Srinagar: “Aaj kya khaaoge bataao, main banayega (what will you guys eat today? I will cook),” says Sajad Ahmad, 50, to his workers before he leaves for the market to buy vegetables. When he finally steps out of his shop at the Zaina Kadal area in Srinagar, he locks the door behind him.

The idea is to mislead people into believing the premises are empty.

Zaina Kadal is located a few kilometres from the Eidgah area, where a golgappa seller was shot point blank by terrorists Saturday. Arvind Kumar Sah, 30, of Bihar’s Banka district, is one of 11 civilians left dead by a wave of terrorist violence in Kashmir this month.

The dead include a popular pharmacist — a Kashmiri Pandit who refused to leave during the peak militancy days, two teachers (a Hindu and a Kashmiri Pandit), and three Muslims. The remaining five were all migrant workers — men from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh who had arrived in Kashmir to eke out a living.

The Resistance Front, a Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) offshoot, has taken responsibility for some of the murders.

The spate of killings has triggered a mass flight of migrant workers from Kashmir, which offered them the promise of up to triple the wages they could earn at home as well as assured work for longer periods.

Aware of the fear, many local residents like Sajad Ahmad are doing their bit to protect the migrant workers in their employ — to make them feel at home as much as possible.

At this difficult time, the migrant workers say these efforts by Kashmiris, whose hospitality they swear by, is helping them stay on.

Shyam Sunder Yadav, a 32-year-old mason who works in Lal Bazaar, said he was working in the same area as Virendra Paswan, the first migrant worker killed, when he was shot dead. However, he added, he is “getting the courage to stay back and complete the work because of local residents”.

“We are 10 of us from Motihari district of Bihar, and have been coming to the Valley together,” he said.

“Kashmiris have always treated us very nicely but now they are being very helpful and more protective for us, even making meals for us and dropping us home after work. I stay in the Hawal area with nine others from Bihar. Each day, we are being picked up and dropped either by my owner or the local residents living next to us.

“If they cannot arrange a car or an auto, 4-5 of them walk with us to our work location,” he added. “Everybody knows me by my name, so now I feel confident somehow.”

Also Read: Many Pandits move out, Sikhs worried as Kashmir minorities fear ‘return of 1990’ after killings

‘Kashmiris love my chaat’

The migrant workers in Kashmir say the Valley is an enticing job location for them.

According to them, skilled labourers like carpenters, painters and masons get up to Rs 500-600/day in Kashmir, against Rs 250-300 in states like UP, Bihar and West Bengal. These states are believed to send out large numbers of migrant workers across the country. Government estimates suggest the three states accounted for 50 per cent of the migrant workers who returned home from cities amid the Covid lockdown last year.

The likes of chaat and golgappa sellers earn Rs 400-500/day in the Valley, compared to Rs 100-150 in Bihar and UP, the workers add.

The migrant workers also say they find assured work for at least 20-25 days/month in Kashmir, while there is no such guarantee in their home states.

Then there is the hospitality of Kashmir, many migrant workers told ThePrint. In Bihar and UP, they said, labourers have to take care of their meals and accommodation by themselves. In Kashmir, owners or contractors pay for the food and accommodation.

“I used to work as a farmer in UP, and you know the condition of farmers in our country. Wages were so low that they would not even fill our stomachs,” said Sudama Prasad, a 62-year-old from Hardoi district in Uttar Pradesh, who runs a chaat shop at the TRC bus station in the heart of Srinagar.

“So I decided to come back to Kashmir after Covid. Here, I earn at least Rs 15,000-20,000 a month, which is sufficient for my family. Plus, the local residents are really helping us,” he added.

It’s not that the situation in the Valley is not affecting them. But while the migrant workers choosing to stay back cite financial compulsions, they also say they have formed a bond with the people.

Yadav said he had been coming to Kashmir “for the last 12 years and built many buildings including police stations, government buildings, but I have never seen this kind of a situation ever before”.

“Even during peak militancy, migrants were not targeted like this. I am very scared but have to complete the work, otherwise what will I take back home during Diwali?” he added. “I am the only earning member in my family of 6.”

Prasad said he has been “selling chaat in Srinagar for more than a decade now” and “Kashmiris love my chaat”.

“I have seen very bad times in Kashmir, but I thought after so many claims the government has made, things would have changed. But it’s worse now,” he added. “But somewhere we are all bound by our duty and responsibilities. If I go back, my wife and physically challenged kid are going to starve.”

Prasad said he sees many migrant workers leaving for home every day in buses, but he does not want to go back, detailing the steps Kashmiris are taking to protect him.

“My neighbours’ sons pick me up and drop me every day. At the bus station, all drivers take extra care of me. They are doing as much as they can on humanitarian grounds, now the rest is up to God,” he added.

Sajid Ahmad runs an embroidery warehouse in the Valley that employs 20-25 migrant workers, most of them from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. In light of the killings this month, Ahmad’s employees said he has been staying with his workers to make them feel safe. Ahmad, they added, has also been fetching vegetables and other necessary items for them.

Speaking to ThePrint, Ahmad said protecting his workers was a responsibility he had to fulfil.

“Biggest masla (problem) for us Kashmiris right now is the protection of our migrant workers. These people have built our houses, our warehouses, our offices, the clothes we sell, how can we leave them when they need us the most?” he added.

“I have told all my workers to stay inside the warehouse till the situation gets better. I have put heaters in their rooms. I bring them vegetables, soaps, medicines, whatever they need, on a daily basis so that they don’t have to go out. I lock the door from outside so that it looks like nobody’s inside,” he said.

Ahmad added that his wife has a knee problem and can barely walk in the winter “but I have told her that I am not going to come home”. “I will stay with my workers till the time they need me to. I am not leaving them alone. I will take a bullet for my people, if need be,” he said.

‘We have their backs’

Sameer Wani, a contractor who works in Eidgah, said local residents “have the back of migrant workers”.

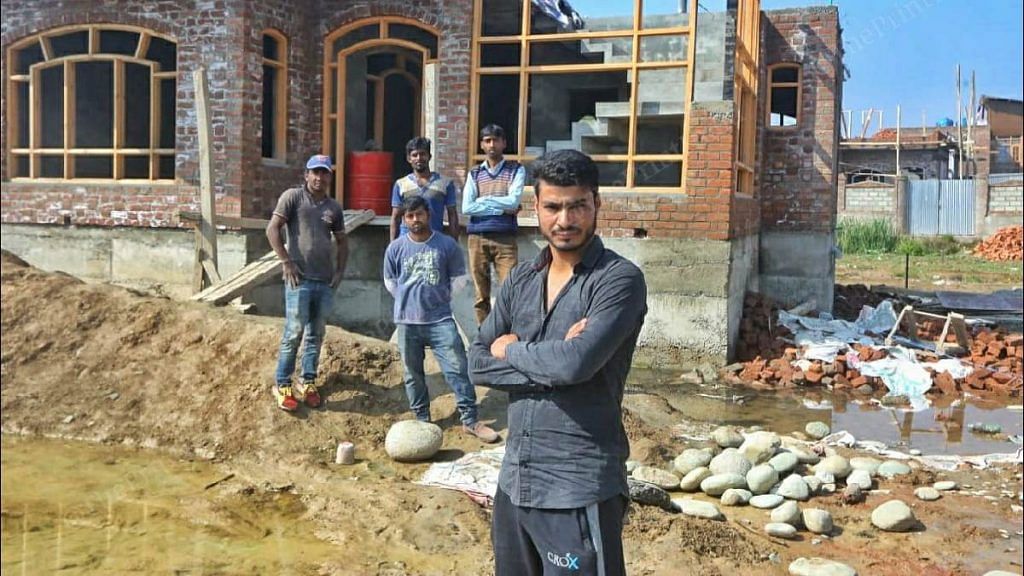

“I bring at least 80-100 labourers every year to Kashmir from different states. They prefer to complete their work and leave before the start of Kashmir’s brutal winter but, this year, some have gone back early because there is fear in the atmosphere,” he told ThePrint.

“But we have the backs of those who have stayed back. I have been personally checking up on each of my workers every day. I, along with 5-6 of my friends, go and spend time with the workers at their rented accommodations so that they also feel secure and at home.”

Assurance of safety, Wani said, is very important for them right now.

“We are also suffering because of the militancy. We want to give out a loud and clear message to the militants that their actions are causing harm to nobody else but Kashmiris,” he added. “No outsider would ever come to Kashmir if this continues and we do not want that. Local residents will suffer the biggest loss. So, we are doing everything in our capacity to protect non-locals, especially migrants.”

Javeed Bhat, president of the Industrial Association of North Kashmir, said it is their “moral duty and responsibility to safeguard our migrants, be they from any religion”.

“Sopore has Asia’s second largest apple mandi and we have at least 8,000-10,000 migrants, which include farmers, truck drivers coming in every day. We also have hundreds of migrants, mostly from Bihar and UP, working in different industries, including furniture, garments, steel bridges, mats, embroidery, and nobody is leaving the Valley despite the threats because we are with them,” he added.

“We have made quarters inside our industries where they are staying with their families. From food to soap to books for kids, everything is being provided to them free of cost inside their rooms.

“At least 15 members of the industrial association go every day to check on migrants personally and we have even given them private security from our own money. Gates are always closed and nobody can enter without showing proper documents. Migrants are our families and we are doing all we can to protect our families.”

Ahmad said they will do all it takes to protect their workers, adding that he has been haunted by guilt since the 1990s.

“We are living with guilt and blame for not providing enough support to the Pandits during their killings by militants in the 1990s,” he added. “We cannot take another set of blame on us for the cowardly actions of the militants. This time, we’re not letting anyone die on our watch. We will do whatever we can to provide security.”

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: Lashkar offshoot circulated ‘how to target non-locals’ document month before Kashmir killings