New Delhi: It’s often been argued that dividing big, populous states into smaller units helps, from both an administrative and an economic point of view. However, according to a new study, the data doesn’t corroborate such claims about economic benefits.

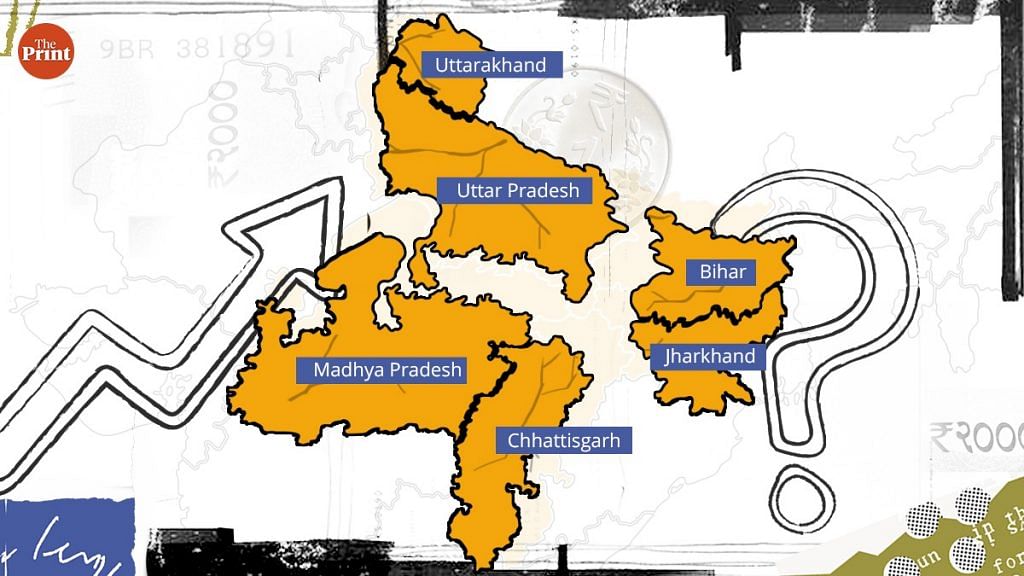

Looking at the impact of the reorganisation of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh in the year 2000, the study found that growth in newly carved-out states doesn’t match the hype, while the “parent” states don’t suffer as much as is generally believed.

The study, titled ‘Does the creation of smaller states lead to higher economic growth? Evidence from state reorganisation in India’, was published by the Mumbai-based Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR), established and funded by the Reserve Bank of India, last week and was authored by Vikash Vaibhav and K.V. Ramaswamy, researchers at the institute.

Though India’s state boundaries have changed several times since Independence, after the year 2000, only five states — Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir — have been reorganised.

The study looked at three of these five states, with the authors excluding Jammu & Kashmir and Andhra Pradesh — both reorganised within the past decade — from their analysis as their methodology requires data from over a longer period.

The study examined the impact of the division of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh on their Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) over three-and-a-half decades (from 1980 to 2015).

It further attempted to find out what impact bifurcation had on the growth of the states both by analysing the post-bifurcation states individually, and by combining the figures for these to get hypothetical numbers for the original, undivided states — as if they had stayed together.

Data for the the three regions that would go on to be carved out as new states in 2000 — Jharkhand from Bihar, Chhattisgarh from Madhya Pradesh and Uttarakhand from Uttar Pradesh — was analysed from 1994 onwards.

Also read: What if Indian states were countries

Bihar-Jharkhand

The study said that, collectively, Bihar’s graph of per capita income (GSDP divided by population) was a flat line during the 1980s and 1990s, which means that prior to its division, the state did not report substantial growth.

It also found that Bihar’s better growth years — taken as a hypothetical combined state, with data from both Jharkhand and post-separation Bihar — started almost five years after it was bifurcated in 2000; till then, it remained flat.

When considering the post-bifurcation states individually, the study found that while Bihar’s growth after separation was stable, Jharkhand initially faced a slump before picking up.

For Jharkhand, the study also found that growth in the region’s per capita income was irregular before it became a state. But due to limited data being available, the authors were unable to comment with certainty about what caused this.

Uttar Pradesh-Uttarakhand

Uttar Pradesh’s trajectory was similar to that of Bihar — flat growth before division and better growth as a hypothetical combined state five years after bifurcation.

When considering the post-bifurcation states individually, the authors’ statistical exercises found no positive impact of reorganisation on Uttar Pradesh. Uttarakhand, on the other hand, performed remarkably after being separated from its parent state.

Madhya Pradesh-Chhattisgarh

In the case of Madhya Pradesh, the growth in per capita income before separation was not as flat as Bihar — it was moving upwards. However, right after its bifurcation, the per capita income of the combined state fell, then picked up.

In terms of the separated states, per capita income fell and stagnated in Madhya Pradesh right after bifurcation. Chhattisgarh, too, initially faced a slump, but recovered quickly compared to MP.

Also read: Kerala’s poor is UP’s rich — how access to basic services varies in Indian states

Analysis

The study points out that even 15 years after bifurcation, the combined states did not exhibit any remarkable differences in economic growth.

“The results from our analysis in this sub-section suggest that the combined states did not show any ‘extraordinary’ positive, or negative, growth in the decade-and-a-half-long period (2000 to 2015) we consider,” it says.

In some cases, the uptick in the growth of per capita income may also accrue to political changes and not necessarily be the impact of reorganisation, say the authors.

“The positive, but statistically insignificant, case of Bihar seems to be on account of the change in political leadership. Was this change in political leadership on account of reorganisation requires further investigation. The case of combined MP is not convincing enough to suggest that there is a negative effect of reorganisation. The case of UP also does not seem to be able to break the mould,” they write.

In isolation, the study finds varying results for the six newly created states, and hence cannot say with certainty that separation leads to economic benefits for all.

In the case of post-separation Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, the growth of the former — the “parent state” — suffered after the separation.

The authors call Uttarakhand an outlier, saying that its growth can be attributed to the sops it offered to industries — whose share in its economy doubled in the decade after it was formed — and the additional funds it received from the central government (the state was given ‘special category’ status).

The authors observe, “We may be safe in concluding that the reorganisation does not affect the parent states as adversely as it was generally believed. Furthermore, the economic growth in the newly created states was nowhere near the hype usually associated with such events.”

Complex dynamics

It’s not that demands for the separation of states into smaller units have ended.

In 2011, Bahujan Samaj Party chief and then Uttar Pradesh chief minister Mayawati passed a resolution to divide the state into four parts.

Over the years, demands for separate states have been raised in various parts of India, such as Saurashtra in Gujarat, Vidarbha in Maharashtra, Bodoland in Assam, Gorkhaland in northern West Bengal.

The IGIDR study aimed to offer policymakers an insight into the economic consequences of the division of states, and said that more research is required to understand the complex dynamics of reorganising them.

“Our analysis captures the average impact in a medium-term, at best. Territorial reorganisation is a complex phenomenon, and it may affect a variety of aspects. There is need for further research to understand these characteristics to gain a more comprehensive picture,” it said.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also read: Prosperous Maharashtra, Karnataka hide a disparity within. Development is not for all: Study