Those who believed that the unanimous, five-judge Supreme Court judgment on the Ayodhya Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute would also bring closure to other divisive temple-mosque controversies in India were rudely shaken by a district court in Varanasi. The ghosts of the subcontinent’s contentious medieval history aren’t buried so soon.

The court, headed by judge Ashutosh Tiwari, allowed a civil suit seeking an Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) study of the Gyanvapi Mosque site to determine if it had been “superimposed” after demolishing the Kashi Vishwanath Temple that might have originally stood there. Immediately, this looked like a sequel to the Ayodhya story. This time, launched judicially.

To get disclosures out of the way, I’ve been among those optimists who thought Ayodhya was the last such dispute. Surely, it wasn’t settled to everybody’s full satisfaction, but the Supreme Court had made a case unanimously and all sides seemed to respect it. How does one interpret this latest turn now?

If you asked me to write, say, an editorial comment on it, I could simply reproduce a passage from that particularly well-written judgment.

The five Supreme Court judges took note of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act of 1991 that laid down that all shrines will be preserved as inherited by independent India on 15 August 1947. The law made an exception for Ayodhya as it was already an ongoing dispute. Nothing else was deserving of an exception, nor was it legally or constitutionally possible, the judges wrote.

Also read: Modi’s Hindutva 2.0 written on Varanasi walls: Temple restoration, not mosque demolition

Here is how our editorial on this would go if we were to simply plagiarise passages from the Supreme Court order. After references to the Places of Worship Act came the operative paragraphs, where the court laid down the law for the future. “Non-retrogression is a foundational feature of the fundamental principles of the Constitution, of which secularism is one,” the judges wrote.

“Non-retrogression is an essential feature of our secular values,” stated the judges, adding that our “Constitution speaks to our history and future of our nation…while we should be cognisant of the history, we need to confront it and move on”. The judges elaborated in that landmark order that independence, gained on 15 August 1947, was a great moment for healing the wounds.

The judges then went back to pick up the thread from the Places of Worship Act to emphasise the fact that “Parliament has mandated in no uncertain terms that history and its wrongs will not be used to oppress the present or the future”. We can summarise the essence of that judgment in three points.

1. All religious places must be protected as independent India inherited them on 15 August 1947 with the exception of the dispute over Ayodhya.

2. Even if a future Parliament in its wisdom decided to repeal or amend this law, this judgment would come in the way as the judges had placed the spirit of “non-retrogression” at the heart of our secular Constitution, as part of its basic features. A foundational feature of fundamental principles of the Constitution. Which, we know, can’t be amended.

3. It was a call to the nation, the government, political parties and religious groups to move on from the past.

It was on the assurance of these readings that many, including this writer, believed that the controversies over all other similar disputes were now buried and cremated. Two familiar slogans across decades of the Ayodhya agitation were, “yeh toh kewal jhaanki hai, Kashi-Mathura baaki hai”, and then, “teen nahin hain, teen hazaar”.

The first harked to the sites of the temples and mosques standing next to each other in Mathura, Lord Krishna’s birthplace, and Varanasi. The second said there was much more to come and that the campaign will be taken to any Muslim place of worship that “had been built by demolishing a temple”. That number, “conservatively”, was three thousand.

The Supreme Court judgment expected to provide closure to all these divisive ideas. It was also the language and spirit of the order. It made those like us who had lived through the divisive, violent nightmare of Ayodhya over three decades imagine that there will be no repeats. This Varanasi court order, unfortunately and with a questionable application of law, places a question mark on that optimism now. It is evident that judge Tiwari has either not read the Supreme Court order, or makes a radically different interpretation of its meaning.

Also read: Babri ruling is BJP’s golden goose. Mathura, Kashi signal to erase India’s Islamic history

Any reasonable judge in a higher court, especially a high court, would dismiss this Varanasi order. But some questions arise.

One, how did this spark suddenly light up? There was a suit filed over Mathura as well recently. So, are these actions taken in concert with a common intention? If so, does it have the blessings of the people at the top of the VHP-RSS and BJP? And, finally, if that is indeed the case, and if their intention is not to respect the essential spirit of the Supreme Court judgment, will they stop even if a higher court throws out this order?

There is nothing to stop it from following the course of the Ayodhya movement. And now that it’s been choreographed already, the next one might not take two centuries. In this case, majority can rule, and so what if it causes bloodshed and disruption for another decade or more? What price is too much to pay for “righting the wrongs of history”? This, a resumption of 16th and 17th century wars in 21st century India will be an invitation to disaster. It will hold the future of our coming generations to ransom.

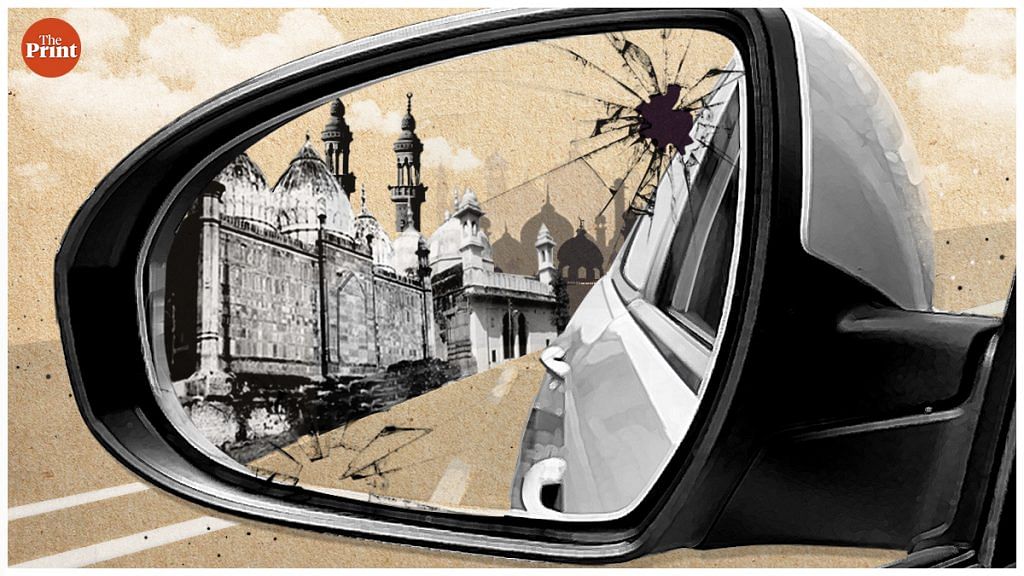

History is never to be taken lightly. That is why it is taught so widely and the reason it is so politicised. But, basing decisions impacting your future on your understanding of history is like driving on an expressway by looking not across the windscreen, but at the rear-view mirror. You are bound to hit something nasty soon enough, hurting yourself and others.

One of the most quoted passages from columnist Tom Friedman’s 2005 book The World is Flat is about which countries, companies and organisations are likely to do well, given the relative balance of their dreams and memories. “I am glad you were great in the 14th century, but that was then and this is now,” he wrote. “In societies that have more memories than dreams, too many people are spending too much time looking backward. They see dignity and self-worth not by mining the present but chewing on the past…and that is usually not a real past but an imagined and adorned past…they cling to it, rather than imagining a better future and acting on that.”

The Supreme Court order on Ayodhya had cued us precisely in this direction, the future. The Varanasi court, and celebratory responses from the partisans, are tempting us to make an about-turn. The choice is ours.

Also read: Why Babri masjid demolition verdict is unlikely to end all temple-mosque disputes