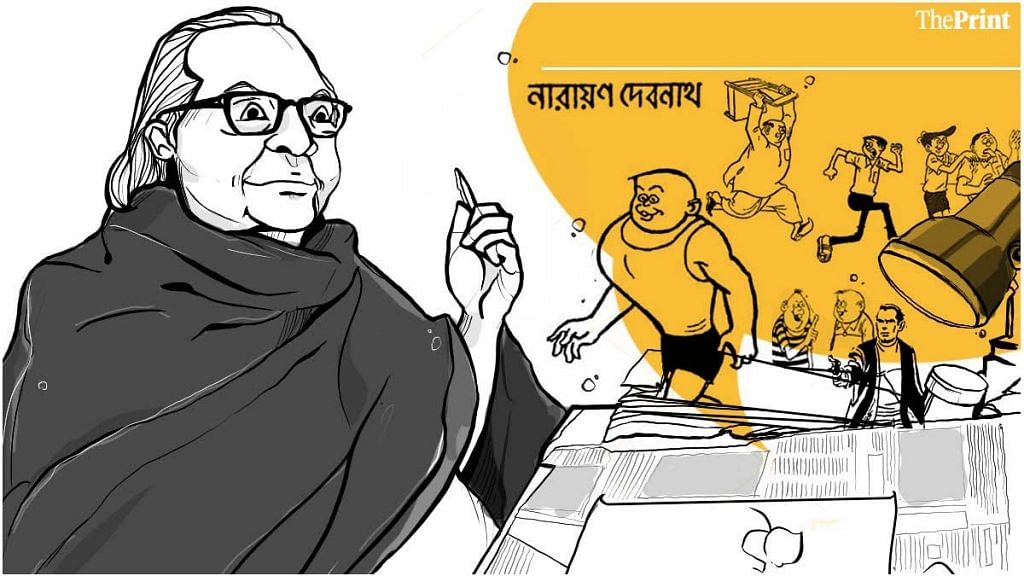

Genius and longevity do not always tread the same path, but when they do, the effect can be truly magical. Narayan Debnath, who passed away this week at the age of 97, was one such magician. He mesmerised generations of Bengalis with his words and illustrations, long after they had passed their formative years.

Debnath was both illustrator and writer for all his characters. His comic strip Handa Bhoda appeared for 55 straight years from 1962. Iconic character Bantul the Great, since making his first appearance in 1965, continued to enthral generations of Bengali children for the next 52 summers. Nonte Phonte was the third carriage in his creative engine. Started in 1969, it too ran uninterrupted until Debnath, then 92, himself brought all three to a reluctant stop in 2017.

At par with Asterix, Tintin, Phantom

Longevity in comic characters that attained iconic status has a certain history.

The original Asterix creators, Rene Goscinny and Albert Uderzo, published their work for over 18 years between 1959 and 1977, and Uderzo continued by himself from 1980 to 2005. Their total run was 43 years. Herge published the 24 four stories of Tintin over 47 years between 1929 and 1976. Lee Falk’s original Phantom was the longest-running comic strip of all time. It was first published in 1936 and Falk finished his last strip 63 years later in 1999 just before his death.

On this count alone, Debnath deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as this group of creative geniuses. But his impact went well beyond the number of active years in the genre.

The three strips, for which Narayan Debnath is best known, were originally meant for children. Handa Bhoda is about two friends who are forever trying to put one over the other, and Nonte Phonte is set in a boarding school, following the antics of two other friends. But it’s the third, Bantul the Great, that truly elevated Debnath from just a writer and illustrator of children’s comics, into a multi-generational doyen of Bengali literature.

Bantul came into my life when I was eight and given my first copy of Shuktara, the popular children’s magazine. The character, based on Bengali bodybuilder and former Mr Universe, Manohar Aich, was a child’s delight – a broad-chested superman with no pretensions to being one. Bantul had no blue and red cape, didn’t drive a Batmobile and had never fallen into a cauldron of magic potion. What made him special was his unassuming Obelix-like strength.

Also read: Tinkle and Amar Chitra Katha, the comics we grew up with that grew up with us

Cartoon goes political

Four years before I met him, a very interesting element had been added to Bantul’s character. It was 1971 and the Indian Army had just marched into East Pakistan to help Bengalis across the border found their own nation. The editor and publisher of Shuktara, in a subtle show of Bengali support, requested Debnath to give Bantul an element of invincibility. Bullets ricocheted off his body, he lifted tanks, uprooted buildings and cannon balls changed direction at his bidding. In that fateful year of conflict, Bantul the Bengali went from man to superman.

In Narayan Debnath’s simple world, there was no place for political statements. What you read was what you got – the triumph of good over evil through humorous situations enjoyed by children and adults alike. But after 1971, current events that affected the nation would often be used as a backdrop for subtle social messaging.

In 1999, Indian soldiers repealed Pakistani attacks in the Himalayan battlefields of Kargil along the Line of Control. Many lost their lives, families suffered. In one of Debnath’s strips at the time, a benevolent Bantul, caught but did not punish fraudsters raising money from unsuspecting people in the name of soldiers fighting in Kargil. Instead, he convinced them to hand over the money to the Army’s Family Welfare fund. A decade later, Bantul foiled a terrorist attack on a group of pilgrims on the Amarnath Yatra, capturing them and making it safe for people to continue their pilgrimage.

It was this ability to stay connected with contemporary issues and move with the times in the settings and messaging of his simple stories that made Debnath’s work so timeless.

Also read: Nandan, the children’s magazine that is more a collectors item for today’s generations

Don’t underestimate children

Six decades on, his characters remain immortal, and their creator, a household name among generations of Bengalis.

‘The trick is to never underestimate children,’ Debnath once said, explaining his success in staying relevant. ‘My characters were based on observations. I was talking about the boys of those times through these characters. The way they talked and dressed, everything was designed to make them more relevant to the young.’

Propped up on his hospital bed a few weeks ago, smiling at the camera recording his every move, Debnath sketched an image of Bantul the Great with bold strokes of his ever-obedient pen. It is only fitting that the last glimpse the world had of this genius at work would be of the artist and his most enduring character.

Anindya Dutta @Cric_Writer is a sports columnist and author of Wizards: The Story of Indian Spin Bowling, and Advantage India: The Story of Indian Tennis. Views are personal.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)