New Delhi: On 18 November, the Allahabad High Court urged the Centre to implement a Uniform Civil Code, terming it as a “necessity”.

“A common civil code will help the cause of national integration by removing disparate loyalties to laws which have conflicting ideologies,” the court observed.

“No community is likely to bell the cat by making gratuitous concessions on this issue. It is the state which is charged with the duty of securing a uniform civil code for the citizens of the country and, unquestionably, it has the legislative competence to do so,” it added.

On the occasion of Constitution Day on 26 November, it would be pertinent to look at the debate in the Constituent Assembly on the issue of the Uniform Civil Code.

Also read: Uniform Civil Code ought not to remain a mere hope, India becoming homogenous, says Delhi HC

At the Constituent Assembly

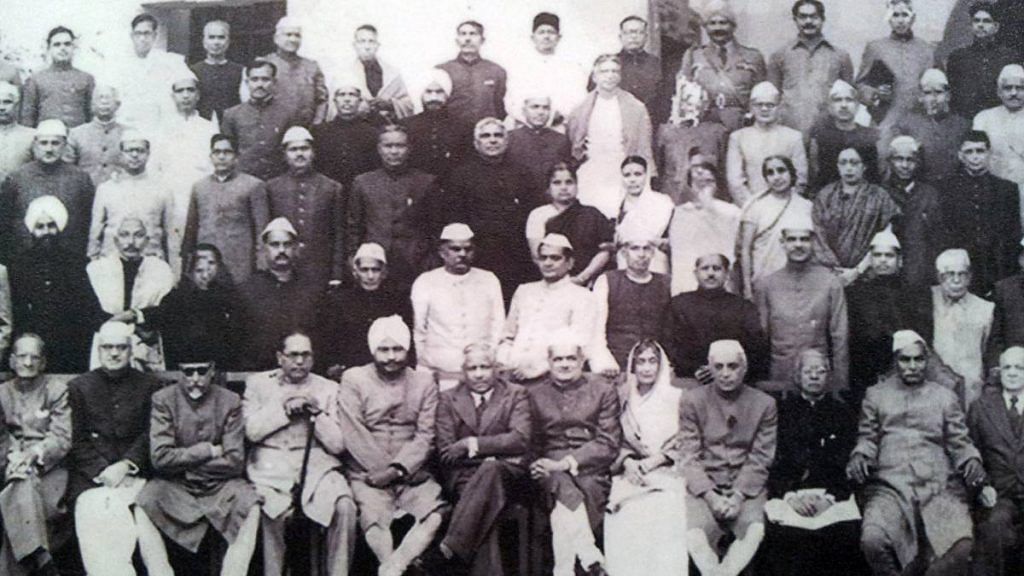

The issue was discussed at length at the Constituent Assembly on 23 November 1948.

First, the Muslim members spoke and moved several amendments to Article 35, which had provisions related to a Uniform Civil Code. Muhammad Ismail, Naziruddin Ahmad, Mahboob Ali Baig Sahib Bahadur, Hussain Imam were among those who moved these amendments.

Naziruddin Ahmad moved the amendment, saying, “That to Article 35, the following proviso be added, namely: ‘Provided that the personal law of any community which has been guaranteed by the statute shall not be changed except with the previous approval of the community, ascertained in such manner as the Union Legislature may determine by law’.”

“In moving this,” added Ahmad, “I do not wish to confine my remarks to the inconvenience felt by the Muslim community alone. I would put it on a much broader ground. In fact, each community…has certain religious laws, certain civil laws inseparably connected with religious beliefs and practices. I believe that in framing a uniform draft code these religious laws or semi-religious laws should be kept out of its way.”

Moving another amendment, Muhammad Ismail, the Muslim member from Madras, said, “I move that the following proviso be added to Article 35: ‘Provided that any group, section or community of people shall not be obliged to give up its own personal law in case it has such a law’.”

“The right of a group or a community of people to follow and adhere to its own personal law is among the fundamental rights and this provision should be made amongst the statutory and justiciable fundamental rights,” Ismail said.

“The right to follow personal law is part of the way of life of those people who are following such laws; it is part of their religion and culture. If anything is done affecting the personal laws, it will be tantamount to interference with the way of life of people who have been observing these laws for generations. This secular state which we are trying to create should not do anything to interfere with the way of life and religion of the people,” he added.

The counter-argument

These arguments were countered by B.R. Ambedkar, K.M. Munshi and Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar.

Strongly favouring a Uniform Civil Code, Ambedkar said, “I think most of my friends who have spoken on this amendment have quite forgotten that up to 1935 the North West Frontier Province was not subject to the Sharia. It followed the Hindu Law in the matter of succession and in other matters, so much so that it was in 1939 that the Central Legislature had to come… And abrogate the application of Hindu Law to Muslims of the North West Frontier Province and to apply the Sharia to them.”

He further added, “I quite realise their feelings in the matter, but I think they have read rather too much into Article 35, which merely proposes that the state shall endeavour to secure a civil code for the citizens of the country.”

Munshi, meanwhile, said: “Look at the disadvantages that you will perpetuate if there is no Civil Code. Take for instance the Hindus. We have the law of Mayukha applying in some parts of India, we have Mithakshara in others, and we have the Dayabagha law in Bengal. In this way, even the Hindus themselves have separate laws and most of our provinces and states have started making separate Hindu law for themselves. Are we going to permit this piecemeal legislation on the ground that it affects the personal law of the country? It is therefore not merely a question for minorities, but also affects the majority.”

“This attitude perpetuated under the British rule that personal law is part of religion has been fostered by British courts. We must, therefore, outgrow it,” exhorted Munshi.

“If I may just remind the honourable member who spoke last of a particular incident from Fereshta, which comes to my mind, Allauddin Khilji made several changes to the Sharia… The Kazi of Delhi objected to some of his reforms, and his reply was, ‘I am an ignorant man and I am ruling this country in its best interests. I am sure, looking at my ignorance and my good intentions, the Almighty will forgive me, when he finds that I have not acted according to the Sharia’. If Allauddin could not, much less can a modern government accept the proposition that religious rights cover personal law or several other matters which we have been unfortunately trained to consider as part of our religion.”

Speaking in favour of a Uniform Civil Code and opposing the amendments proposed by the Muslim members, Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar said, “The second objection was that religion was in danger, that communities cannot live in amity if there is to be a uniform civil code. The article actually aims at amity. It does not destroy amity. The idea is that differential systems of inheritance and other matters are some of the factors which contribute to the differences among the different peoples of India. What it aims at is to try to arrive at a common measure of agreement in regard to these matters.”

At the end of the arguments, the members voted overwhelmingly in favour of a Uniform Civil Code being part of the Constitution.

The writer is a research director at RSS-linked think-tank Vichar Vinimay Kendra. He has authored two books on RSS. Views expressed are personal.

(Edited by Saikat Niyogi)

Also read: Same family laws for all faiths — what’s Uniform Civil Code, and what courts say about it