New Delhi: Muhammad Arif lives in Mandhka Majre Aurangabad, a village nestled in the Gauriganj tehsil of Amethi. Not just with his family, but with a Sarus crane.

About a year ago, the bird found itself badly injured in the fields in which Arif was working. Its right leg was broken and bent at an angle. Despite having no prior knowledge, Arif managed to repair the leg. Later, he built a rehabilitation ground outside his house for the bird to rest.

The mighty creature, the world’s tallest flying bird, which grows up to a height of 156 cm, was in no position to retaliate, to nip at its caregiver or his family. “This is a jungle bird. I picked him up, he couldn’t bite. So I was able to take care of him,” Arif told ThePrint.

The Sarus crane is native to northern India and can be found in the paddy fields of Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, West Bengal, Gujarat, and Assam. There are currently between 15 and 20,000 of these birds in India.

Arif lives with his family — his mother, wife, and two children. When they saw the Sarus, they were aghast, afraid that it would attack them.

Once it was able to fly, Arif set it free.

“But he never left. He always stays with me. While I’m eating, while I’m bathing –– he is always there,” said Arif.

This was far from what he had expected. “I thought it would go back to its friends, to where it came from.” Instead, dependence morphed into attachment and only increased in intensity. Arif is not sure, but the villagers estimate that the bird might be 2.5 to 3 years old.

Sarus cranes are primarily omnivores –– consuming insects, small fish, and aquatic plants — given that they are birds of the wetlands. This is not the case with this particular Sarus, who Arif says, prefers to eat whatever he does. Dal and roti have become standard fare for him.

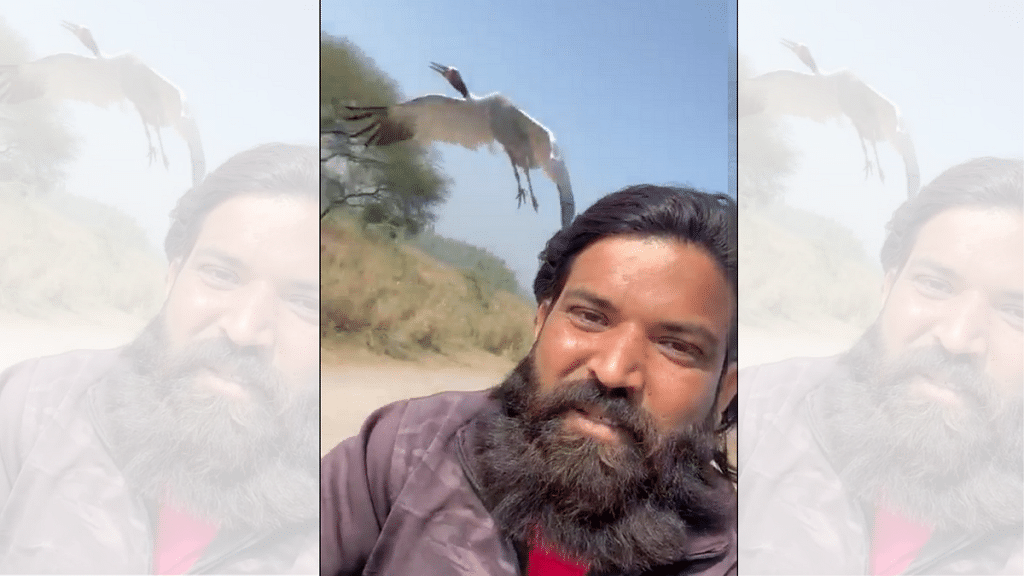

The relationship is such that when Arif travels, the bird follows. In a video, Arif can be seen zooming on his motorbike while the bird flaps its wings just a few feet behind –– never drifting too far from its human companion.

“It travels up to 30-40 kilometres with me,” he said. “I make sure not to go too far with it though, as I know it [the sarus] gets tired.”

The bird is attached to the point that if Arif leaves for a few hours, it will wait and be excited upon his return –– happily playing with him.

“His friends come on occasion to take him back. But he never goes. He goes to the verandah. He plays with them sometimes. But in the evening, they return home and he comes back to me,” said Arif.

This playful, loving relationship is unique to Arif. His family members don’t ‘play’ with the red-necked, long-legged, and sharp-beaked animal, whose grey plumage extends to an astounding 242 centimetres.

Part of family

The Sarus is listed under Schedule 4 of the Wildlife (Protection) Act and is classified as a vulnerable species. In India, their highest population is found in Uttar Pradesh. TK Roy, a conservationist who works with Wetlands International South Asia, says that typically, wildlife authorities need to be informed and that the distinction between wild and domestic needs to be sacrosanct. Wild animals cannot be pets. However, the Sarus who lives with Arif is not held captive.

“After proper rehabilitation and recovery, they need to be released into the wild,” he said, adding that animals do not forget the person that takes care of them. “It [the animal] will not forget. This happens with every species.”

He attributes the cause behind such cases to human encroachment, as more animal habitats are converted into agricultural land and wetlands are drained.

Sarus cranes are usually left with no choice but to forage in fields, ingesting pesticides and consequently being poisoned.

Conservation efforts for the Sarus crane, however, have yielded results. The bird’s population has nearly doubled in the wetlands of Matar Taluka, Kheda, as a result of a number of projects carried out in collaboration with locals and the district forest department, reported the Indian Express.

Farmers from surrounding areas coexist with their wild neighbours, even leaving their fields undisturbed for close to two months during the Sarus breeding season, which takes place from June to September.

As for Mandhka Majre Aurangabad’s resident Sarus, he too is free to do as he pleases. “He is part of my family now,” believes Arif.

(Edited by Tarannum Khan)

Also read: Climate fiction is growing, but it’s waiting for a Chetan Bhagat