing this appropriation must be on the agenda of those who wish to reclaim a future for the Indian republic.

Such an effort would involve recovery of Bhagat Singh, the thinker-activist. Unlike most militant nationalists of his time, he was not a trigger-happy revolutionary. We need to remember the Bhagat Singh who read widely, thought deeply, wrote powerfully and acted fearlessly on his convictions. Specifically, we need to recall and recover three elements of his ideology: nationalism, socialism and secularism. We need to remember that Bhagat Singh’s nationalism was not a narrow doctrine of national superiority or chauvinism. His was a positive nationalism, born of a burning desire to unite all Indians in an anti-colonial struggle while willing to learn from anyone and everyone outside the country. This was related to his uncompromising secularism. He was an atheist who consistently fought against all forms of communalism. His remarks on the role of the media in fomenting communal hatred are worth remembering everyday in these times. Above all, revolution for him was linked to his ideology of socialism. He was among the first generation of Indian revolutionaries inspired by the Russian Revolution and the Marxist ideology. He was a socialist who wanted an India that could eliminate economic and social inequalities. The only way to resist Bhagat Singh’s appropriation is to invent a new image of this revolutionary by combining these three elements.

Such an effort would do well to remember that 23 March also happens to be the birthday of Rammanohar Lohia, someone who shared, in a different language, all these elements. We know that Lohia never celebrated his birthday and just marked it as the martyr’s day. If we forge a new image of Bhagat Singh, with or without basanti pagri, we can celebrate Lohia’s birthday together with Bhagat Singh’s martyrdom day.

Yogendra Yadav is among the founders of Jai Kisan Andolan and Swaraj India. He tweets @_YogendraYadav. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)