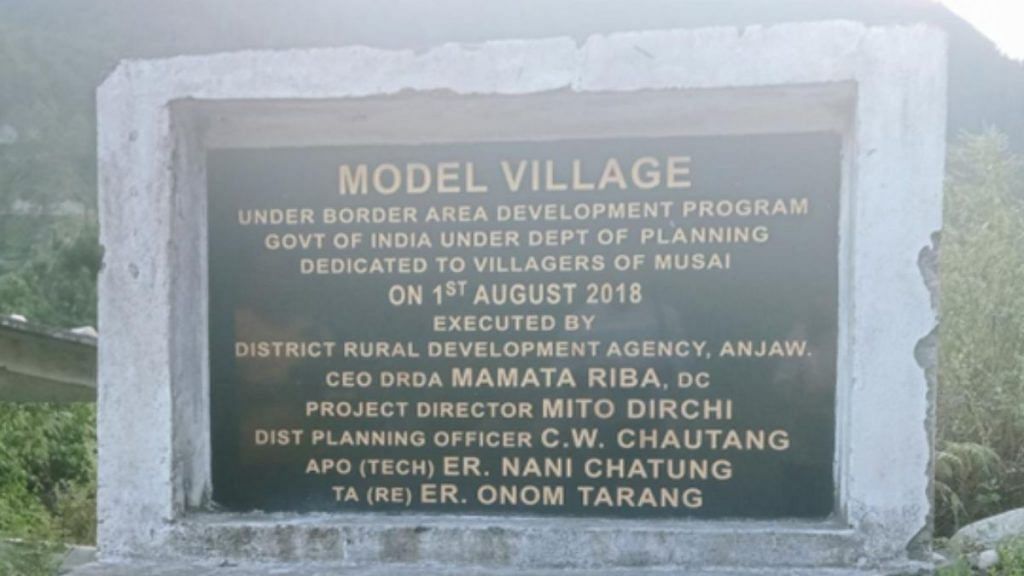

Eastern Army Commander Lt Gen Rana Pratap Kalita said last week that there was a proposal to develop 130 villages as model villages in Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim under the Vibrant Village Programme announced in Budget 2022-2023. “Work has started in two-three villages, Kaho [in eastern Arunachal Pradesh] to be specific,” Kalita had further said. A year earlier, in December 2021, Chief Minister Pema Khandu had launched a scheme to develop ‘model villages’ and selected three hamlets — Kaho, Musai, and Kibithoo. Interestingly, a commemorative stone at Musai—also known as Meshai—village says that it was converted into a Model Village on 1 August 2018. Obviously, something is amiss. Either the work was below par or not much seems to have been done.

The above reflects poorly on India’s approach to mirror the Chinese in developing its border infrastructure in general and vibrant/model villages in particular. According to Jayadeva Ranade, president of the Centre for China Analysis and former additional secretary of Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW), Beijing has completed construction work on 624 ‘xiaokang’ (well-off) border villages. China started this project in 2017 and completed it by the end of 2021. In fact, just opposite Arunachal’s Kaho village, 9 km across the Line of Actual Control, two such Chinese villages are visible on Google Maps.

Also read: India’s strategic paralysis with China must end. It is time to call out Xi’s border bluff

China’s border area development

Apart from security requirements, developing border infrastructure is the best way to assert physical claim over disputed areas, win over a restive population and show economic progress. Take Tibet and Xinjiang—border regions most prone to insurrection and the Achilles heel of an expansionist Chinese regime—where Beijing is constructing modern Xiaokang villages and road/railway networks. China is asserting its sovereignty by managing and developing its border areas and promoting tourism, and economic development in the process.

In 2015, three years after taking over as Chinese President, Xi Jinping spelt out his policy: “Governing border areas is the key for governing a country, and stabilising Tibet.” He reiterated this policy during the seventh meeting of the Tibet Work Forums held on 28-29 August 2020. This policy was formalised into a Land Border Law in October 2021 to consolidate China’s claims over territories that were occupied, disputed or vulnerable to insurgencies by non-Han populations.

In January 2021, the Indian media sensationalised the discovery of a Xiaokang village on the Tsari Chu River in the upper Subansiri district, an area usurped by China in 1959. But when M. Taylor Fravel, an eminent China scholar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explained that the village was part of a $4.6 billion Chinese project to revitalise its border areas, it was nothing short of an eye-opener for India.

As per Ranade, the Xiaokang villages are intended to create a buffer along the border, inhabited by people loyal to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the nation. These modern villages are easy to monitor via Wi-Fi-enabled devices and will act as military garrisons for operations in areas where the Tibetan population can potentially turn hostile.

China is also enhancing its border roads and rail infrastructure. It is constructing a new highway, G695, about 20-50 km away from the LAC. Unlike the existing G219, which is three to four times this distance, the G695 runs close to the Indian border. It will likely be connected to the LAC and G219 through existing or new lateral roads. Next comes China’s strategic rail line from Sichuan to Tibet, which is divided into three sections and connects key Chinese provinces to Tibetan ones. Work on one of these sections, the Lhasa–Nyingchi railway line, has already been completed. China is also constructing a railway line to Nepal.

Also read: Many factors led to Army giving up in 1962. But psychological collapse played a big role

Border development needs holistic approach

Since 2014, the Indian government’s primary focus while developing its northern borders has been on military infrastructure such as roads, defence installations and habitat for soldiers. It has also initiated several strategic rail projects to connect the country’s northern borders. However, the civic and economic development of border areas has been neglected. There is little or no military-civil fusion, while inner-line permits are still in vogue and deter tourism. Suffice it to say that the little civic and economic development that has taken place is because of military infrastructure projects.

India has had a centrally funded Border Area Development Programme (BADP) since 1986-87 for the security and well-being of its border population. However, development has been marred by inadequate budget allotment and tardy execution. For one, BADP funds were halved from Rs 1,100 crore in the financial year 2017-18 to Rs 565.72 crore in FY 2022-23— and further slashed to a dismal Rs 221.61 crore that year. As per the government’s reply to a starred question in Parliament, the actual funds allocated from FY 2018-19 to FY 2021-22 were Rs 770 cr, Rs 824 cr, Rs 63.97 cr and Rs 190.98 cr.

The funds allocated to the northern border areas of Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh for FY 2020-21 were Rs 162 cr, Rs 30 cr, Rs 32 cr and Rs 31 cr. Now, compare this to the $4.6 billion, or Rs 3.76 lakh crore, allotted to construct 624 Xiaokang villages in three years. India likely announced Vibrant Villages Programme in response to these developments.

“We have decided that we will develop the villages on India’s borders. For the same, we are moving forward with a holistic approach. Such villages will have all facilities—electricity, water and others—and a special provision has been made in the budget,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi while emphasising the importance of this scheme last year.

But there was no news of VVP after last year’s budget. Nothing on record shows that specific funds were allocated for this initiative or that convergence with BADP and state government programmes indeed occurred. The project went off the radar until it was brought back into focus by the Eastern Army Commander on 27 January. “We are trying to evolve a methodology of some sort of a single window clearance for any infrastructure coming up within 100 km from the LAC,” Lt Gen Kalita had said. The VVP, thus, is yet to take off, even a year after its launch.

India must adopt a holistic approach and construct 500-600 Vibrant Villages along the northern borders to match China. China has spent Rs 60 crore per village. Given our sparse population and lower construction cost, we can accomplish this with half of China’s budget. Thus, the entire project will need a budget of Rs 15,000- 18,000 crore. There is a need for civil-military and Centre-state fusion. Our current administration is incapable of executing a project of this nature. I can only think of the Army or the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) as the lead agencies for developing the 10-20 km belt along the borders. The project must be centrally funded. Given the ample scope for tourism, public-private participation could be encouraged. Corporate houses should be motivated to adopt such villages. Each Vibrant Village must showcase local culture and be made economically self-reliant.

On 12 July 2018, then Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh had announced the development of 61 model villages in border areas with the same facilities as now spelt out for Vibrant Villages. One can only hope that Vibrant Village Programme gets the desired impetus and funding and that the Army ensures that Kaho becomes India’s first Vibrant Village.

Lt Gen H S Panag PVSM, AVSM (R), served in the Indian Army for 40 years. He was GOC in C Northern Command and Central Command. Post-retirement, he was Member of Armed Forces Tribunal. He tweets @rwac48. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)