Ryngksan, East Jaintia Hills: In this part of East Jaintia Hills, Meghalaya, the dwindling of hope looks like rice cooked on a slow simmering flame — tea waiting to come to a boil, lunch served at half-past noon and uniforms drying on a clothesline.

At the Ksan coal quarry, where 15 men were submerged alive when an illegal ‘rat-hole’ mine was flooded nearly two months ago, over 100 rescue personnel are waiting for something to happen — but for weeks, nothing has.

Santosh Kumar Singh, the assistant commandant of the National Disaster Relief Force (NDRF), has been living at a Jaintia cement factory guest house roughly 20 km away from the site, for nearly two months now. He is among 70 NDRF officials performing scattered roles.

On some nights, when the hope of discovery resurrects itself, he also stays in a small 3x3m thatched-roof hut that once served as living quarters for the unauthorised labour working the mines.

Of all the officers present, he is one of the select few to miss both Christmas and New Year with his family back home in Guwahati.

“The NDRF unit in Guwahati mostly comes from a BSF background, so even our families are used to it now,” Singh tells ThePrint. “But here, it’s been going on for a long time, and we still don’t know much longer the operation will continue.

“This is perhaps the longest rescue operation in NDRF’s (Guwahati) history,” he adds.

Also read: Navy divers spot another body of the trapped miners in Meghalaya coal mine

Coming together

But it’s not only the NDRF that’s biding time at Ksan.

With 10 specialised divers from the Indian Navy, a contingent of nearly 15 Army officers, three medical technicians on daily call, 15 members of the State Disaster Response Force (SDRF) and a cameo by a 22-member team from the Odisha Fire Services, the Meghalaya mine rescue mission has become one of the largest experiments in civic co-operation till date.

Coal India Limited (CIL), Kirloskar Brothers and KSB have also provided high-powered pumps to help empty the flooded mine of water.

Despite all the seeming ingredients for a successful mission, including national media spotlight, there has been little to show — only the body of 30-year-old Amir Hussain from Assam’s Chirang district has been recovered almost 60 days since the tragedy occurred on 13 December.

“Nearly 20 crore litres of water have been pumped out since the beginning,” said a senior official at the site. “And the water level is still almost exactly the same.”

The officials on site remain stoic in the face of repeated failure, many of them citing “a sense of duty,” and “following orders” as the guiding principles behind what appears to be an otherwise doomed exercise.

As of 4 February, even Justice A.K. Sikri of the Supreme Court “seems to be certain that nobody is alive” — a far cry from the top court’s 11 January order to continue the operation because “miracles do happen”.

And yet, the Supreme Court is holding forth — blaming the mine owner for the tragedy Friday and asking for a notice to be issued in his name. The next hearing is scheduled for 22 February, meaning that at least till then, Singh will not get to go home.

“Someone has to call it,” additional superintendent of police, East Jaintia Hills, Lethindra Sangma tells ThePrint. “But as of now no such directive has been issued and the operation is continuing.”

In this backdrop, East Jaintia Hills deputy commissioner Frederick M. Dopth is also busy preparing for the upcoming district council elections in Meghalaya. When ThePrint contacted him for a comment, he said: “Elections are coming, please contact my DPRO (deputy public relations officer) at the spot.”

DPRO R. Susngi, however, told ThePrint that he “is no longer officially a spokesperson for the mission, and that the responsibility has passed to the secretary of the political department”.

Also read: Several skeletons found in Meghalaya’s illegal rat-hole mine 35 days after tragedy

A day in the life

Between an early breakfast, lunch and dinner at 7:30 pm, tea is served at 10 am and 3 pm in the camp set up by the 14 Assam regiment of the Indian Army a week ago.

Over 10 large tents, with a capacity to accommodate 10 people each, have saved the Navy divers precious hours in transit by allowing them to stay overnight on-site.

Subedar Umesh Sunar says he “does not know when this will end, but we are here till whenever the Navy is”.

In moments of vacancy, Sunar says that the men play games like volleyball.

A few hours earlier, a young Navy officer, not more than 28 years old and a native of Rohtak in Haryana, walks past the civil police check-post at the rescue site with music playing from the loudspeakers of his phone. He greets Singh, laughs and says “aaj toh khali haat baithe hai (Today we’re sitting with nothing to do).”

As of now, Ksan can be defined by the five NDRF officers geared up in fluorescent orange suits, who, after having conducted the prerequisite tests on their oxygen tanks, are on “active standby” — waiting and ready for the moment that the Indian Navy’s Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) will detect the presence of another body.

Octopaul Phawa, the SDRF official in charge of the stock-room at Ksan, says that four large sacks of rice, three of pulses, and 40 kg of sugar, usually lasts those staying next to the pit for a week. Fifteen boxes of water, three boxes of milk and 25 kg of vegetables are also brought daily.

His colleague, Phyrnai Lang Marwein, says that he “has never been a part of an operation like this before”.

The SDRF has largely been relegated to non-tactical assistance roles. “This is an underwater rescue operation, which is not our area of expertise,” Marwein says. “If it was a surface level disaster, then we could have participated more.”

Doctor N.P. Suchiang, the head of a hospital in Khliehriat, is spending Rs 1,000 a day on fuel to reach the site from the district headquarters. She, along with a host of other doctors and nurses on rotation, has been treating the stationed officers for “minor gastritis, skin problems, colds and allergies”.

She says that “if the divers aren’t diving that day, then there’s no point staying till late, because we have to leave our other responsibilities and patients to come here”.

Pump generators continue to hum in the background of this silent wait — at a cost being borne by the district administration.

Also read: NGT panel blames ‘un-abetted illegal mining’ for Meghalaya tragedy

A failed mission from the start

There are a lot more incongruent pieces to the puzzle than slow response time and a lack of equipment.

According to an official at the site, the complete absence of a rat-mine blueprint, owing to the illegal nature of the entire enterprise, means that the authorities had to go in blind — even the exact number of labourers trapped in the collapsed pit could not be ascertained till four days after the tragedy.

The Navy’s ROV, designed with claws in the front, was never built for the purpose of extracting bodies.

“The coal dust on the inside of the rat tunnels gets mixed with the water when the ROV turbines spin, which in turns makes the water cloudy,” Ranvijay Singh, an NDRF officer, explains to ThePrint. “This means that the cameras can’t see anything at all. But it’s only through the ROVs that we’ve had any success.”

The remote location of the pit — about 45 kilometres away from the district administration headquarters — means that the availability of resources was both scarce and delayed. Basic necessities like potable water are difficult to come by in the area, thus requiring numerous trips to and from nearby villages and marketplaces.

Most of all, the force of nature remains unbeaten — water from the Lytien river continues to gush into the mine faster than it can be removed by the most powerful pumps available.

The hope of reducing the water level has more or less been abandoned in principle, and yet in practice, R. Susngi, despite being relieved from his duties as DPRO as he says, continues to send updates on an ‘Operation Ksan’ media WhatsApp group pertaining to the lakhs of litres discharged every day.

Also read: These are the 15 Meghalaya miners trapped in a rat-hole coal mine

Those left behind

But Ksan is more than just a tactical operation. Just and Rita Dhakr, the mothers of three local boys from the nearby Lumthari village, are still waiting for the bodies of their sons to come back home.

Sitting on the front-porch of their house, surrounded by their remaining young children, they say that “if we get the body, at least we’ll be able to bury it”.

Just, who lost Long, 22, and Nilam, 20, to illegal coal mining, remembers her sons as “hard-working boys who concentrated on earning for the rest of the family”.

“They would spend their off days foraging for wild vegetables in the forest because they loved to eat those,” she says. “During work season, they would find jobs tiling farmland, cutting wood or as local labourers for projects.”

As of now, Rita and Just say that not a single MLA or district official has come to visit the family, who are struggling to gather sufficient food after the loss of the only earning members at home.

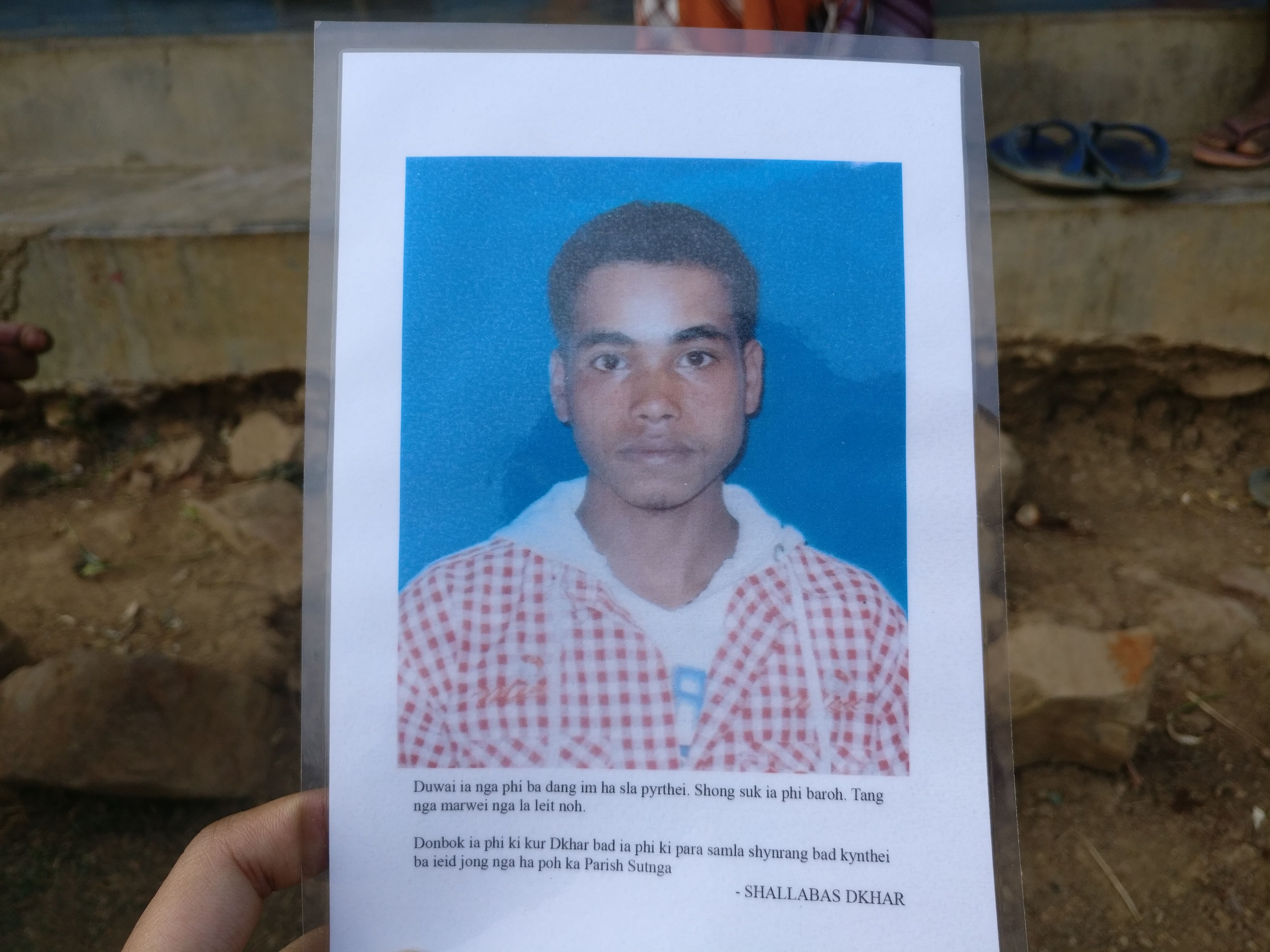

Rita, who lost her son Shallabas, holds his baby brother in her arms. Shallabas leaves behind four sisters and two brothers.

When a body was spotted by the ROV on 16 January, all efforts to retrieve it had to be abandoned, because “in the process of pulling out the body, the skull, the left wrist, and the leg from the knee-level got disengaged,” read the Meghalaya government’s status report as presented before the Supreme Court at the time.

No compensation has been given by the state government either, although Aldous Mawlong, secretary, Meghalaya Human Rights Commission (MHRC), tells ThePrint that the mining department is set to submit a report to them in a week’s time.

“If you’re saying that the rescue operation should be called off because it’s costing too much money and man-power, then you’re saying that the price of human life is cheap,” social activist Angela Rangad told ThePrint.

“Illegal coal mining has taken the lives of so many people in Meghalaya. We need to fix accountability, and that begins by highlighting that it has been going on unchecked and with political patronage,” she adds.