New Delhi: Thousands of Indian students who were studying in Ukraine’s medical colleges are stuck — even if they’ve made it back to India. There simply aren’t enough facilities for them to continue with their medical education back home, which is also the reason why they left in the first place.

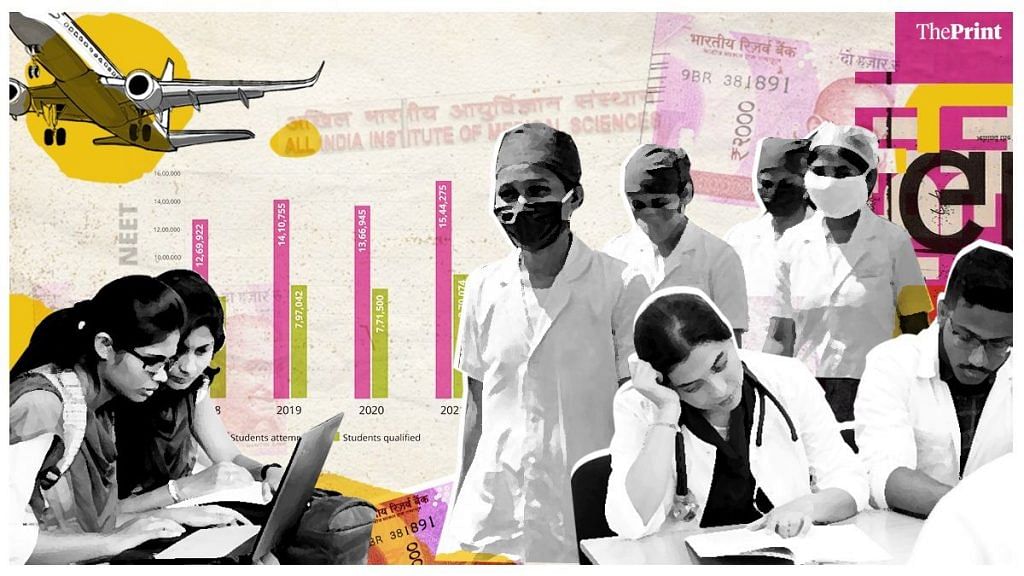

On an average, from 2018 to 2021, 7.8 lakh students in India cleared the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) for admission into a medical college. However, for these 7+ lakh students, there are just 80,000-odd medical college seats, government and private institutions combined, across the country.

Where do these aspirants go? If they have the drive and can afford it, they leave India to chase their medical degree.

Nearly 23,000 Indian students are enrolled to study medicine in China, 18,000 in Ukraine, over 16,000 in Russia, and 15,000 in the Philippines, according to Ministry of Education data.

Behind this exodus is a huge demand-and-supply mismatch for medical seats, which is ironic considering the shortage of doctors in India — just 1 for every 1,511 people.

Unlike candidates for engineering degrees — the other great Indian aspiration — would-be medical students have an extremely limited pool of options. The reasons for this include low health spends as a percentage of GDP, the slow increase in the number of medical colleges, wild variations in fee structures, and the uneven distribution of institutions across the country.

5% acceptance rate, intense competition for govt college seats

India is home to only 562 medical colleges that together can offer 86,649 seats at most currently, according to the National Medical Council (NMC, the erstwhile Medical Council of India).

Ever since NEET came to existence in 2014, medical colleges have on average offered about 50,000-80,000 seats for the MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery) course.

Now compare this to the total number of applicants in the country. NEET press releases show that from 2018 till 2021, 14 lakh students on average take the exam every year. That boils down to an acceptance rate of just 5 per cent for the 80,000 available seats. For comparison, the acceptance rate at the top 100 medical schools in the US (going by US News rankings) is higher at 6.3 per cent, according to Accepted, a California-based consulting agency for college applications.

The competition in India looks even fiercer when price is factored in. For thousands of bright, middle-class aspirants, the real fight is for seats in government colleges, which in 2020 amounted to 42,000 only.

This is because the annual fees in government colleges are relatively affordable— for instance, the prestigious All India Institutes of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) charges only about Rs 5,000 a year, while one of the most expensive, the Goa Medical College in Panaji, has annual fees of just over Rs 1 lakh.

Private institutions, meanwhile, usually demand much higher fees, with some charging as much as Rs 25 lakh per year.

The cut-off for good government colleges in India, however, goes as high as 700 out of 720 marks, and those who score less than 500 marks don’t even stand a chance.

“Almost 50 per cent of the seats available in government colleges go to students in the reserved category. The rest of the students are left with just two options — either appear for the exam next year and get a higher score or go to countries like Russia, Ukraine, and China,” Dr Ravi Sood, dean at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER)-Ram Manohar Lohia (RML) Hospital, said.

“It’s not just those who score 200-300 in NEET who choose to go to foreign countries. Those who score [in the] 90th percentile in NEET are also opting for a foreign degree because they are not able to get admission in the college of their choice,” Dr Sood added.

The Indian government spends 1.35 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on health. This, according to Dr Sood, is where the multi-fold problems in India’s medical education begin.

“When India spends 1 per cent of its GDP on health, how will more colleges open? The problem has to be addressed there first — we need to start spending more on health,” Sood said.

While the number of medical colleges in India has grown significantly over the past decade, this was preceded by a long period of slow growth. Adding to the problem is that institutions are not spread proportionately across the country.

Also Read: Small town India’s aspiring doctors, now trapped in war zone: Why students chose Ukraine

Medical colleges doubled in 10 years, but skewed growth & not enough for demand

Between 2011 and 2021, the number of medical colleges in India almost doubled to 562, from 335.

Statistics from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare reveal that an increase in government colleges led this growth.

In 2011, of the 335 medical colleges in India, 154 were government-run and 181 were private. By 2019-2020, however, there were more government than private medical colleges, with a tally of 279 and 260, respectively (making up a total of 539). In 2021, of the 562 medical colleges, 286 were public and 276 private.

The overall growth rate in medical colleges in India over the last decade is not to be scoffed at, especially when viewed in historical context.

In 1972, India had only 98 medical colleges, which crawled up to a mere 109 in 1981. In the decade that followed, only 19 colleges came up, upping the tally to 128. Things started speeding up from this point on, with 189 medical colleges by 2001 and 314 by 2011.

In terms of average annual growth rate, medical colleges grew by 1.3 per cent per year from 1972 to 1980, 1.8 per cent from 1981 to 1990, 4.43 per cent from 1991 to 2000, and by 5.8 per cent from 2001 to 2010. From 2011 onwards, the average annual growth of medical colleges was 6.68 per cent — the highest in the last five decades.

However, there are way more aspirants than seats. On top of that, state domicile quotas mean that students are often at an advantage or disadvantage due to their geography.

Many states reserve 80 to 85 per cent of their seats for residents. This creates an advantage for students in states that have more medical colleges.

South India — comprising Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, and Puducherry — accounts for about 20 per cent of India’s population, but has 41 per cent of India’s total MBBS seats (33,000 seats across 242 colleges).

Meanwhile, the two most populous states — Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, home to a quarter of the country’s population — have 71 medical colleges offering only 9,168 MBBS seats (just about 11 per cent of the total seats).

According to Dr Rajiv Sood, the “huge shortage” of medical colleges in India stems from the government’s delayed action on adding more institutions.

“For the longest time, the government did not expand the number of medical colleges… it was only the private sector, and that too in South India, that kept on adding more medical colleges,” he added.

The southern advantage

Government and private institutions make up roughly half each of India’s medical college capacity overall. However, the skew in favour of South India is largely attributable to a more rapid growth in the number of private colleges in this part of the country.

From 2009 to 2019, 60.6 per cent of all private medical colleges in India were located in Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Puducherry, according to a 2020 paper published in the peer-reviewed open-source journal BMC Public Health.

The paper noted that this skew might be because private players are motivated to set up in these states because of the “paying capacity of the community” as well as the “availability of sufficient numbers of prospective students”.

Indeed, the per capita income of these states is higher than the average net national income (per capita). According to the RBI’s handbook on the Indian economy, in 2019-20, the average per capita net state domestic product (income) in these states was Rs 2.1 lakh while the all-India average was Rs 1.34 lakh.

Also, according to a study on household expenditure on higher education, conducted by the Mumbai-based Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, South Indians on average spent more than the national average on higher education. Further, “individuals residing in the southern states are more likely to pursue an engineering or medical degree than individuals from the northern states”, the study noted.

Engineering vs medical colleges

Engineering and medicine are the two most desired streams of study in India. However, while engineering colleges have proliferated and witnessed an astronomical growth in the number of seats — well above 20 lakh since 2012-13, according to data from the All India Council for Technical Education — the same hasn’t been true of medical institutions.

The main reason for this, experts say, is the stringent rules and regulations for opening a medical college, as well as the massive resources required, both in terms of money, infrastructure, and, until recently, land.

“Starting a new medical college requires a huge capital investment, which very few people can afford,” a senior official at the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare said.

According to him, setting up a new medical college costs at least Rs 200 crore since it requires a hospital, patient examination facilities, labs, and other equipment. A new engineering college, however, can be established at a starting cost of Rs 15 crore, he added.

“Earlier, the government required at least 10 acres of land for a medical college, but that requirement has been done away in the latest regulations. However, other requirements, like having a 300-bed hospital that’s been operational for over two years, are a hindrance for many,” the official said.

According to the NMC, a medical college can be established either by a state government/Union territory, a university, an autonomous body promoted by the central and state government, or under a statute for the purpose of medical education, a society registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860 (21 of 1860), or corresponding Acts in states, or a public religious or charitable trust registered under the Trust Act.

Until 2008, there was a requirement of 25 acres of land, except in urban areas with a population of 25 lakh or more, for which the land requirement was at least 10 acres.

The NMC has done away with the minimum land requirement from 2021-22 onwards, but the Establishment of Medical College Regulations (Amendment) 2020 rules stipulate that a medical college must be attached to a fully functional hospital with at least 300 beds (except for the northeastern states and hilly areas, where 250 beds make the grade). Such a hospital must be functional for at least two years before a teaching institution can operate.

The rules also add that the teaching hospital and residential area for the students should be in the same complex. “If the campus is housed in more than 1 plot of land, the distance between each one of these plots should be less than 10 km or less than 30 mins travelling time, whichever is lesser,” it adds.

Medical colleges are also more difficult to staff than engineering institutions, the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare official said, since they command a higher pay.

“Medical college faculty who join at the assistant professor level get an initial salary of Rs 1 lakh. Engineering colleges do not have such high pay scales. The faculty members in some colleges start at even Rs 30,000 per month,” he said.

Another health ministry official, who also did not wish to be named, said at least some problems could be solved if medical colleges allowed bigger batches of students.

“We need to increase the number of seats per batch in medical colleges. Currently, no college is allowed to admit more than 250 students in a class. Countries like China have 500 students in a batch… are their doctors of any less quality? They are not! We also need to go for that model,” he said.

According to this official, the NMC’s rolling out of a new qualifying exam for students in their final year of MBBS — expected to be held from 2023 — could solve potential quality problems.

“Now that we have introduced an exit exam for medical students qualifying from Indian colleges, why can’t we admit more students? Their quality can be judged through the exams,” he said.

According to officials in NMC, the rationale for the exit exam is to ensure that doctors brush up their knowledge of the latest procedures and are well-equipped to start practising.

However, some medical experts believe that even if seats are increased, the lack of qualified faculty could throw a spanner in the works.

Lack of qualified faculty

A major issue in the medical education system is the lack of qualified faculty, without which adding more seats would be futile, PGIMER-RML dean Dr Rajiv Sood said.

The NMC guidelines stipulate that there should be 90 faculty members per 100 MBBS students. If an institution is “unable” to provide full-time faculty at this strength, the guidelines add, visiting faculty could help close gaps. “The minimum visiting faculty to be appointed shall be at least 20 per cent of the prescribed faculty for various intakes of MBBS students annually,” the guidelines say.

The ground realities, though, make this easier said than done.

“Currently, there are over 80 per cent vacancies for faculty in medicine, surgery, and obstetrics-gynaecology. Until we have qualified faculty members, we cannot add more seats to medical education,” Dr Sood said.

Professor Shahid Ali Siddiqui, principal and professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College in Aligarh Muslim University, agrees.

“There are vacancies in most of the medical colleges in India and that directly affects the intake of students. Per the NMC guidelines, the number of students who can be admitted will depend on the faculty members, hence the larger the faculty shortage, the bigger the seat shortage,” Dr Siddiqui said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: What forced Naveen to study medicine in Ukraine — reservation or NEET? Here’s the real answer