Bahraich/Balrampur/Shravasti: Shiv Kumari, 36, says she lives with crushing guilt every day. About three years ago, she convinced her husband Bikesh Rana to quit his low-paying construction job at their village in Shravasti district of Uttar Pradesh and head out to Uttarakhand for better work, while she stayed back with their three children.

“He never wanted to leave despite so many men from our village working outside. It was I who kept pushing him to go and earn more so that we have a decent life,” Shiv Kumari says quietly, her hands busy making small leaf plates.

At first, the move had worked out well. Rana made good money in the neighbouring state, working at the Tapovan-Vishnugad hydel project of the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) in Chamoli district. Where he once made barely Rs 250 to 300 a day, he was now sending home Rs 15,000 regularly. “Finally, I was able to save some money after meeting the house expenses,” Shiv Kumari says.

The separation was hard but many families, most belonging to the Tharu tribe, like Rana, were in the same boat. Their village in Sirsiya block of Shravasti, in fact, has barely any young men at all, since most have migrated for better work, including to the hydel project in Uttarakhand.

Then, disaster struck. On 7 February 2021, a portion of the Nanda Devi glacier broke off in Chamoli, leading to an avalanche and flooding in the Alaknanda River. At least 15 people died and scores went missing, many of them labourers at the Tapovan hydel project site.

Bikesh Rana was one of the dead. Four other men from his village also lost their lives in the deluge.

Shiv Kumari has received a Rs 20 lakh cheque from the NTPC, but she is still worried about how she will support herself, her three children, and her mother-in-law. “With five mouths to feed and no earning member, how long will it last?” she asks.

Her neighbour, Sita Rana, is in a similar predicament. She lost her 19-year-old son to the Uttarakhand disaster and also suffers from guilt. “I feel so guilty all the time that I forced him to go. But there is no work in the village. If there was, would so many young men move out?” she says.

While the deaths of these labourers were due to an unforeseen disaster, it underscores the precariousness of migrants’ existence and the helplessness of their families back home, who have little to rely on other than handouts, which may or may not come.

Yet, across Uttar Pradesh’s three most backward districts — Shravasti, Bahraich, and Balrampur — which are rank 1st, 2nd and 4th across India in government think-tank NITI Aayog’s Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index (MDI), migration is often necessary for survival.

Also Read: Can’t learn, can’t work, can’t even cross river: Life in 3 of India’s 4 poorest districts, all in UP

Destination: Anywhere but here

For most youth of Shravasti, Bahraich and Balrampur, hope is always elsewhere.

From Mumbai to Pune, Delhi to Ludhiana, Chamoli to Srinagar, Surat to Hyderabad, Jaipur to Gurugram, these young men are willing to go wherever they learn there is work for them, usually through other migrants — their friends, cousins, erstwhile neighbours.

Many prepare for the inevitable departure before they reach adulthood and drop out of school if an opportunity arises. It seems worth it to them and their families alike: In the village they might earn Rs 7,000-8,000 a month, but jobs in cities can bring them pay packets of Rs 15,000-25,000 on average.

While the metro projects, malls, and hotels of the big cities draw many workers, many also shift to smaller towns in other states.

Manish Kumar, 22, a resident of Bahraich’s Gulalpurwa village, is getting ready to leave for Surat to work in a thread-making company.

“My cousin is working in a thread company. He said he will get me a job there. He gets Rs 10,500 for working eight hours. If he works overtime for 12 hours, he gets Rs 15,000,” Kumar says.

Having his relatives around has made him more confident about the move. “I will manage to save more because we will share expenses for food and lodging. Besides, in a new city, I will have somebody to talk to.”

There are instances galore like this — brothers, cousins, neighbours sharing expenses to save and send home more money.

‘It’s a money order economy’

Migration from UP’s villages to cities is like a “chain link”, according to Dr Prashant Kumar Trivedi, associate professor of sociological studies, Giri Institute of Development Studies, Lucknow. “One person goes looking for a job in the city. Once he gets one, others from his village use the link to go there,” Trivedi says.

“It’s a money order economy in villages across the region. Though no government figures are available, our research shows that in some villages, the migration is as high as 70 per cent,” he adds.

The 2011 Census puts the total number of inter-state migrants in India at 5.4 crore. Of all the states, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar were the largest source of such migrants while Maharashtra and Delhi were the largest receivers. Approximately 83 lakh residents of Uttar Pradesh had moved to other states, either temporarily or permanently, according to the 2011 Census. These numbers would have increased manifold by now.

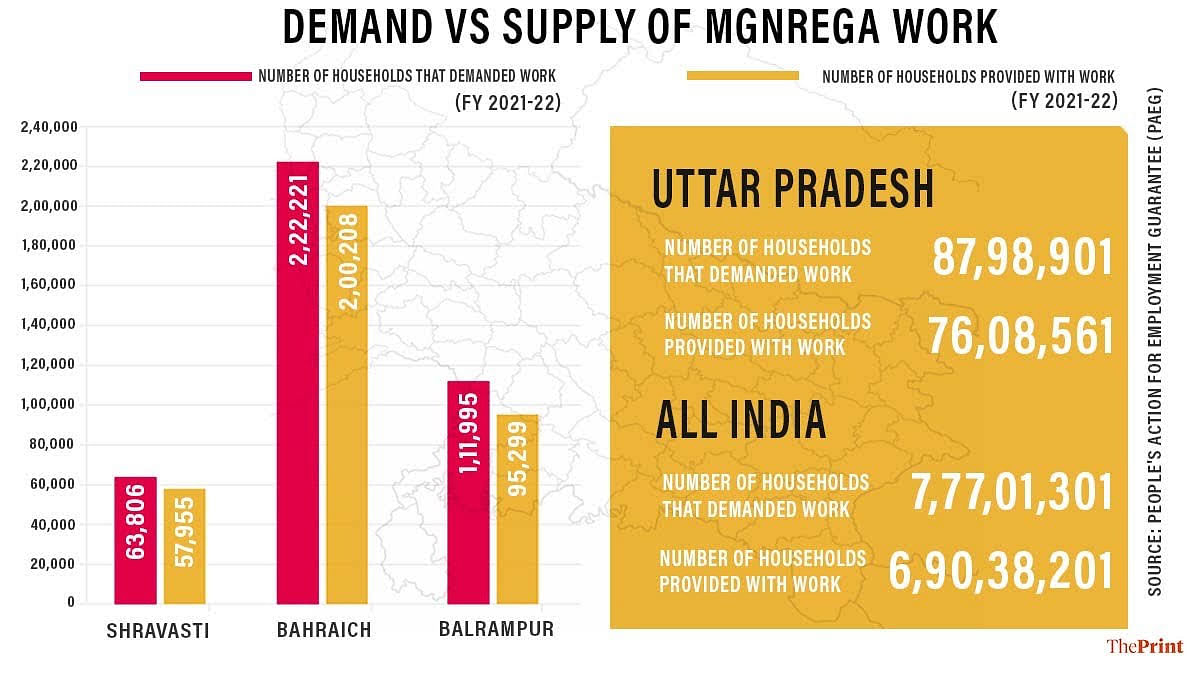

That migration continues to rise despite schemes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), the central government’s job guarantee programme, indicates a massive demand-supply mismatch, says Anuj Goyal of the People’s Action for Employment Guarantee, an activist group.

“There is large-scale unemployment to begin with. The fact that people are coming to get jobs under MGNREGA is an indication. Data shows that the extent of employment provided is less than the employment demanded. We have come across many instances where the demand for jobs is not even recorded,” Goyal says.

Work, skilled or unskilled, is hard to come by in villages, where agriculture is the mainstay. The majority of the poor have small landholdings that are not enough to sustain large families.

Even a MGNREGA job fetches just Rs 201 per day in Uttar Pradesh, which is less than in any other state. In Karnataka, for instance, the minimum wage for a MGNREGA worker is Rs 441 per day. In Haryana, it is Rs 377 and in Punjab Rs 369.

The situation is no better in urban areas. Government jobs are few and far between while the private sector’s presence is almost negligible.

The “cycle of migration” will likely continue unless there are efforts to set up more industries and factories in Uttar Pradesh, believes Chittaranjan Senapati, an associate professor at the Giri Institute of Development Studies in Lucknow, whose research has focused on skill development and employability in UP.

“The government will have to invest in setting up industries locally. You can then skill people accordingly,” he says.

However, Senapati adds that skills training in itself, such as at the various Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), does not make people automatically employable.

“The youth are trained in courses for which there is no demand locally. This forces even the educated youth to migrate. This defeats the very purpose of setting up these ITIs. There may be more enrolments at these institutes, but that’s it,” he says.

Also Read: Unemployment and unlimited data pack — UP’s youth are neither angry nor idle

Entrepreneurship when all else fails

Even as droves of young men exit their villages, a few are trying to change their lives by opening up small businesses, with bike repair shops and mobile kiosks being the most popular options.

Lucky Singh, 18, got some help from his father to open a small roadside bike repair shop at Lakshman Matehi village in Bahraich’s Balaha block. On a good day, he earns about Rs 400-500.

The market is slow but the election season is helping him, he adds. “Whatever I am earning these days is because of the elections. With netas campaigning and political rallies happening, I get a steady flow of customers.”

Singh says he does not regret his decision to stay back. “At least I don’t have to work for anybody else. My three elder brothers are working as cooks in Mumbai and Aurangabad. It’s a tough life. They don’t save much after paying rent and meeting their family expenses. My old parents, grandmother, and sister are here. I look after them,” he says.

Singh, who has studied till Class 7, says he decided to go into business after trying and failing to get work under MGRNEGA.

“The pradhan (headman) was doing mischief. Every time I went asking for a job, he would come up with some or the other reason and shoo me away. I got fed up,” he says.

The mandate of the MGNREGA is to provide at least 100 days of guaranteed wage employment in a financial year to every rural household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work. The gram panchayat (village council) headed by the pradhan not only receives applications for work, but is also responsible for issuing job cards.

However, across all three districts, many people complain about pradhans obstructing villagers from getting jobs through MGNREGA unless a bribe is paid.

The local administrations and pradhans deny these allegations, but anecdotes about corruption abound.

“The daily wage under MGNREGA here is Rs 201. Out of this if I have to give a certain percentage to the pradhan, what will be left?” asks Tauhid Ahmad, a resident of Bahraich’s Dularpur village, who is in his 20s.

Like Lucky Singh, he too has set up a small business. His small shop sells mobile chargers, phone covers, and some stationery items and helps him support his mother and two sisters, with whom he lives.

However, Covid has slowed things down. “People are not spending. If I don’t get customers, where will money come from?” he asks.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Code red on malnutrition: Why half the kids in 3 poorest UP districts are stunted, many ‘wasted’