Data shows the Indian voters’ habitual anti-incumbency sentiment has tempered.

A consensus seems to have emerged among the political observers that the Bharatiya Janata Party may retain Chhattisgarh, the Congress may win Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh (MP) remains closely contested with no clear winner in sight.

There are at least four problems with such formulations that reduce the process of electioneering in democracies to mere outcomes. Such formulations consider Indian voters as mere pawns in coalition games, competitive populism and leadership contests. It assumes that Indian voters are blindly tied to their ethnic identities and rarely reward or punish their incumbents based on governance indicators such as bijli, sadak and paani.

First, this consensus treats each of these elections in isolation. The polling in Chhattisgarh would be over today, Madhya Pradesh votes on 28 November, and Rajasthan on 7 December. While the counting of votes for all the three states would take place on 11 December, the party cadres on the ground will start formulating their expectations about the results after polling ends in their respective states.

Also read: State elections are bad news for BJP and not good news for Congress either

If the sentiment about one party leading the polls in both Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh gains ground, then by the time campaigning in Rajasthan enters the last lap, that party’s cadre would be relatively more enthused while campaigning. Simultaneously, the other party’s cadre could get demoralised. This may also very well lead to a situation of over-confidence for one and a do-or-die battle for the other, but not considering the domino effect would amount to missing an important aspect of phased elections.

Second, there is no clear explanation behind this consensus and one hears a complicated mix of arguments to retrofit this narrative. For Rajasthan, you get a catchy slogan as the answer – “Modi tujhse bair nahi Vasundhara teri khair nahi” (we don’t have a problem with Modi, but Vasundhara has had it). If you ask why, there will be silence. About Chhattisgarh, the argument relies on Ajit Jogi’s new outfit Janata Congress and its alliance with the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). We are told that the alliance’s support base among the Dalits and tribals is damaging the Congress party’s prospect far more than the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). As these two factors are not present in Madhya Pradesh – no strong third player and an incumbent chief minister who is still popular – the conclusion is that it is a closely contested election.

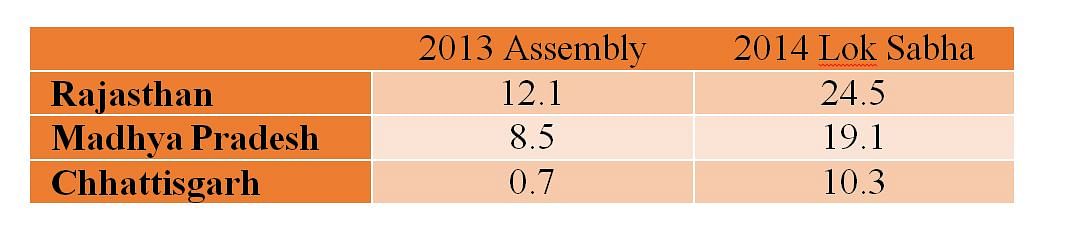

Third, the present consensus in Lutyens’ Delhi disregards the basic arithmetic of electioneering. To defeat an incumbent, the opposition needs to swing votes away from the incumbent. The data presented in Table 1 suggests that contrary to Lutyens’ Delhi’s belief, it should be hardest for the Congress to defeat the BJP in Rajasthan and easiest in Chhattisgarh as the gap between the two parties is largest in Rajasthan. The gap in vote share between the BJP and Congress was more than 12 percentage points during the 2013 assembly election, which doubled during the Lok Sabha polls. Given this huge gap between the two parties, if the observers believe that the Congress has an edge in Rajasthan then there must be a strong disenchantment with Vasundhara Raje as well as with the BJP. Why would only Raje bear the burnt and not Modi in 2019?

Table 1: BJP’s vote share lead over Congress

Source: Authors’ calculation from ECI data

Fourth, voters are largely missing from this narrative. Even when voters are given a place in the story, it is merely through caste alignments. Since Gujarat assembly elections last year, a new narrative of an urban-rural division has come into prominence. Some have suggested that this divide may well get reflected in this round of elections, especially in Madhya Pradesh. It would be important to note that there has always been an urban-rural division in Indian politics with the Congress (and regional parties) drawing more votes in rural areas and the BJP’s support base being stronger in urban areas. Moreover, Lokniti’s pre-poll surveys in all the three states show that despite some discontent, a sizeable proportion of voters in rural areas (even farmers) may vote for the BJP. In that sense, it is unlikely that urban-rural differences are going to become sharper than what has been previously observed.

Also read: The tribals of MP have the power to swing elections. Not much else

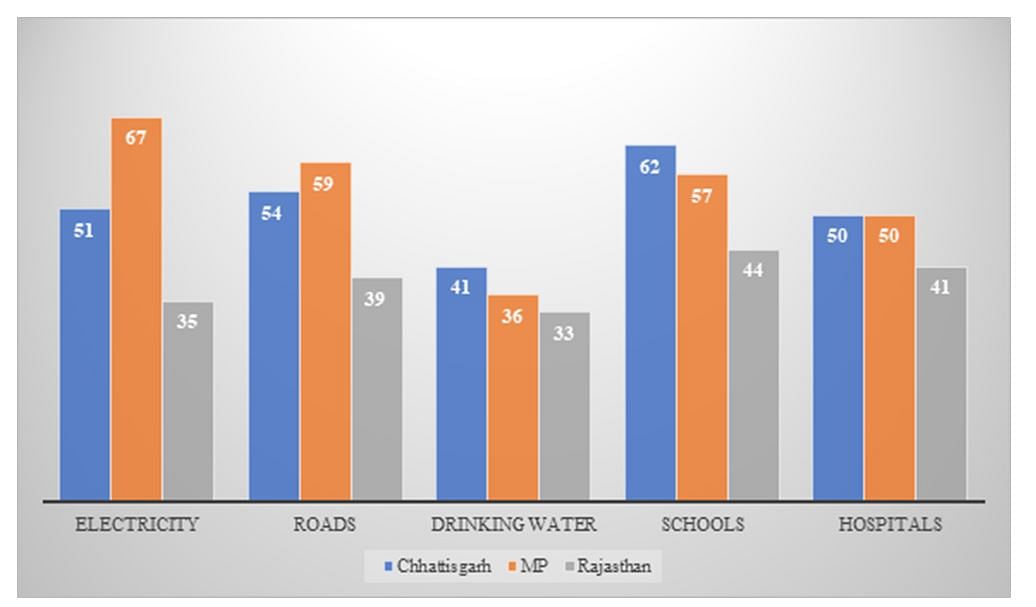

Basic governance issues, on the other hand, cut across such divides and we can see its resonance in all three states. The data presented in Figure 1 shows that a large majority of voters in Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh perceive that there has been an improvement in the availability of electricity, roads, drinking water, health and education in the past five years. The record of Rajasthan government is poorest on all the five indicators. It also indicates why the incumbents in Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh have a fairly better chance of coming back as compared to the incumbent in Rajasthan.

Figure 1: Voters’ perception of improvement in development indicators

Source: Lokniti-CSDS, pre-poll 2018.

Does this mean that Indian voters have shed all their preoccupation with ethnic ties and patronage networks, and vote only on the basis of government’s performance? We do know that voters in India are more likely to hold state governments accountable for governance indicators and welfare schemes. I would be, however, cautious in reading too much into public perception about governance indicators and its correlation with voter choice. We do not know whether the evaluation of an incumbent’s performance recorded in election surveys is an independent assessment of the voters or simply a rationalisation of the way they are likely to vote.

In other words, as Yogendra Yadav and Suhas Palshilar wrote after the 2009 elections, “do people vote the party whose government they liked, or do they say they like the government whose party they have voted for?” More importantly, one must recognise the merit in Pratap Bhanu Mehta’s sage advice at the time of 2004 elections that to describe Indian voters as “maturing voter[s]” or giving them “as bland a title as ‘the governance voter’ is to miss the tumult of Indian politics”.

Also read: Vasundhara Raje’s struggle to get Muslim loyalist a BJP ticket holds a message for 2019

However, elections in democracies are sites to hold representatives accountable for their actions and inaction. This dictum lies not only at the heart of democratic theory but also of democratic praxis, and the evidence from elections over the past decade indicates a clear shift in voting patterns in India. The habitual anti-incumbency has been tempered. There is a decline in voting patterns purely based on patronage or ethnic considerations.

Thus, to reduce Indian voters as mere emotive beneficiaries of election spoils or reactionaries on identity issues is to miss how their aspirations are playing a larger role than ever in determining election outcomes. It’s time we recognise them as active participants in the functioning of Indian democracy, else we will keep getting surprised after the election results.

The author is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of California at Berkeley, US.

the real issue is vote shares in the state elections – and a resurgent Congress – and a corrupt BJP

One would be most surprised if Rani teri khair nahin is not punched onto the EVMs. In both MP and Chhatisgarh, after fifteen years, serious anti incumbency has built up, although both CMs are far superior to many of their colleagues in other states like Haryana and UP. Change would be expected, normal. The Congress has potential CMs in MP, not really in Chhatisgarh. Ajit Jogi and Mayawati have clearly been propped up, a strategy that might pay off.

Any one using the word Lutyens’ in India is irrelevant and not an Indian journalist. Just skip and do not waste time reading the crap.